How Are We Getting Phished?

Table of Contents

Introduction

Over the past 10 years of my 20-year cybersecurity career—primarily within Turkey’s leading banks and IT subsidiaries—I’ve taken on leadership and executive roles, including CISO, thanks to the knowledge, experience, and achievements I’ve gained. While the winds have carried me into executive leadership roles in recent years, I’ve continued to stay passionately connected to the technical side of cybersecurity, which has fascinated me since the age of 13. I continue to conduct security research, and thanks to working at a security vendor like SOCRadar, I strive to benefit from the vast pool of data like our customers do, and to share what I learn with you to raise awareness.

I Got an Idea!

One day, while browsing the SOCRadar Extended Threat Intelligence platform, I noticed a significant increase in phishing sites specifically created to impersonate prominent corporate brands in Turkey.

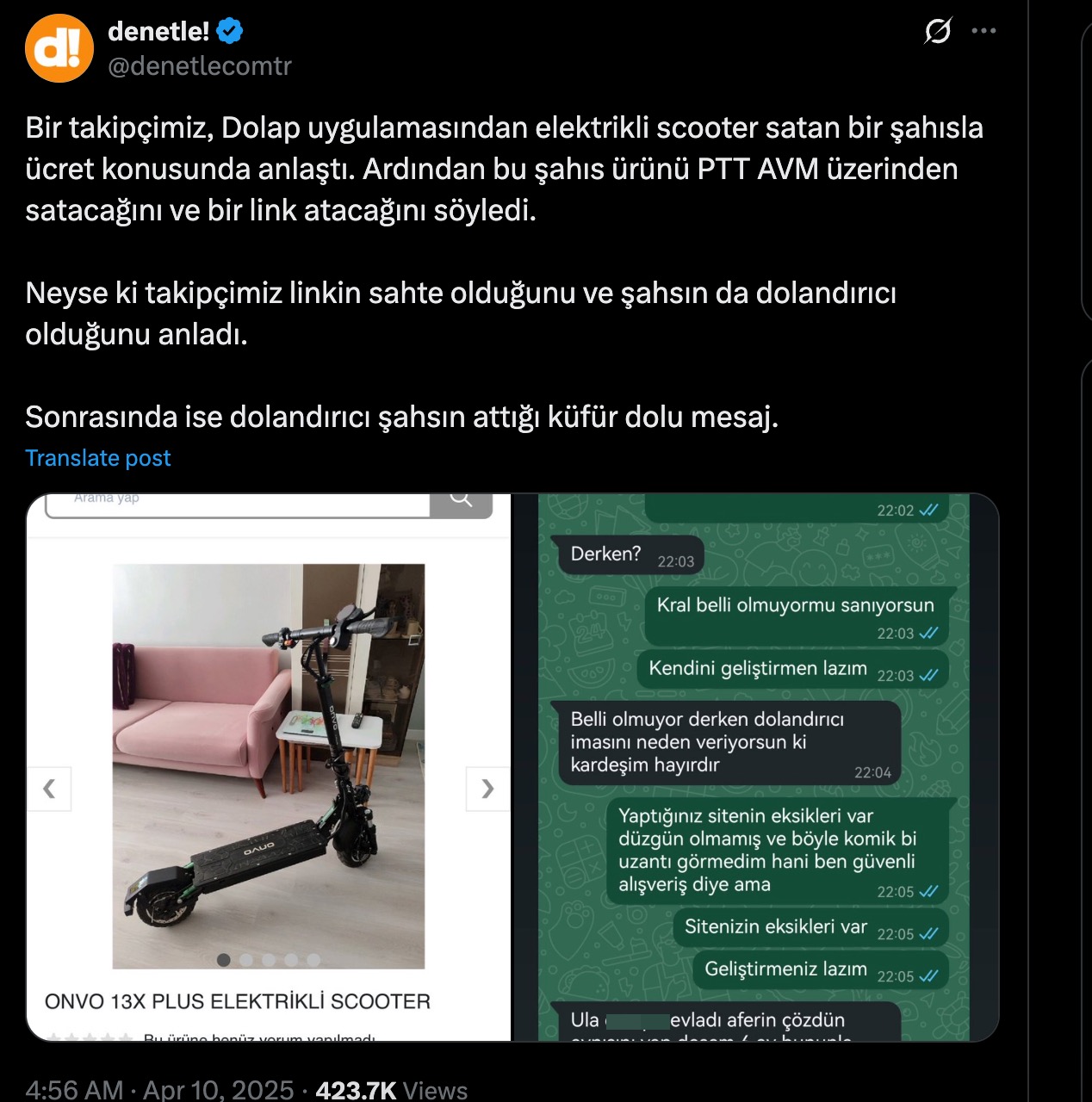

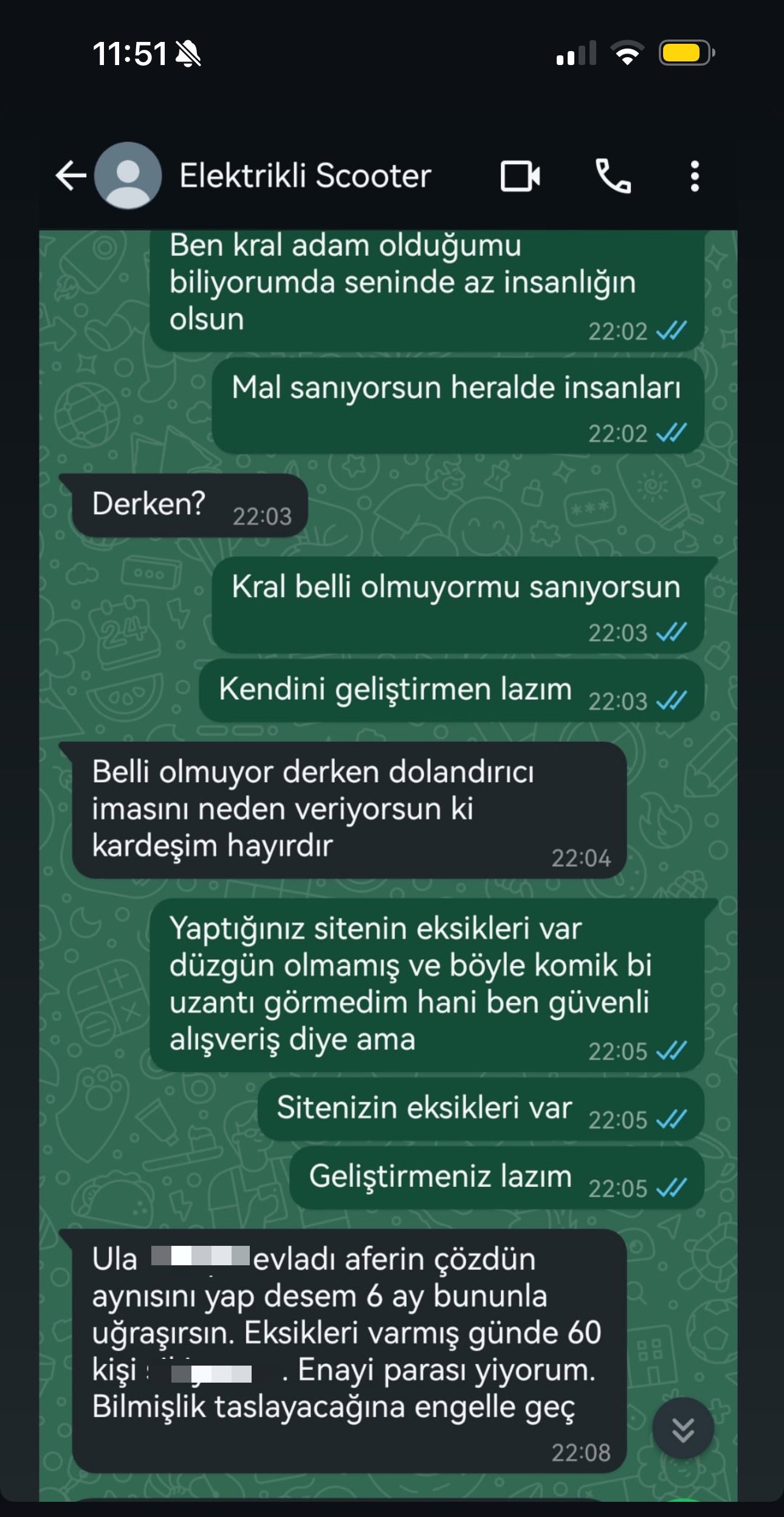

Recalling posts from victims who were scammed on social networks like LinkedIn and X (formerly Twitter), I decided to conduct a security investigation into how we get phished by scammers—and to share my findings as a series of blog posts.

In the example above, a brazen scammer shamelessly boasted about scamming 60 people a day by impersonating the e-commerce platform PttAVM.com.

Source: denetle!

Cogito, Ergo Sum!

When I started thinking about answering the question “How?”, I quickly realized that simply collecting a bulk list of phishing sites wouldn’t be enough. That’s because, without having screenshots of each one, identifying which corporate brand a scam site is impersonating—or what kind of information it’s trying to steal—might be theoretically possible using tools like urlscan.io, but in practice, it would be time-consuming and inefficient.

So, to speed things up and make the process easier, I decided to leverage SOCRadar’s Threat Intelligence data pool, along with the National Cyber Incident Response Center of Turkey (USOM) and their publicly available list of malicious URLs.

“Write This Down” — One Python Script, Please

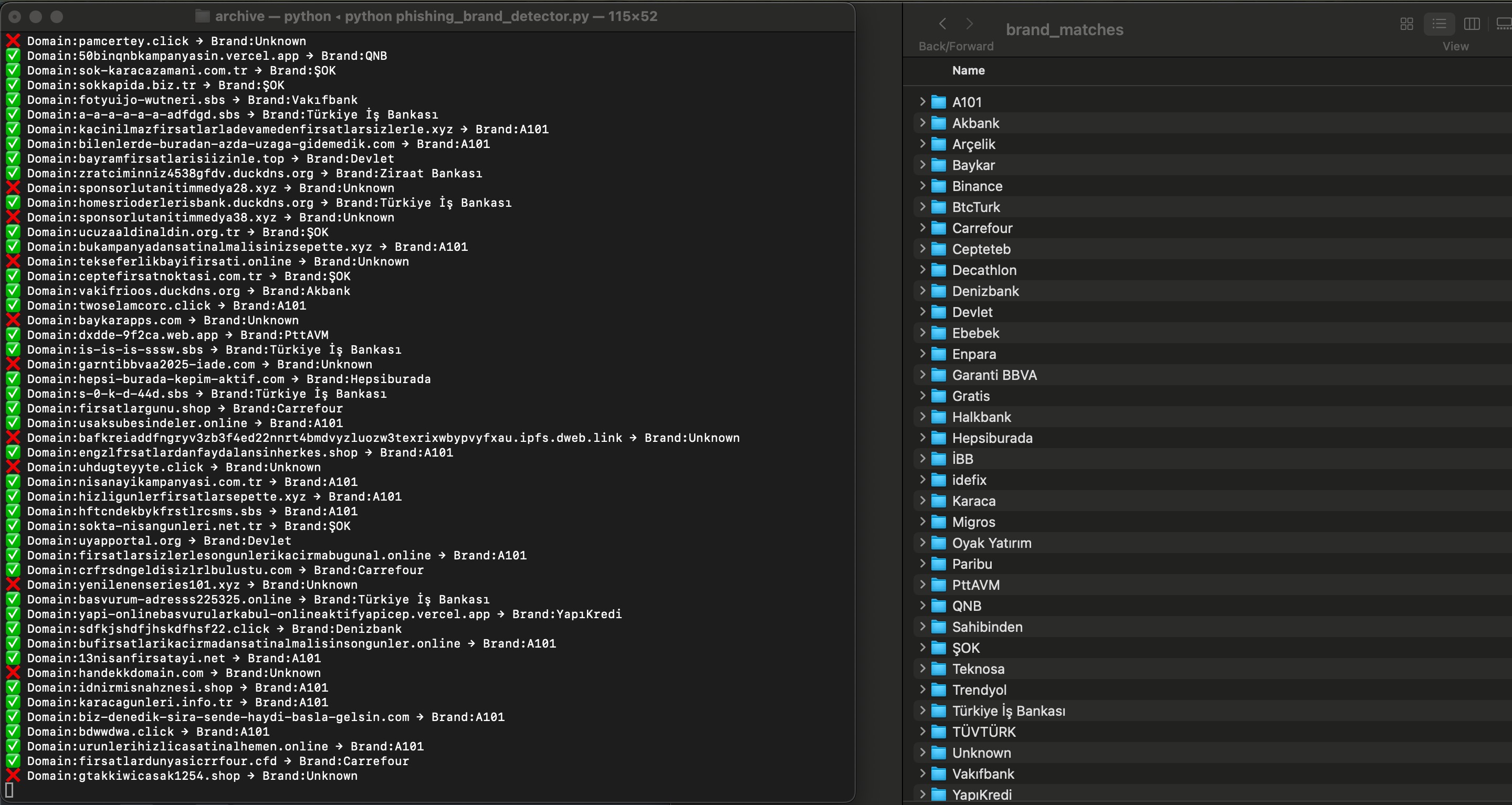

From SOCRadar’s data pool, I gathered 5,000 phishing domains detected in the first four months of 2025. To ensure transparency and verifiability, I focused only on domains that overlapped with Turkey’s USOM Malicious URL list and still had active websites. I also collected their screenshots.

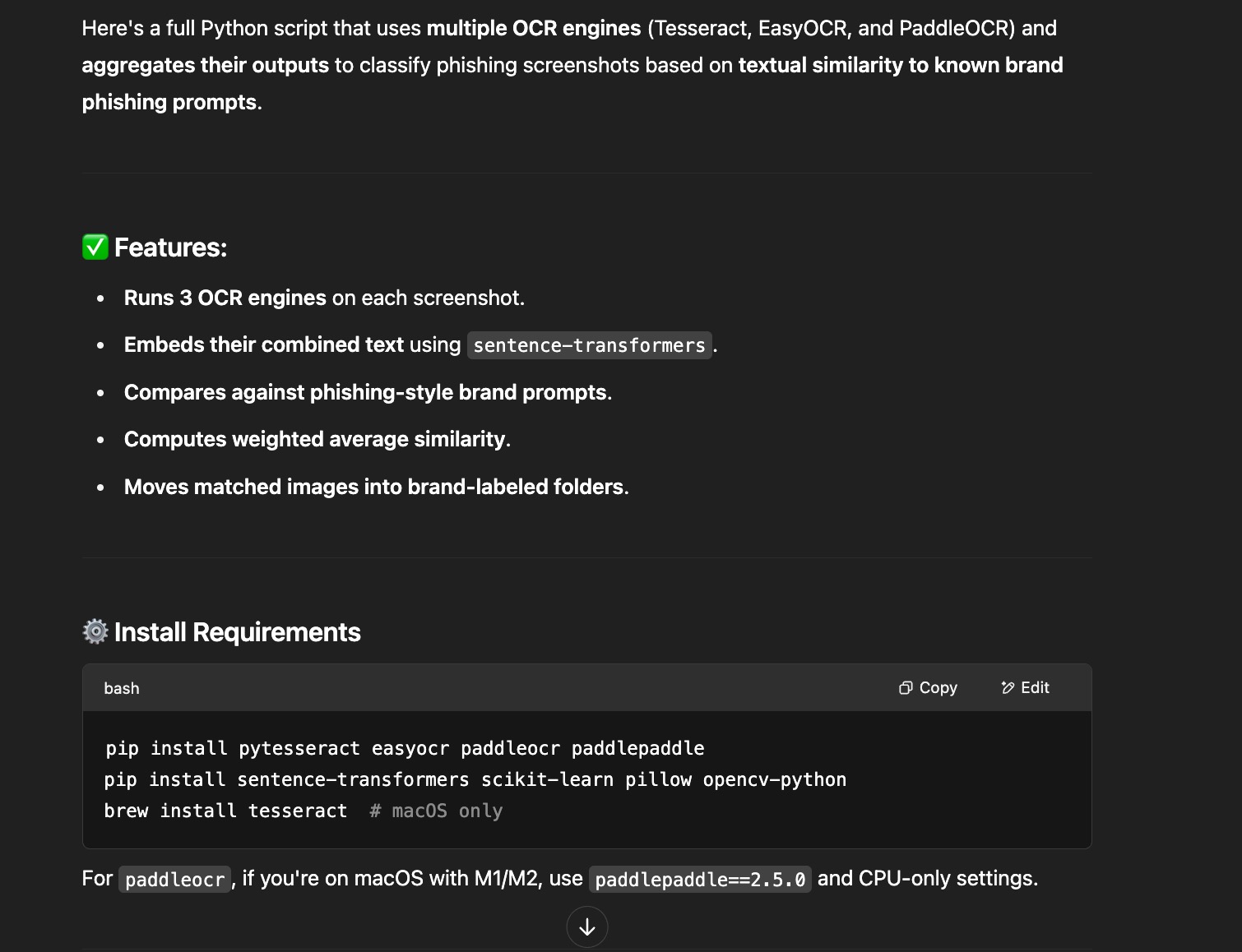

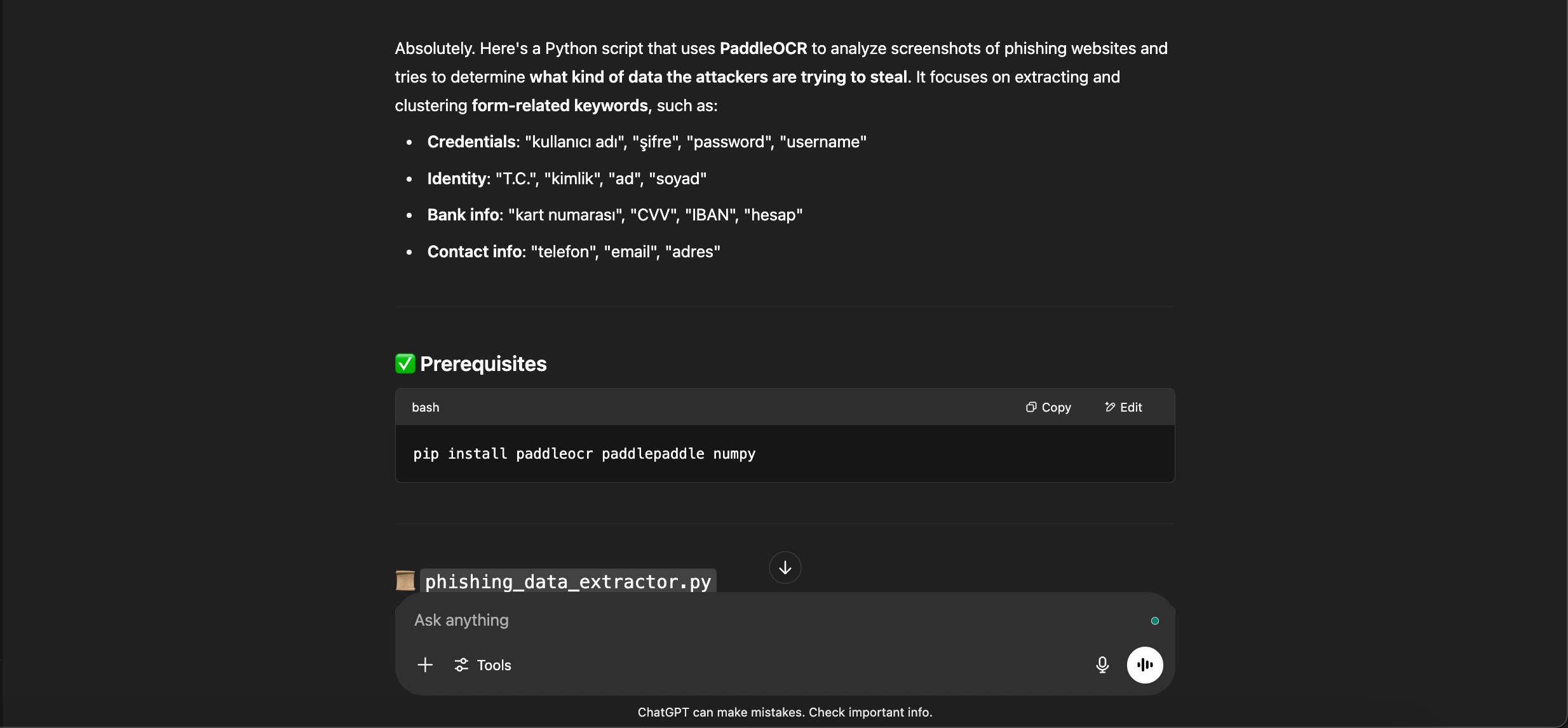

The next challenge was identifying which corporate brands these scammers were impersonating or abusing in those screenshots. For that, I needed a Python script. But this time, instead of writing the code myself like I did in the past, I decided to ask one of the AIs that’s supposedly “going to take all our jobs” to do it for me: ChatGPT. :)

Based on my past experience, I knew the cleanest way to tackle this was through OCR analysis, so I guided ChatGPT accordingly—and had it generate the Python script for me.

Just a few years ago, getting a value-added tool like this built in minutes—and for free—through a few simple prompts to ChatGPT would have sounded like something out of a sci-fi movie. And yet, here we are, making it a reality in this very post.

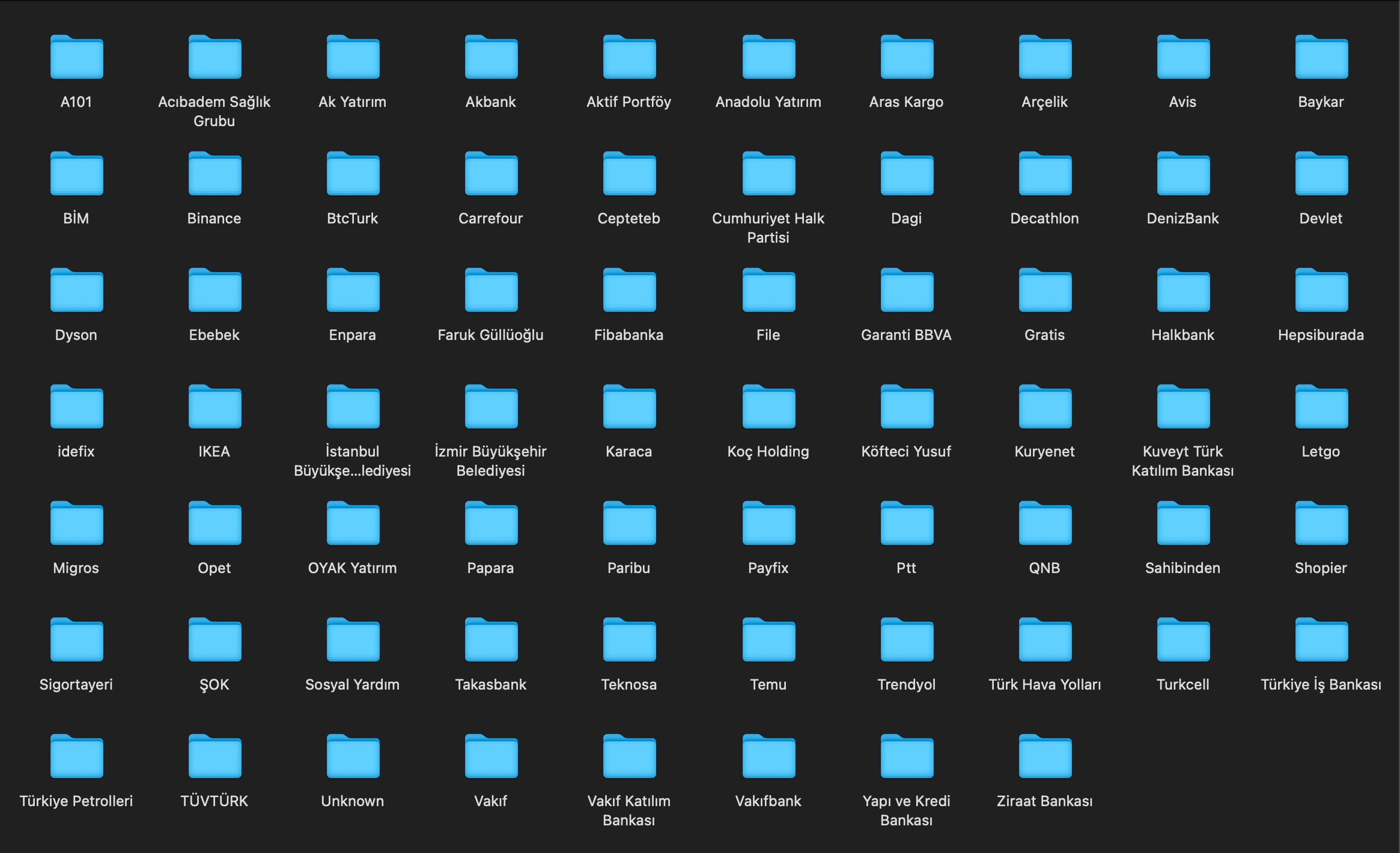

After running the tool I named Phishing Brand Detector, which analyzes screenshots of phishing sites and identifies the impersonated corporate brands, I excluded government, foundation, and social aid websites from the dataset. What remained revealed that these phishing sites targeted a total of 65 different corporate brands.

In the first version of this tool generated by ChatGPT, there were 173 false positives—a 3.46% false positive rate. After a few rounds of refinement, I managed to reduce that number to 91 false positives, or 1.82% in the final version.

According to cybersecurity industry standards, a false positive (FP) rate below 1% is ideal for automated actions like blocking. Rates between 1%–5% are generally acceptable for cases reviewed by human analysts.

Those familiar with SOCRadar might say, “You basically got ChatGPT to recreate SOCRadar’s Brand Protection module—and it worked!” But with a dataset of just 5,000 offline examples and a 1.82% FP rate, it’s a bit premature to say that.

What really matters is the ability to detect a phishing domain shortly after it’s registered and goes live, identify the brand being impersonated within minutes, and trigger an alert. The day we can get ChatGPT to write a tool that can detect 109,709 phishing sites in four months—like SOCRadar does—and keep the false positive rate under 1%, that’s when we’ll know we’ve really nailed it. :)

Which Sectors and Brands Are Being Targeted?

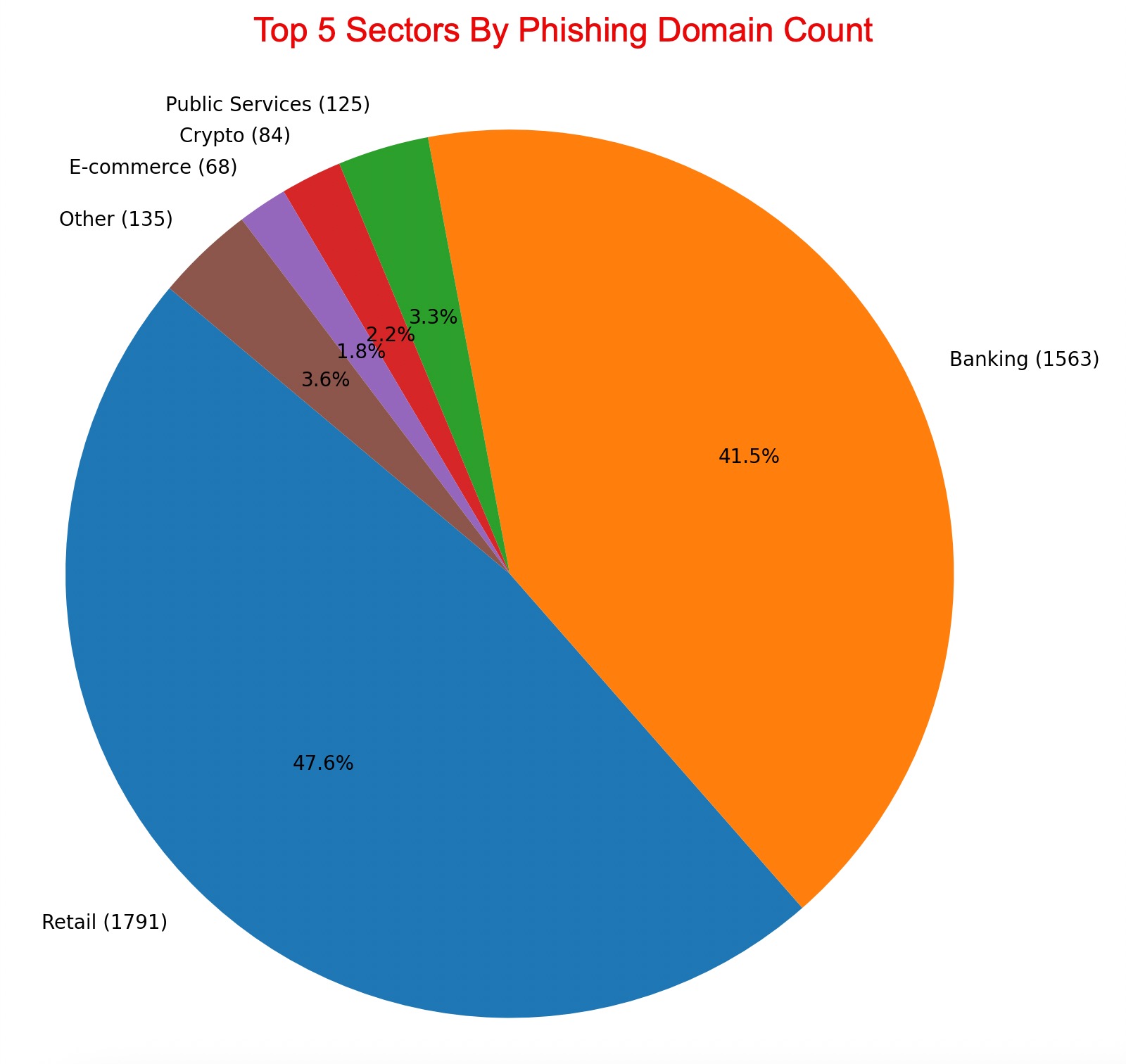

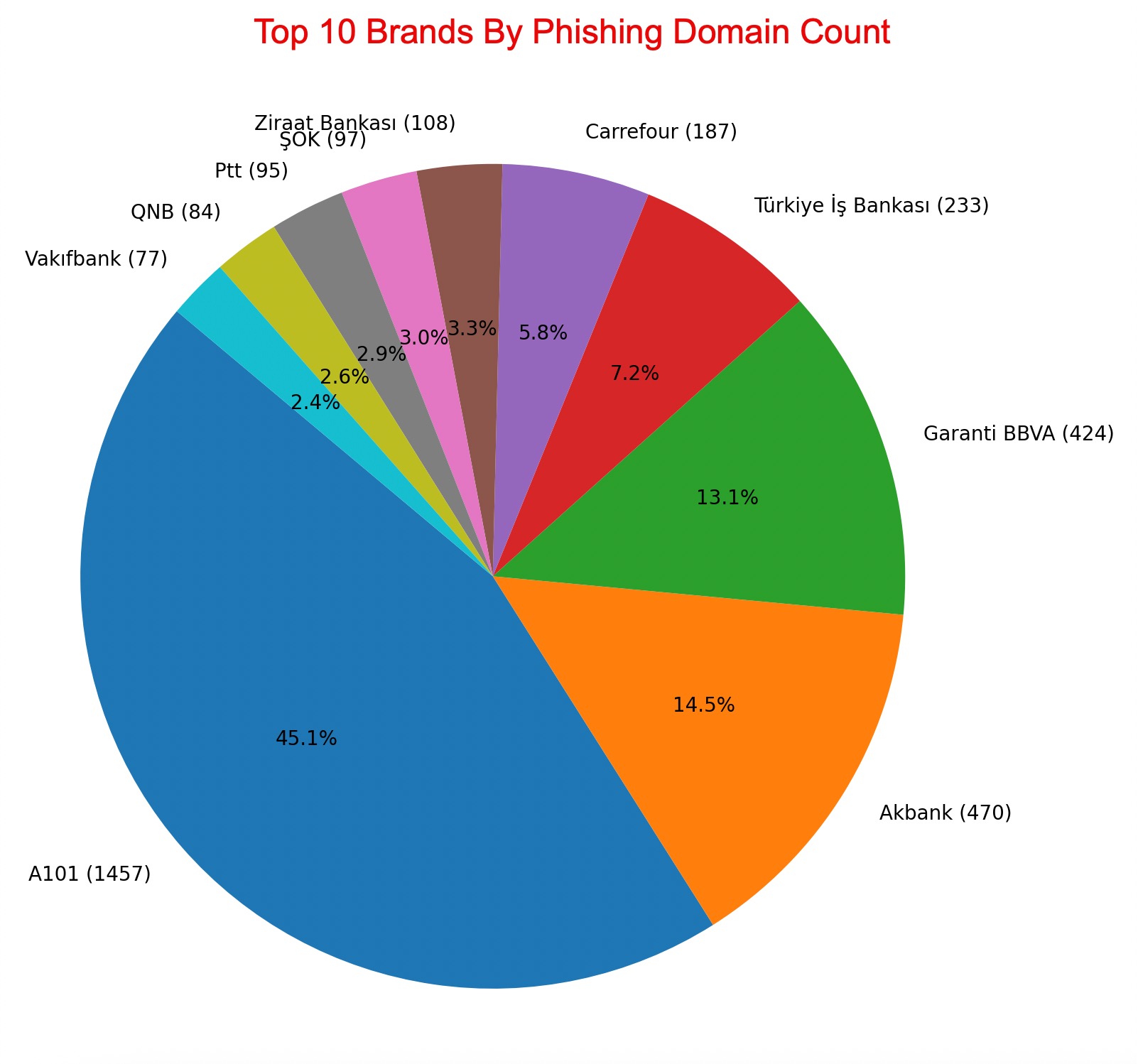

If we had taken a poll beforehand, most—including myself—would have probably guessed that banking would top the list of most targeted sectors. Surprisingly, the numbers told a different story: the retail sector came out on top, followed by banking.

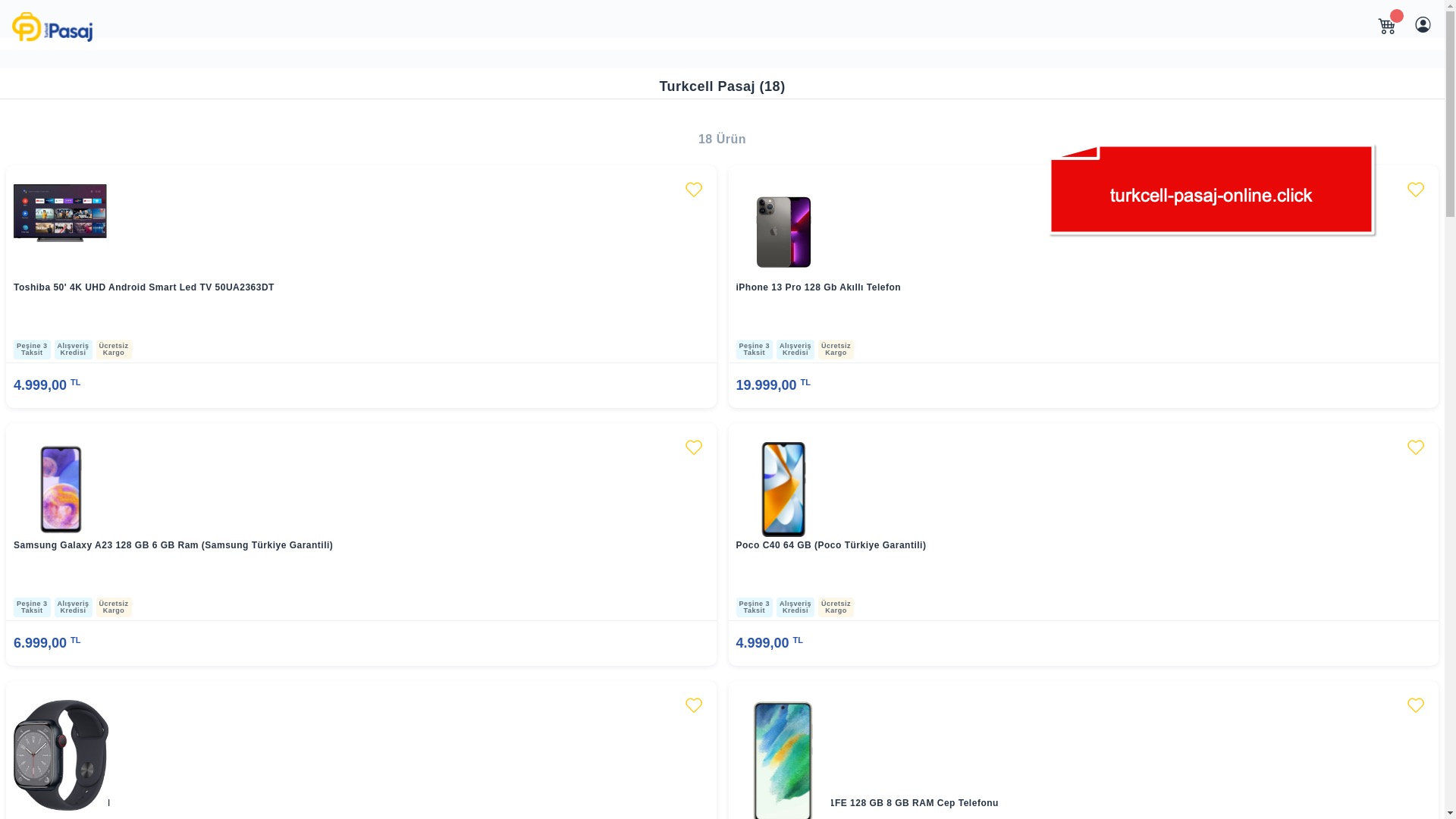

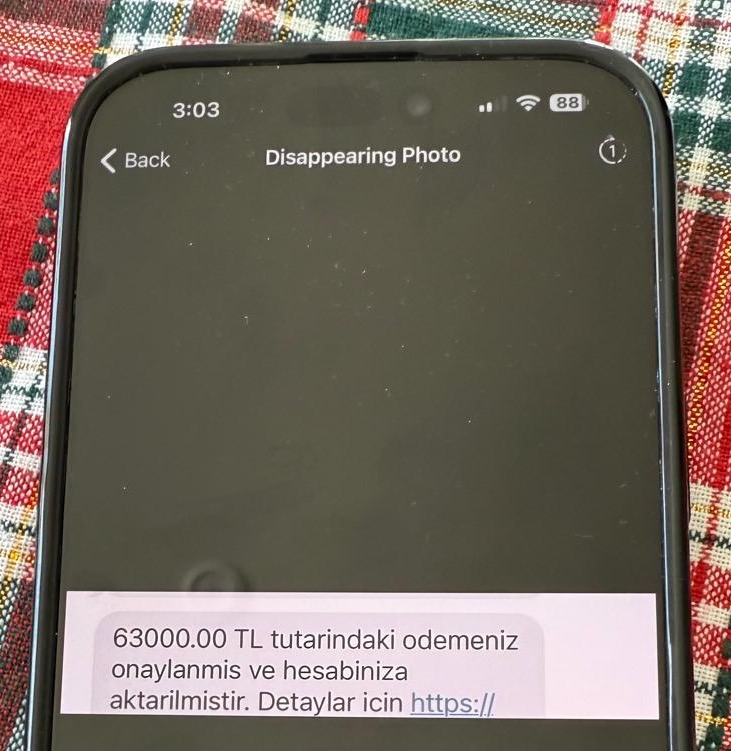

On second thought, retail taking the lead shouldn’t be that surprising. After all, when an Apple iPhone 13 512 GB—with a market price of 63,429 TL—is advertised at 24,990 TL, it’s easy to see how careless users might fall for the bait.

How Are We Getting Phished?

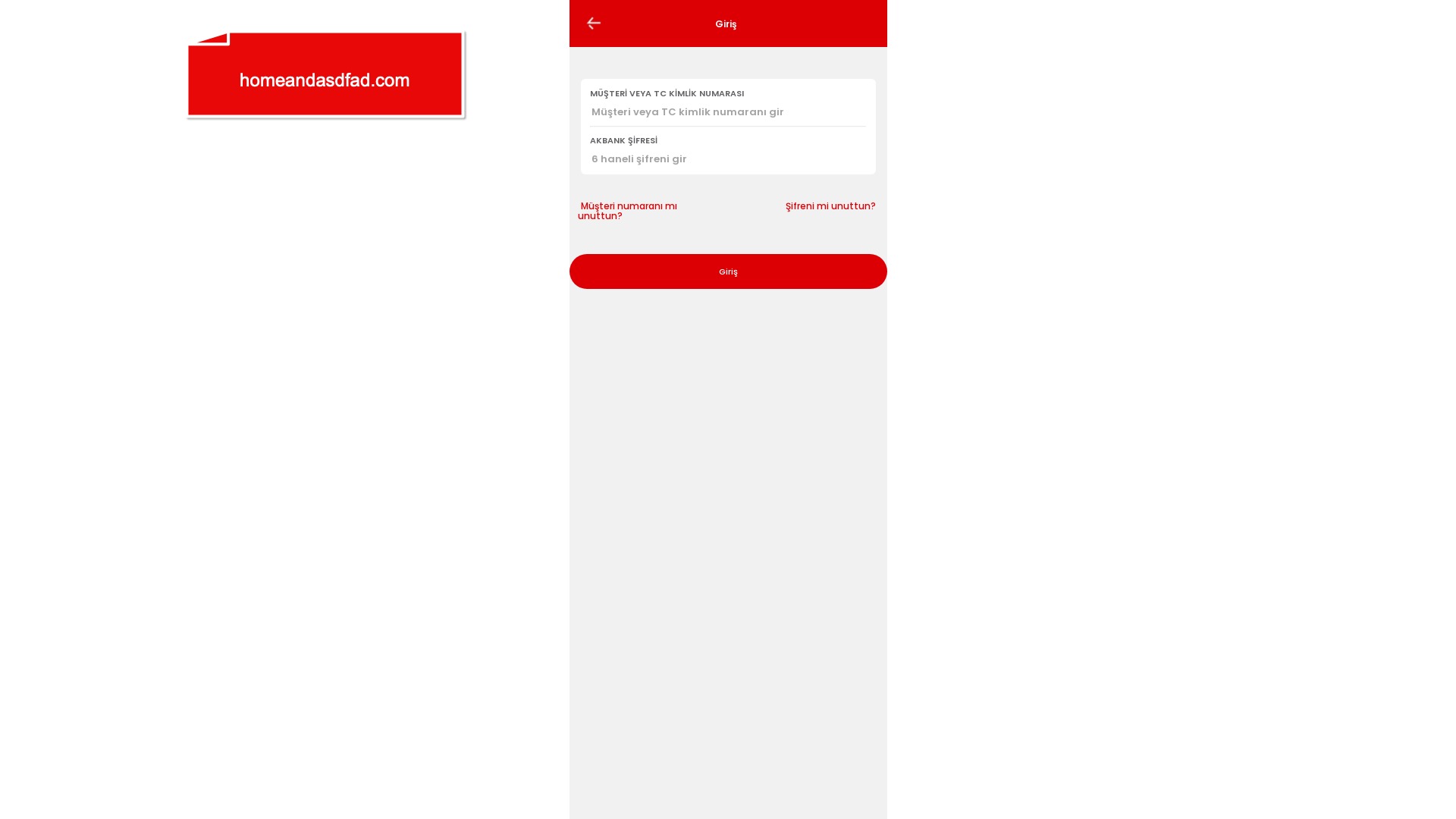

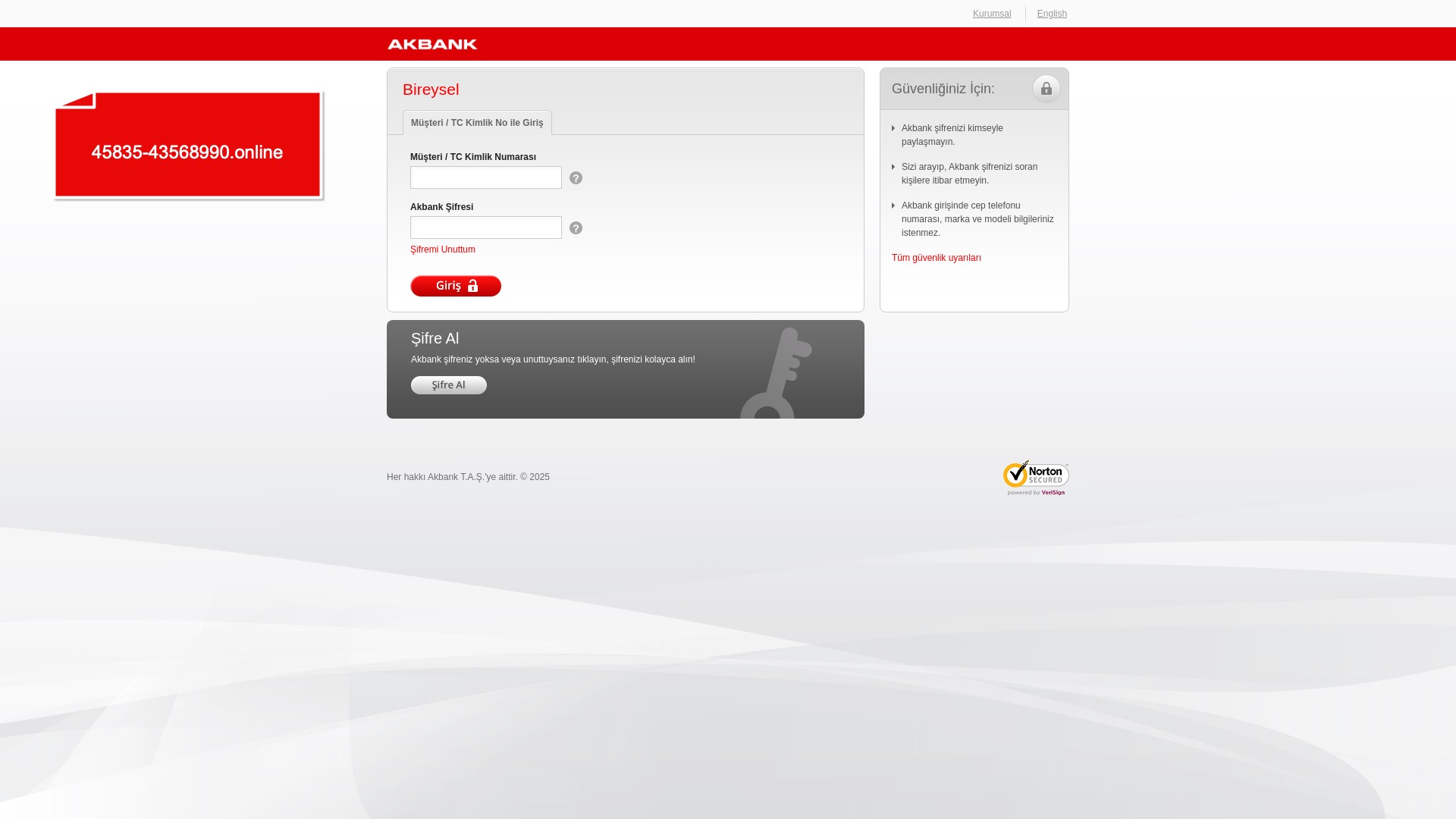

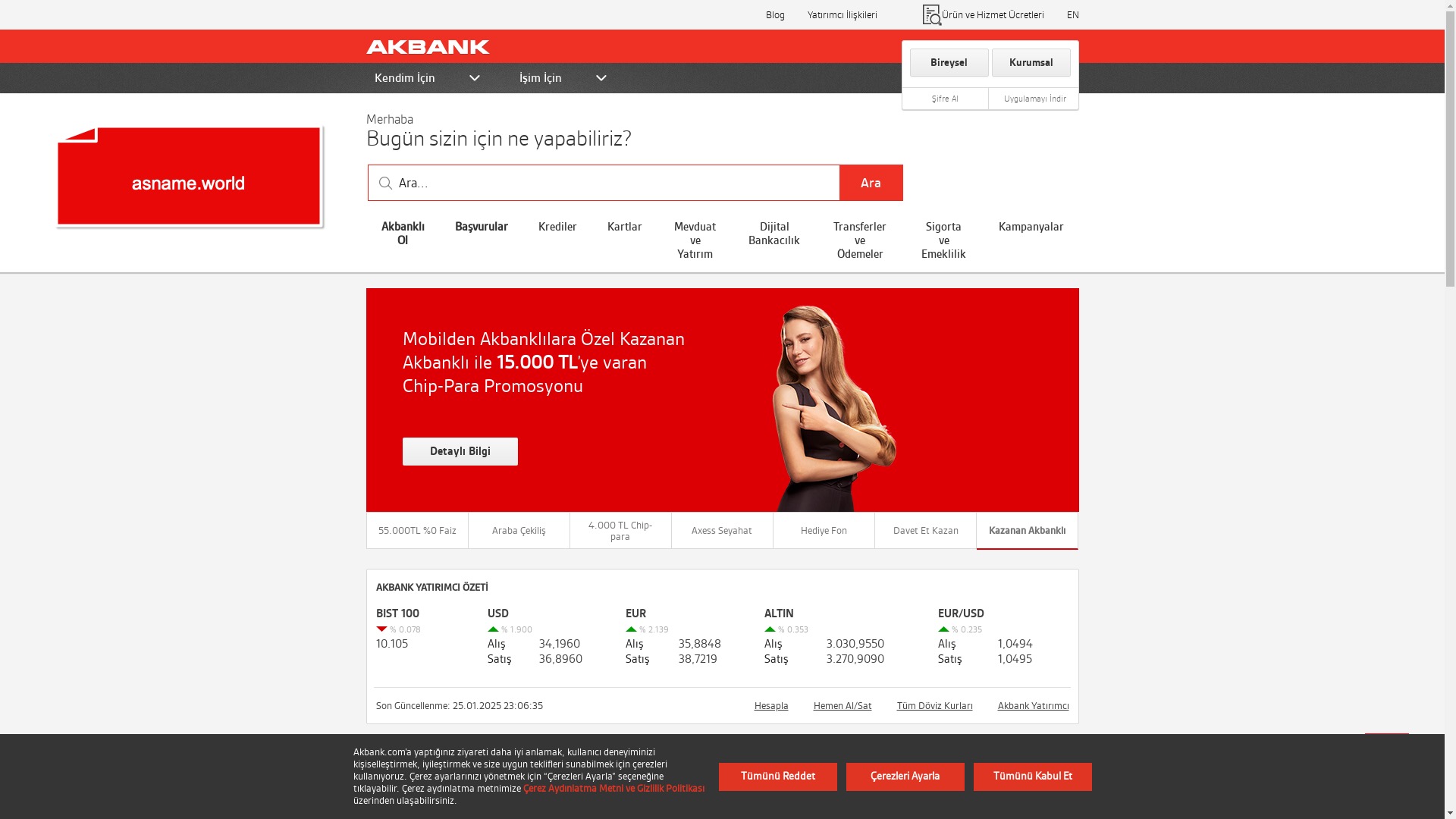

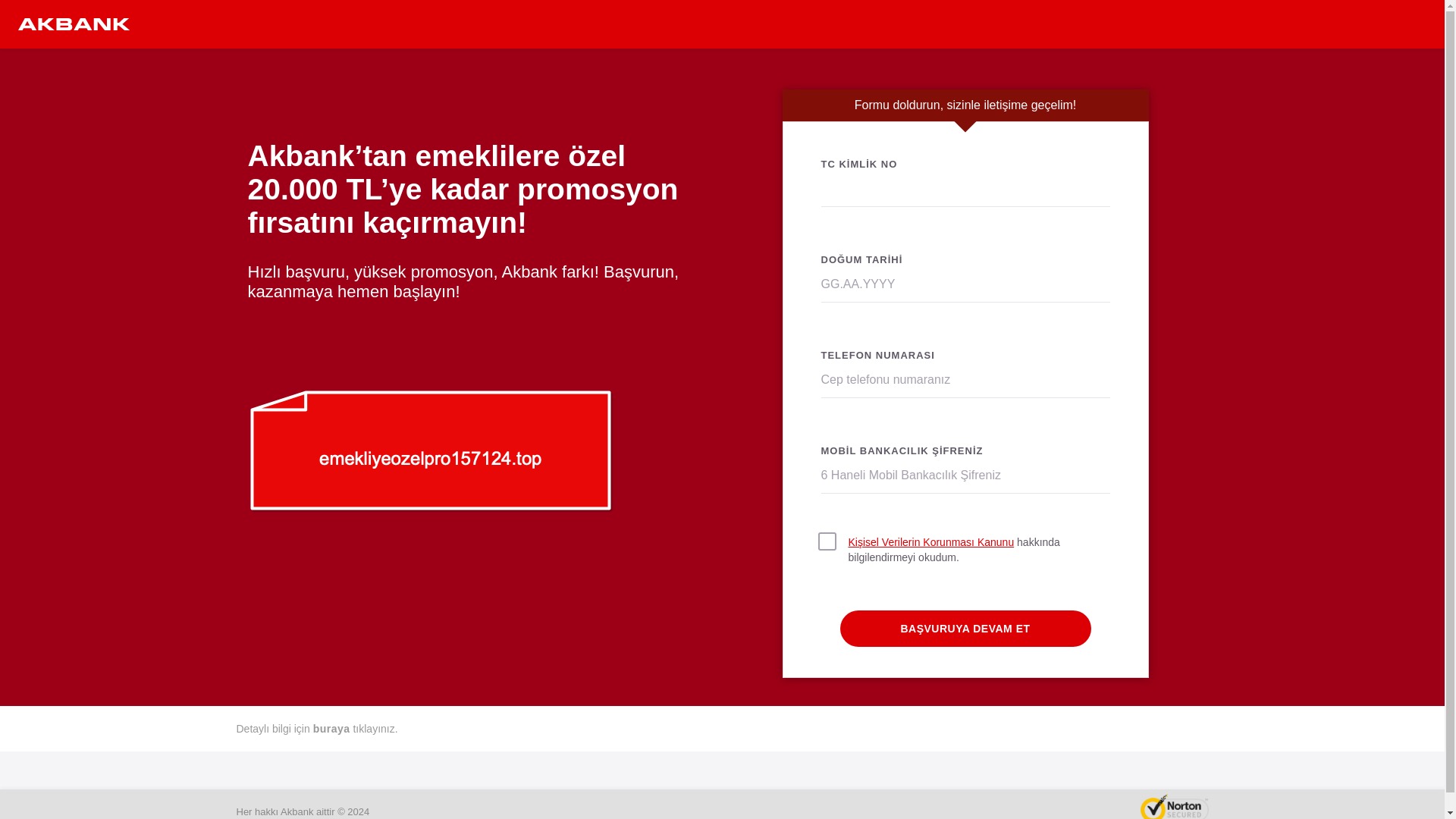

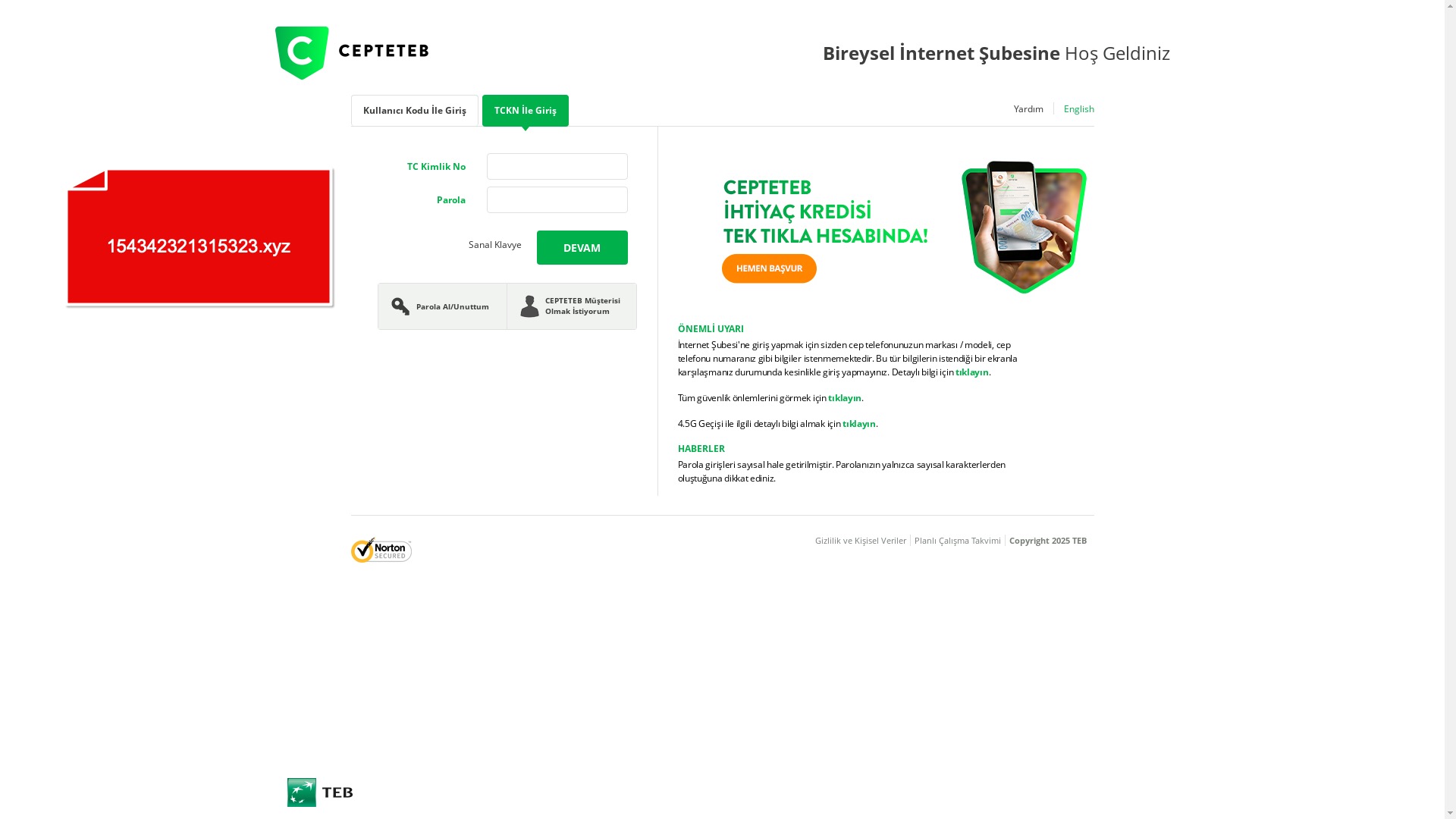

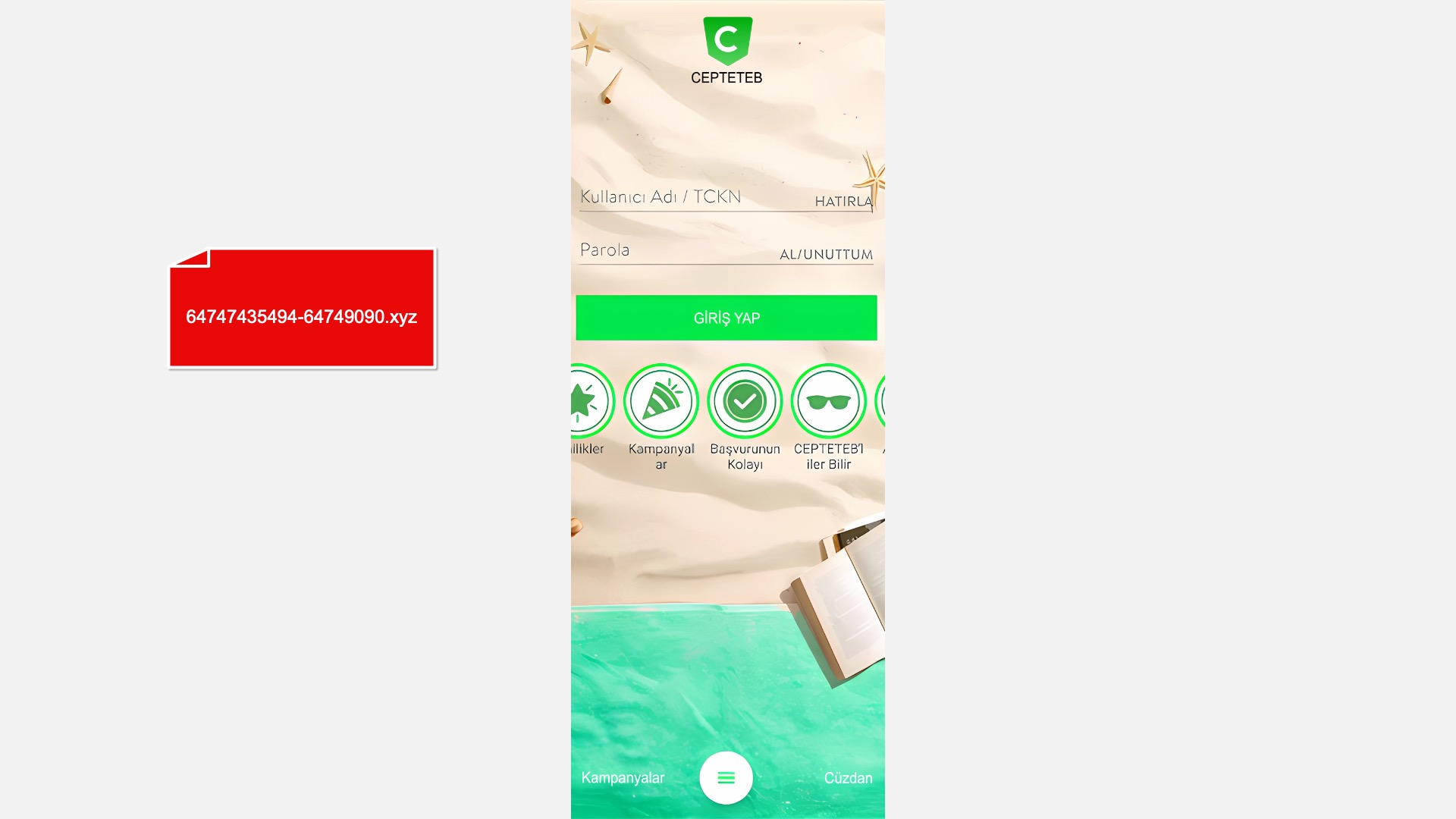

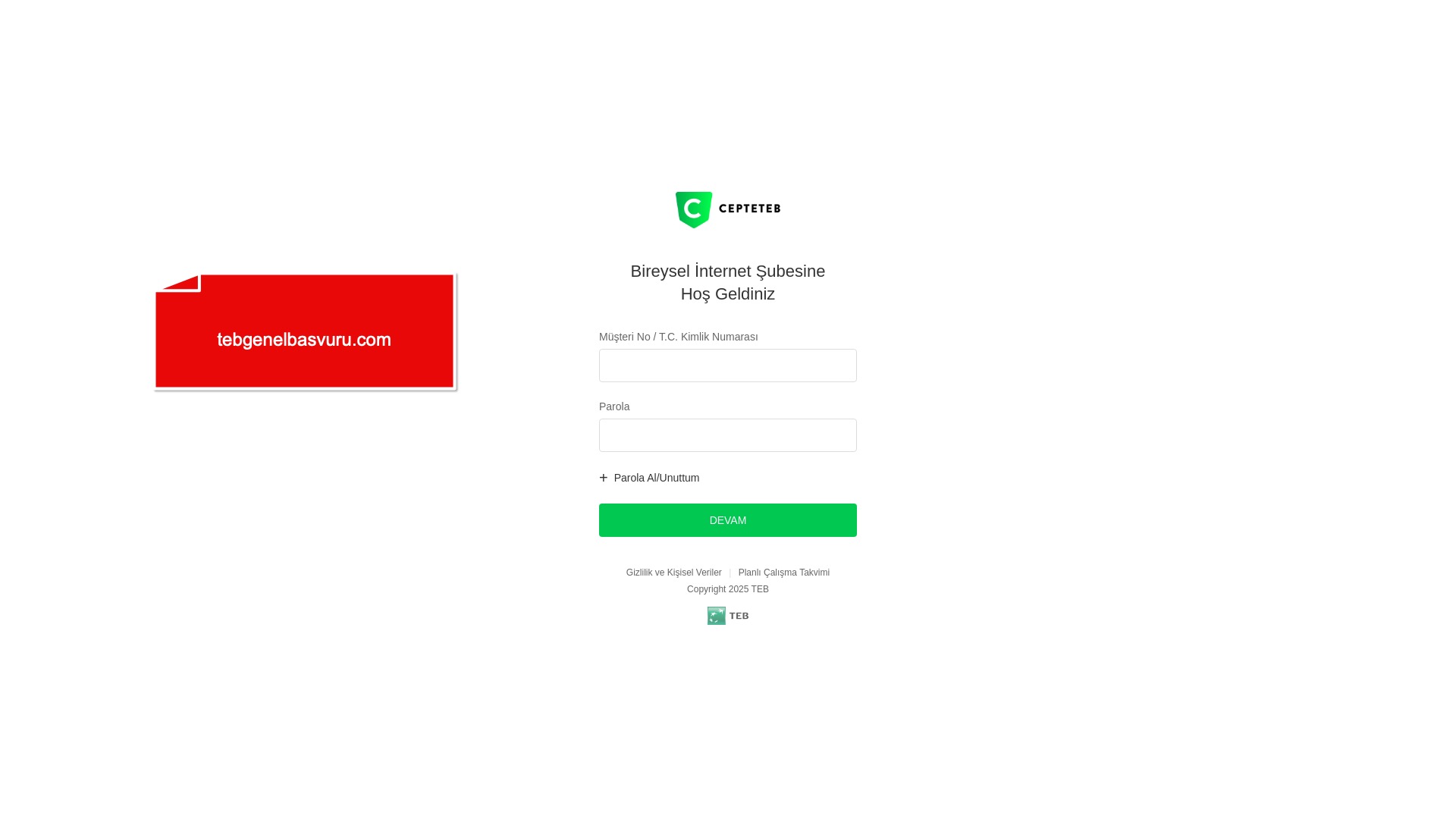

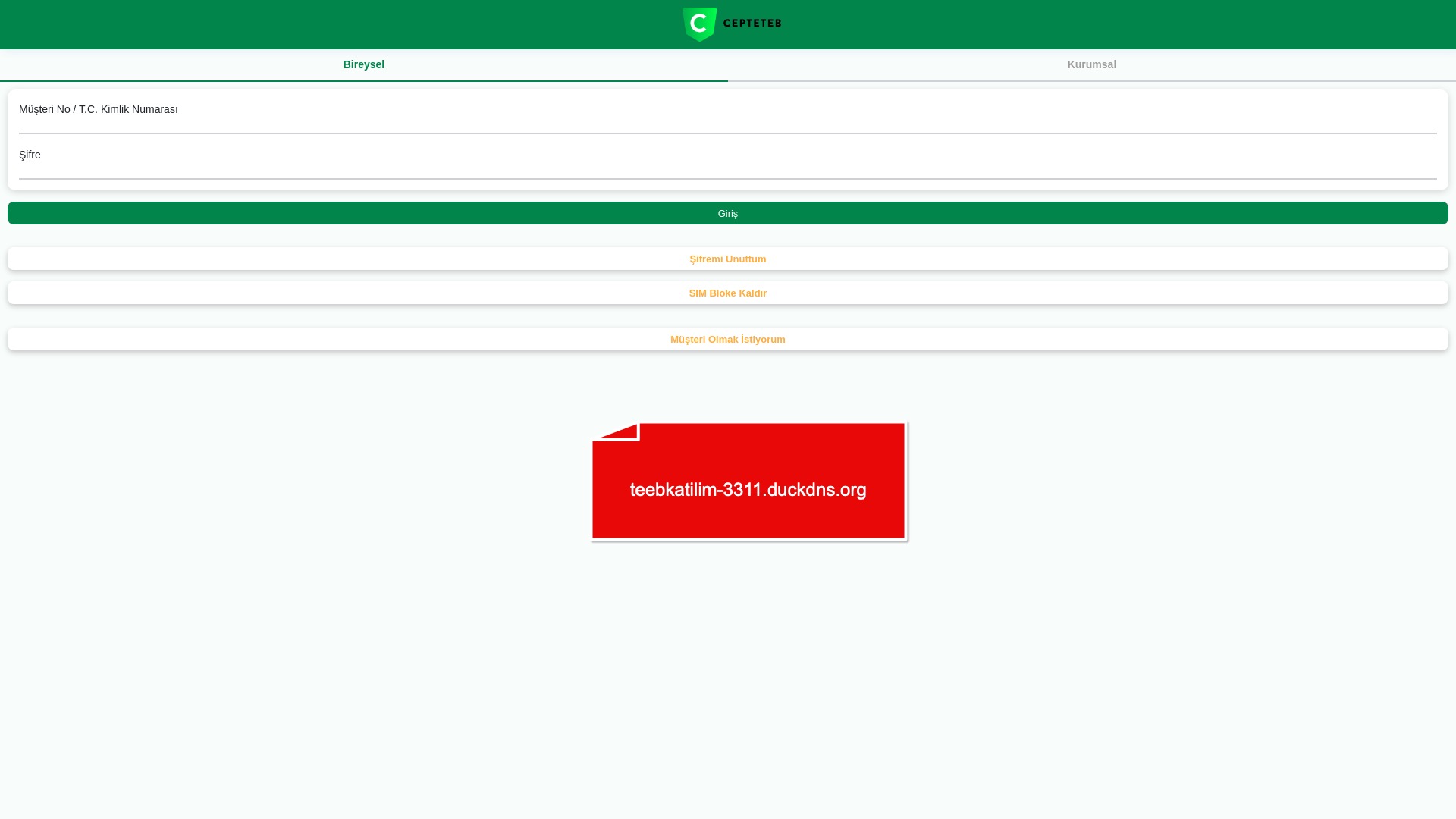

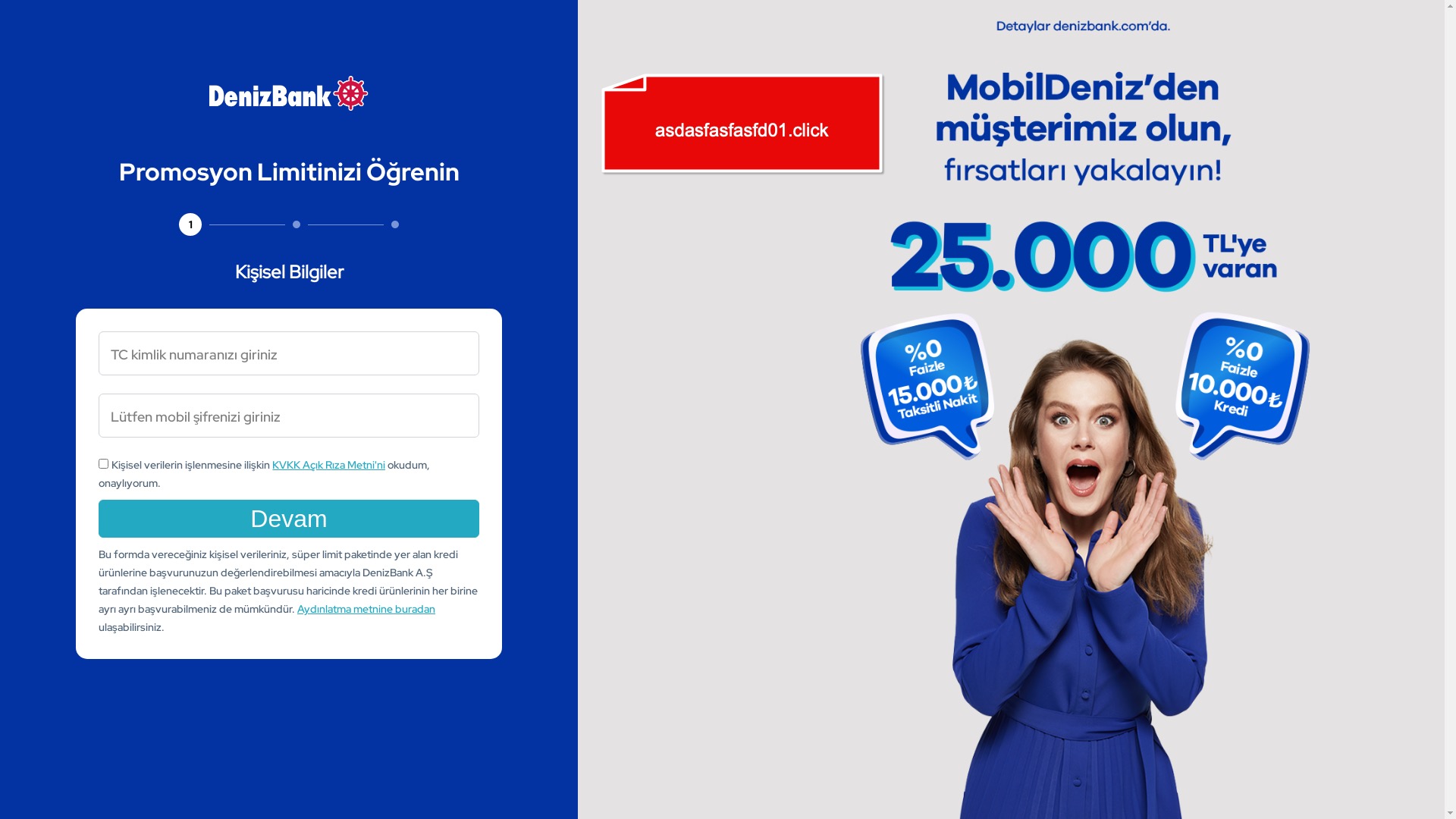

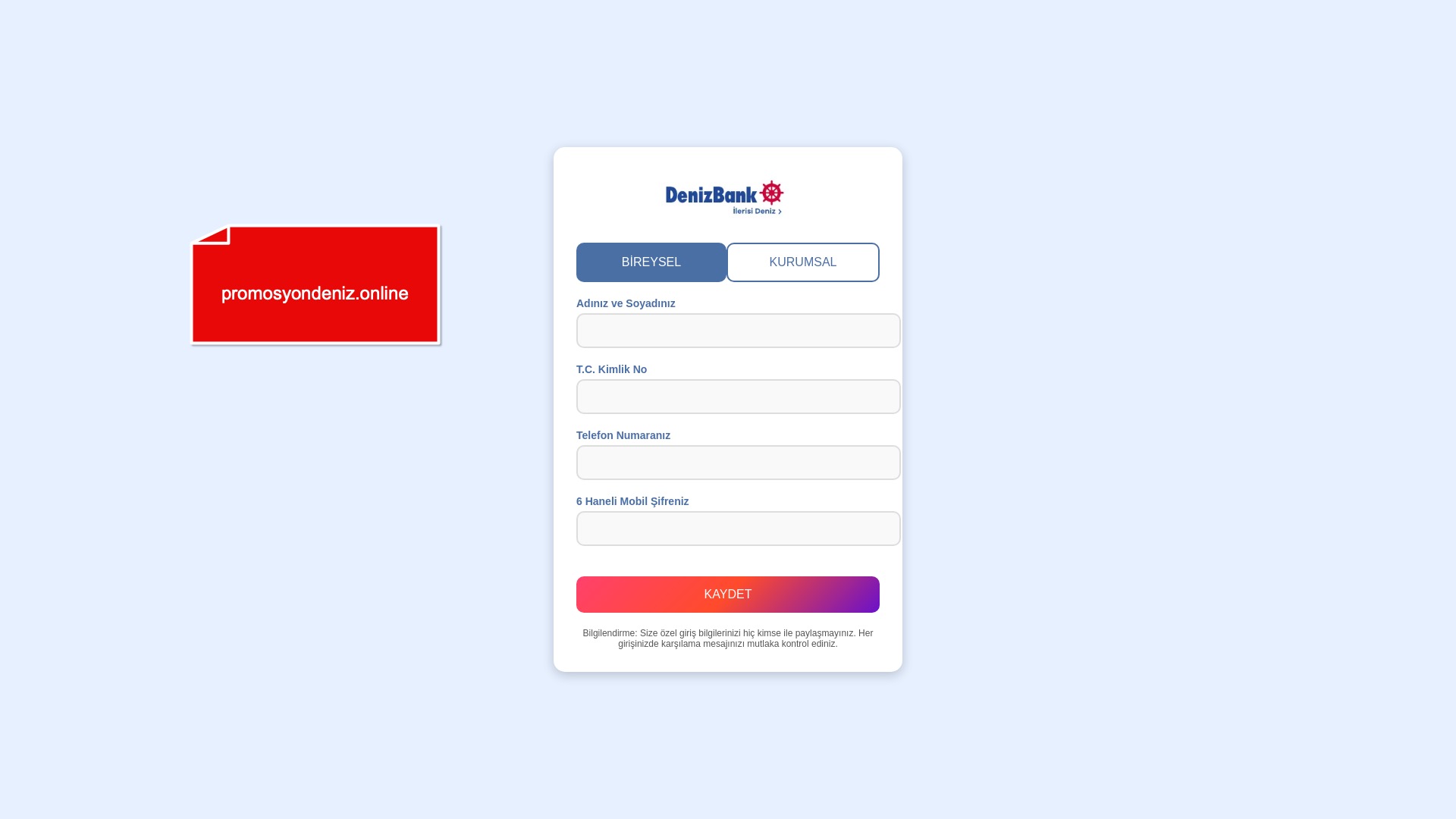

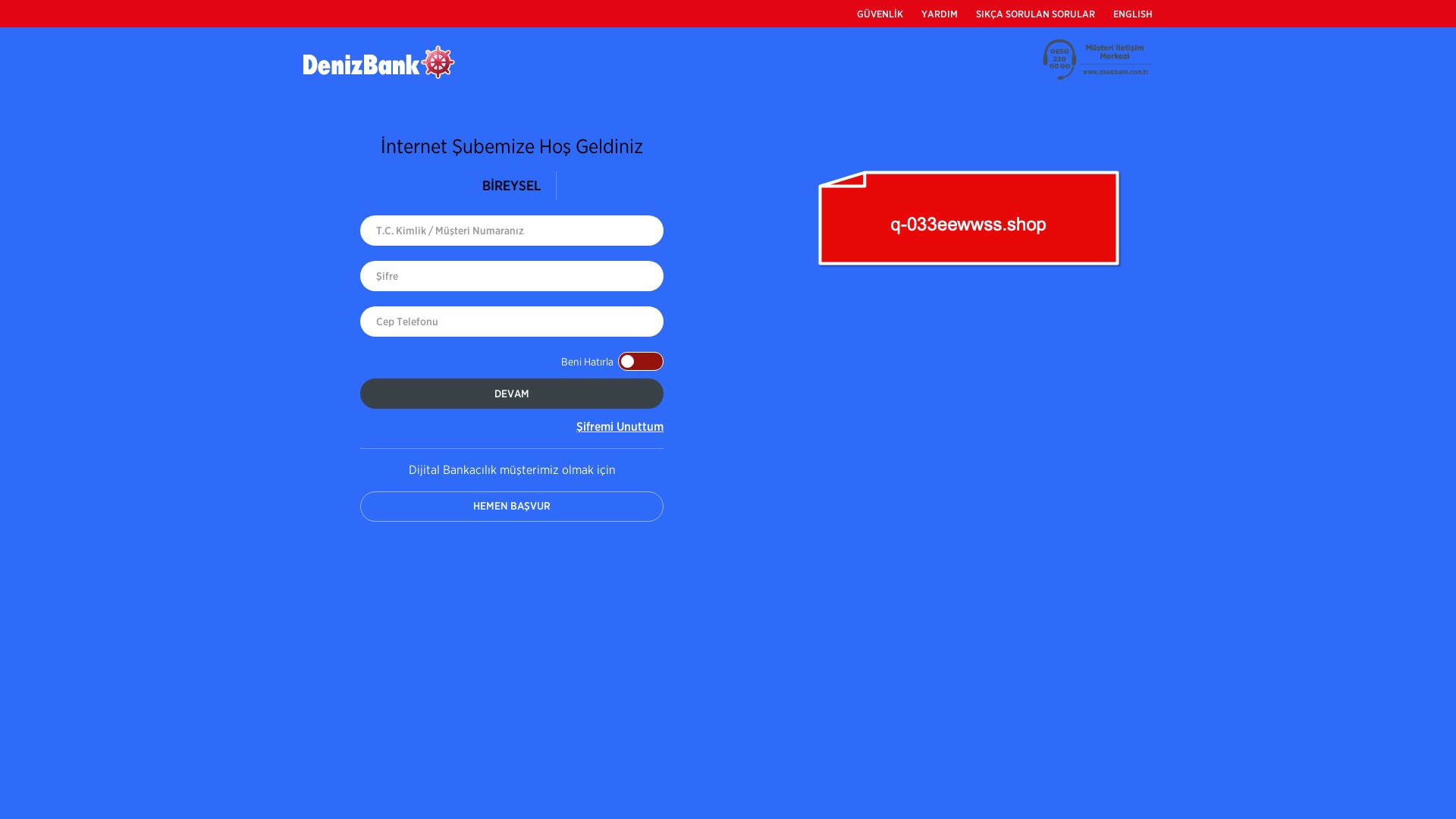

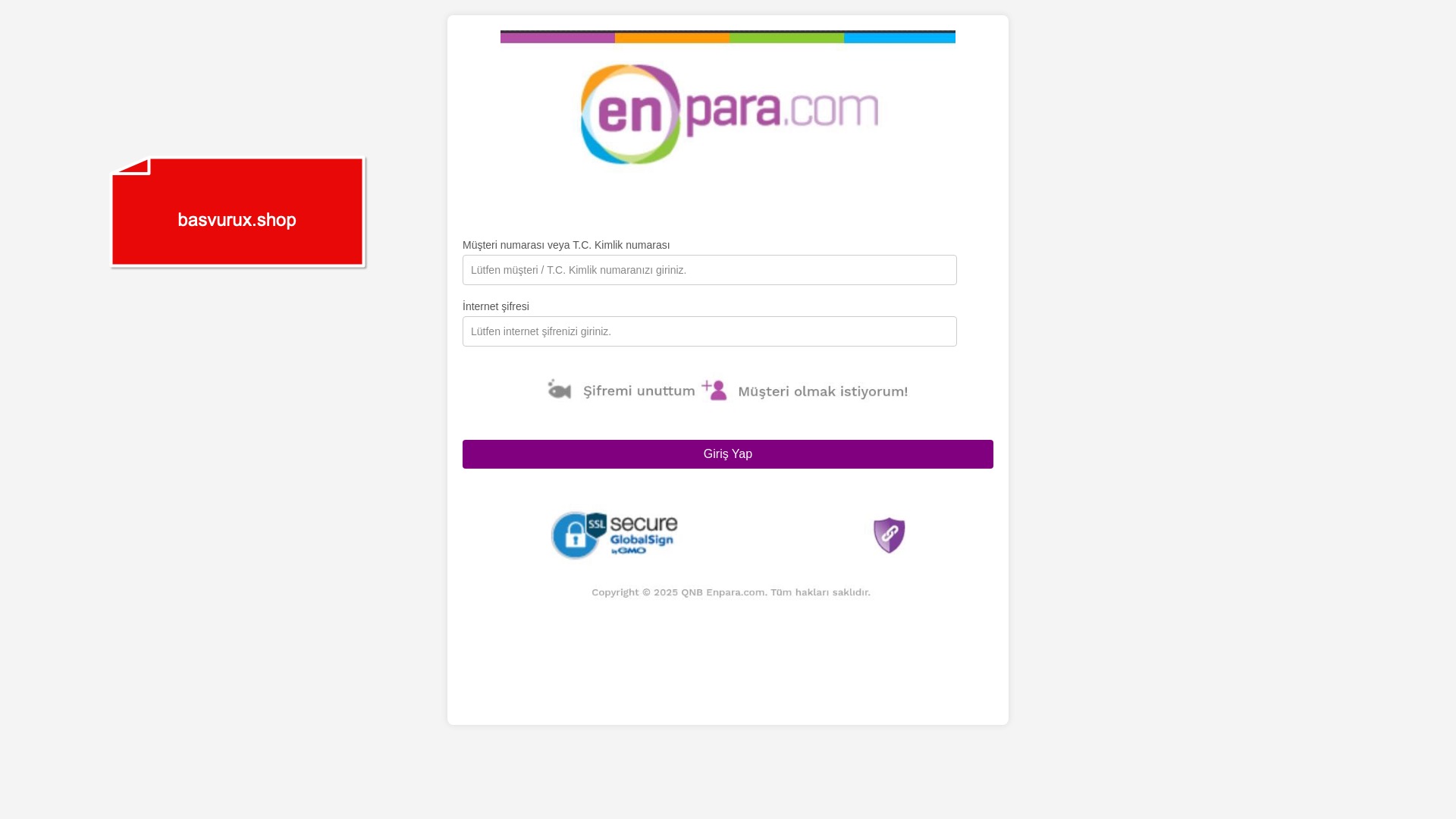

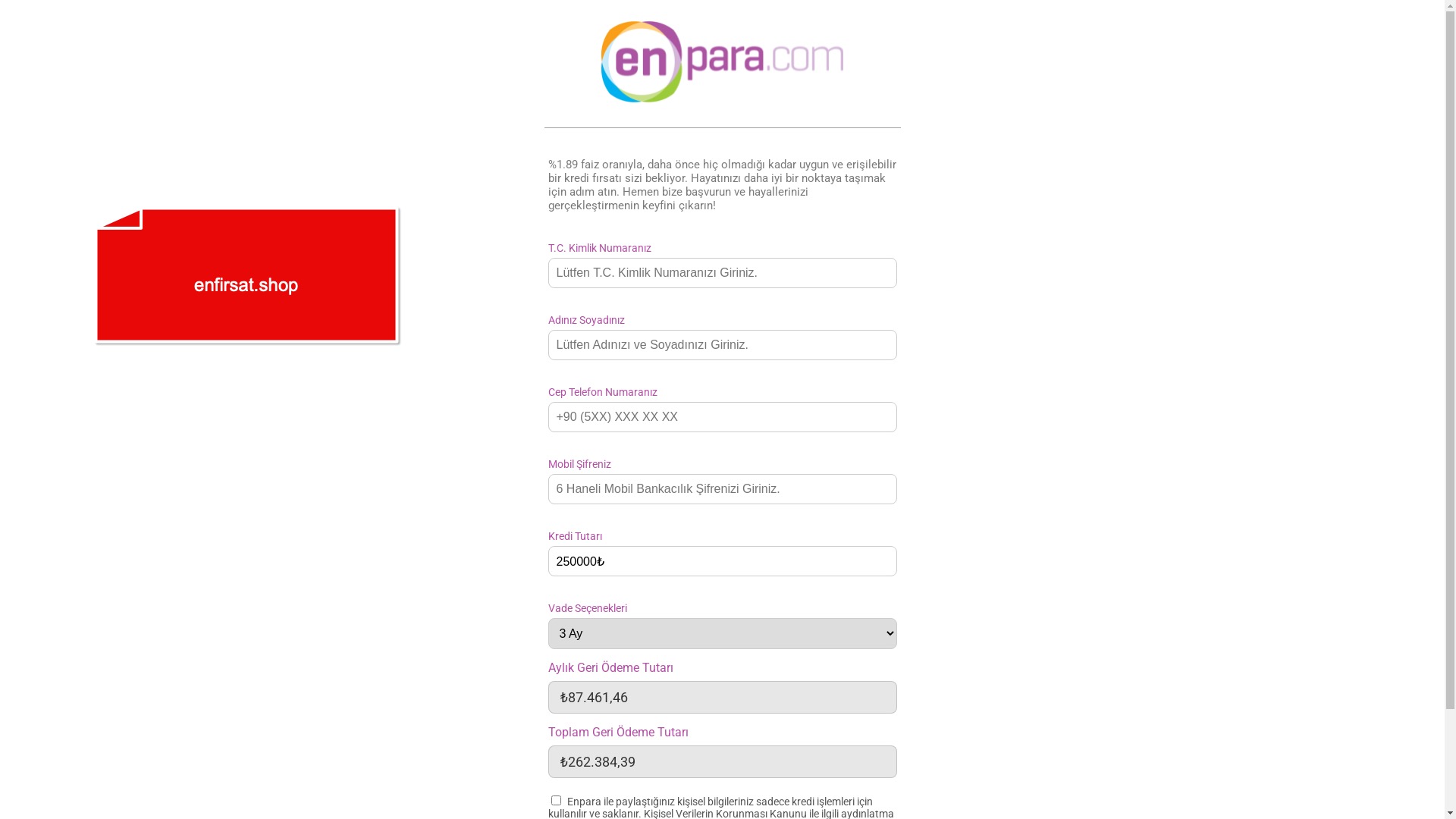

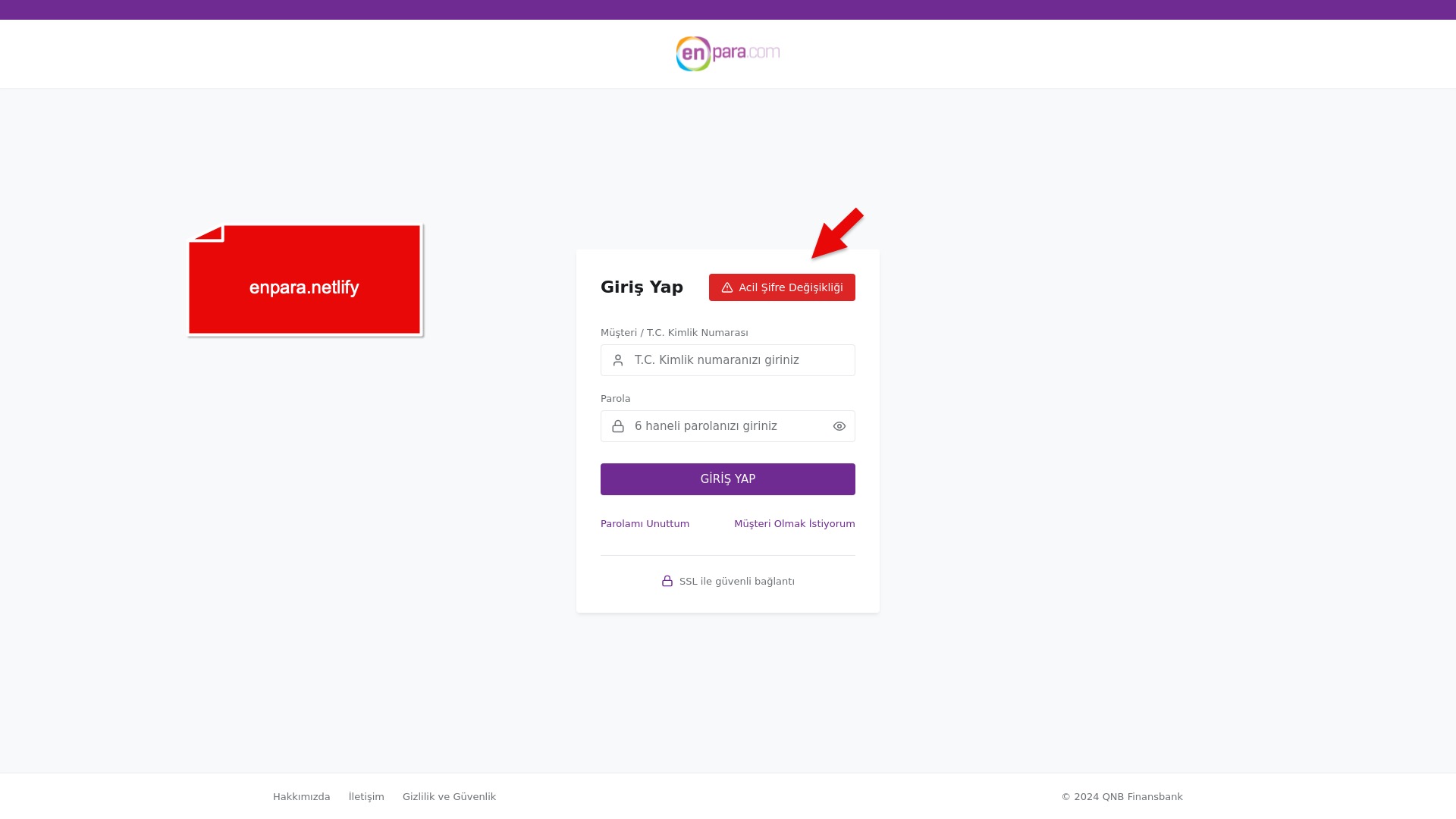

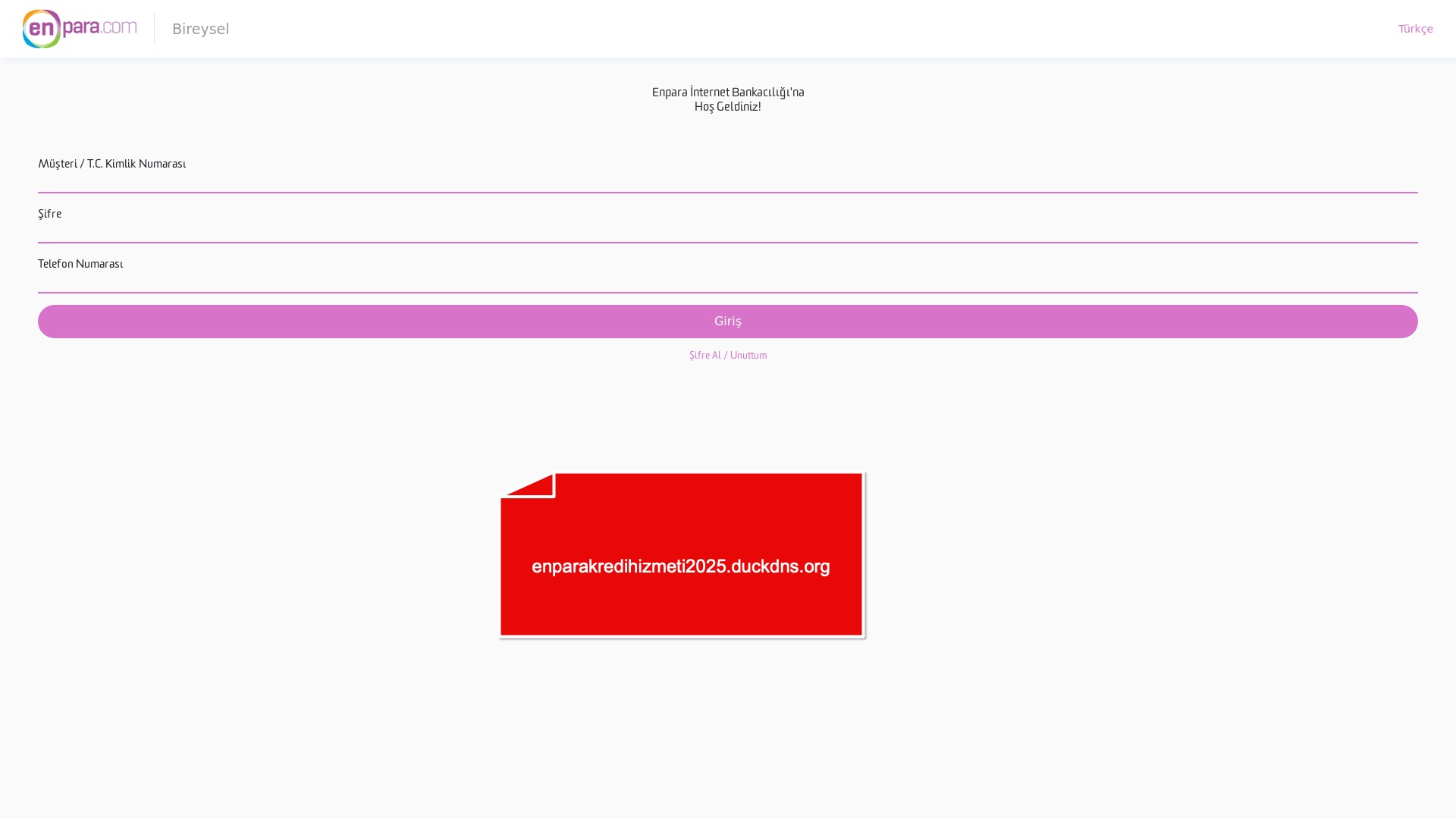

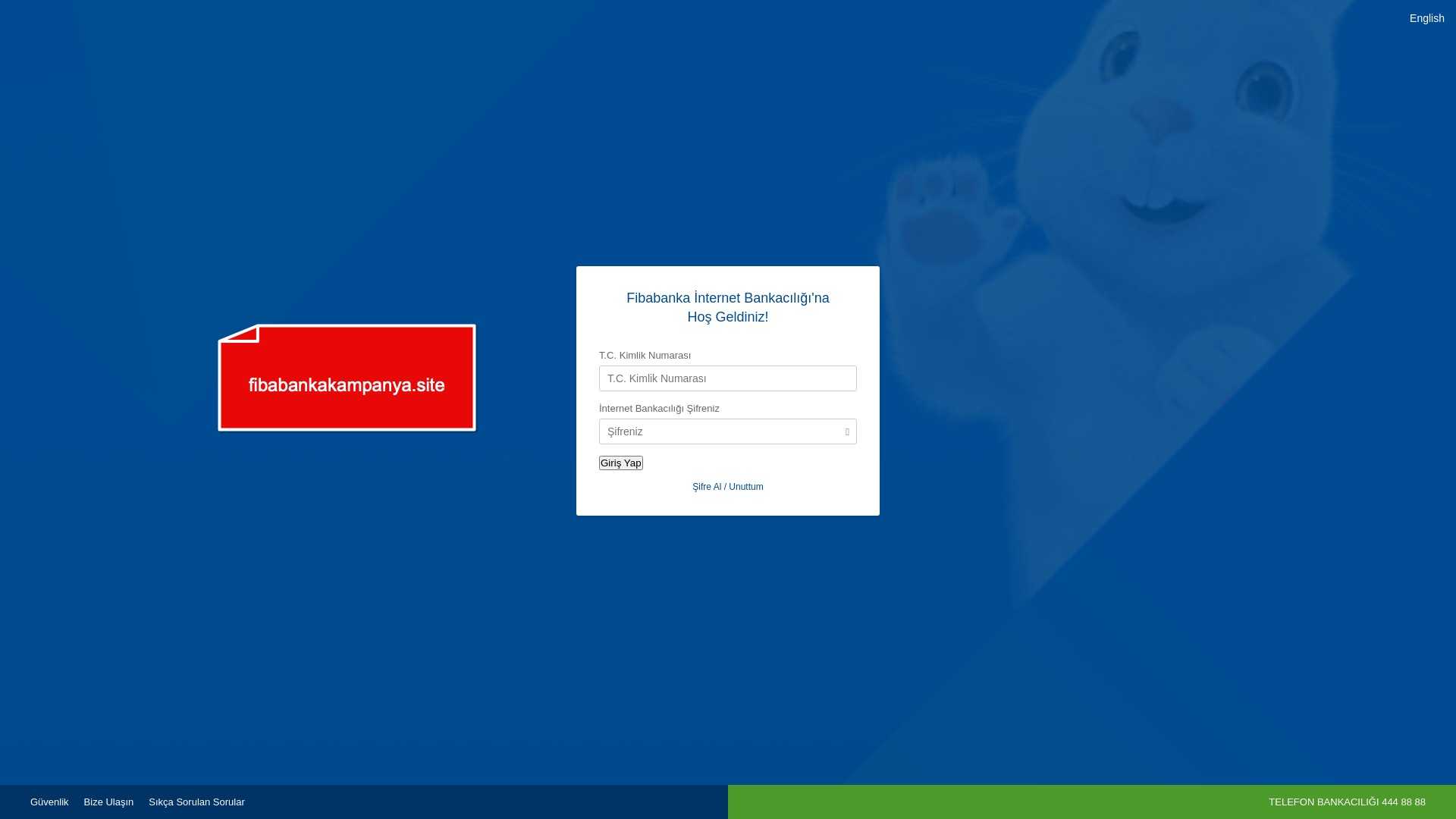

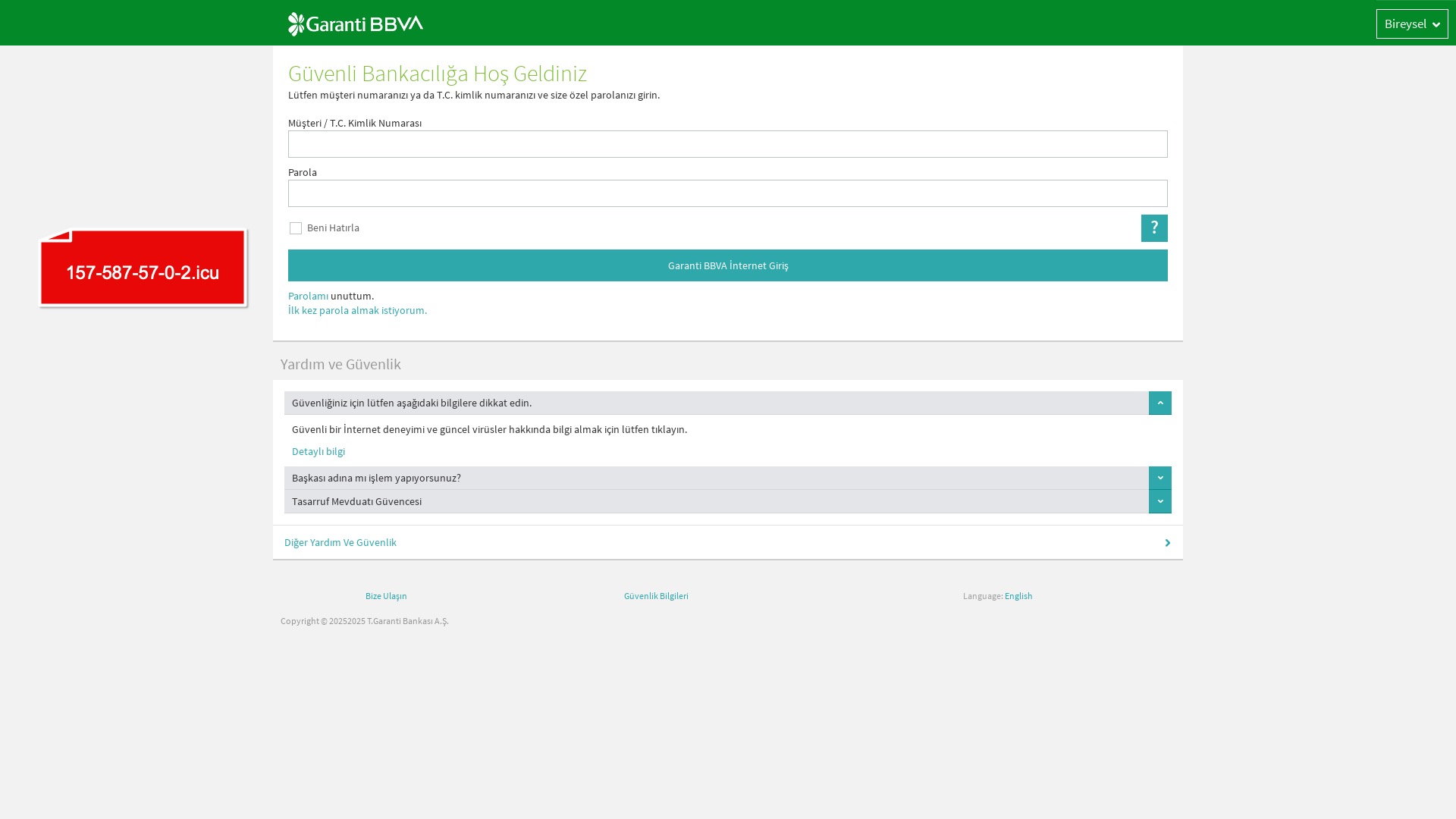

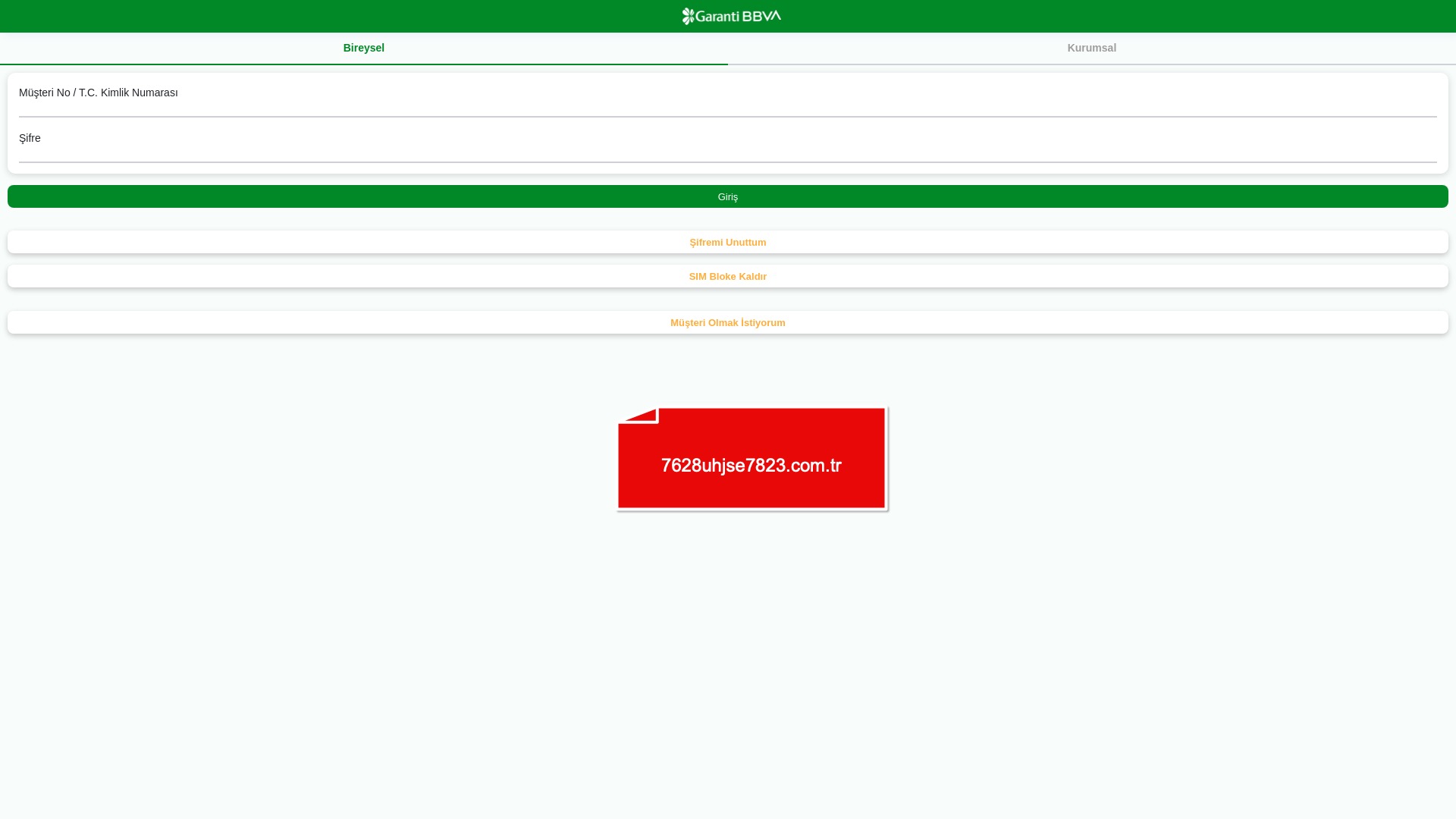

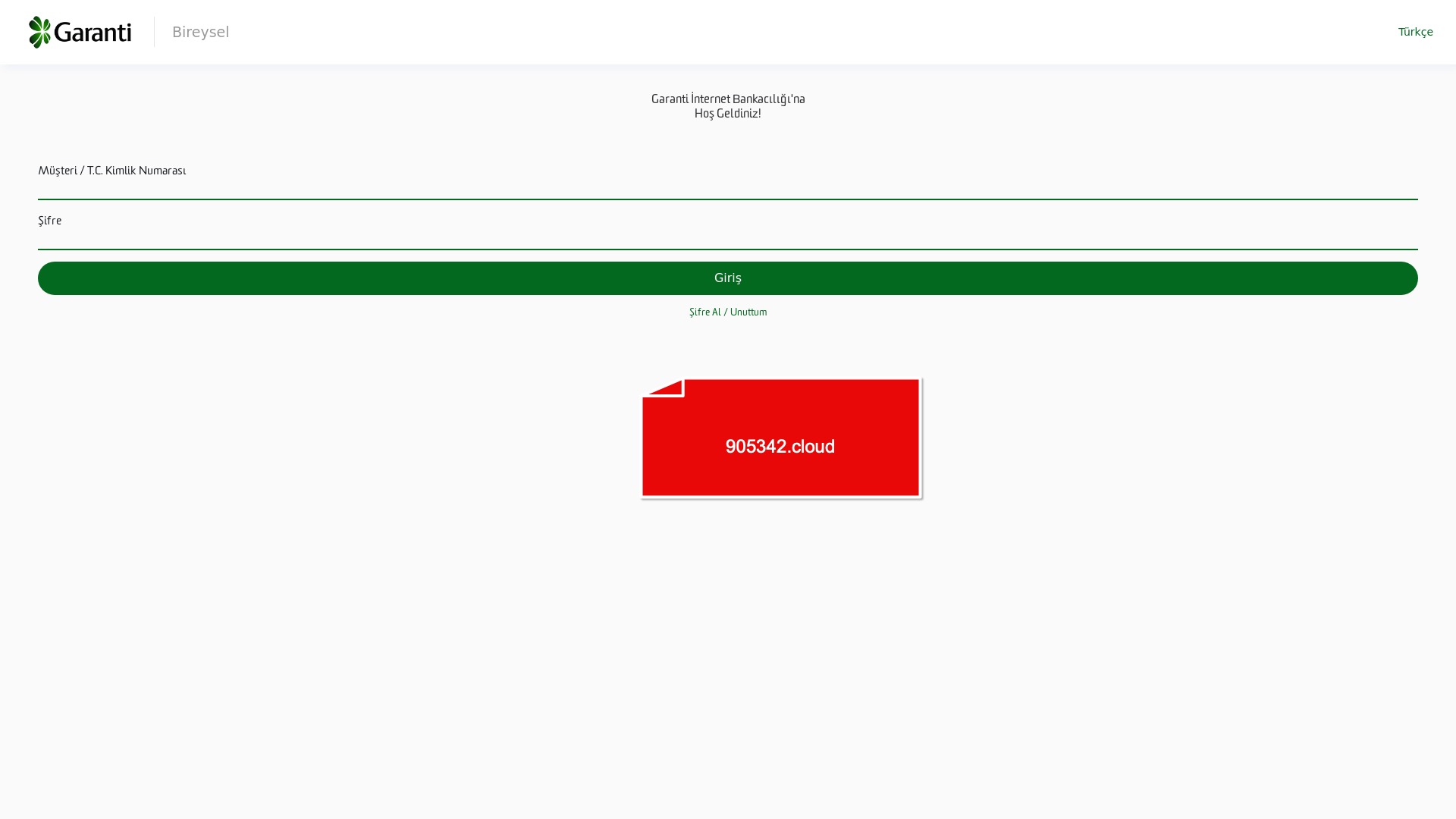

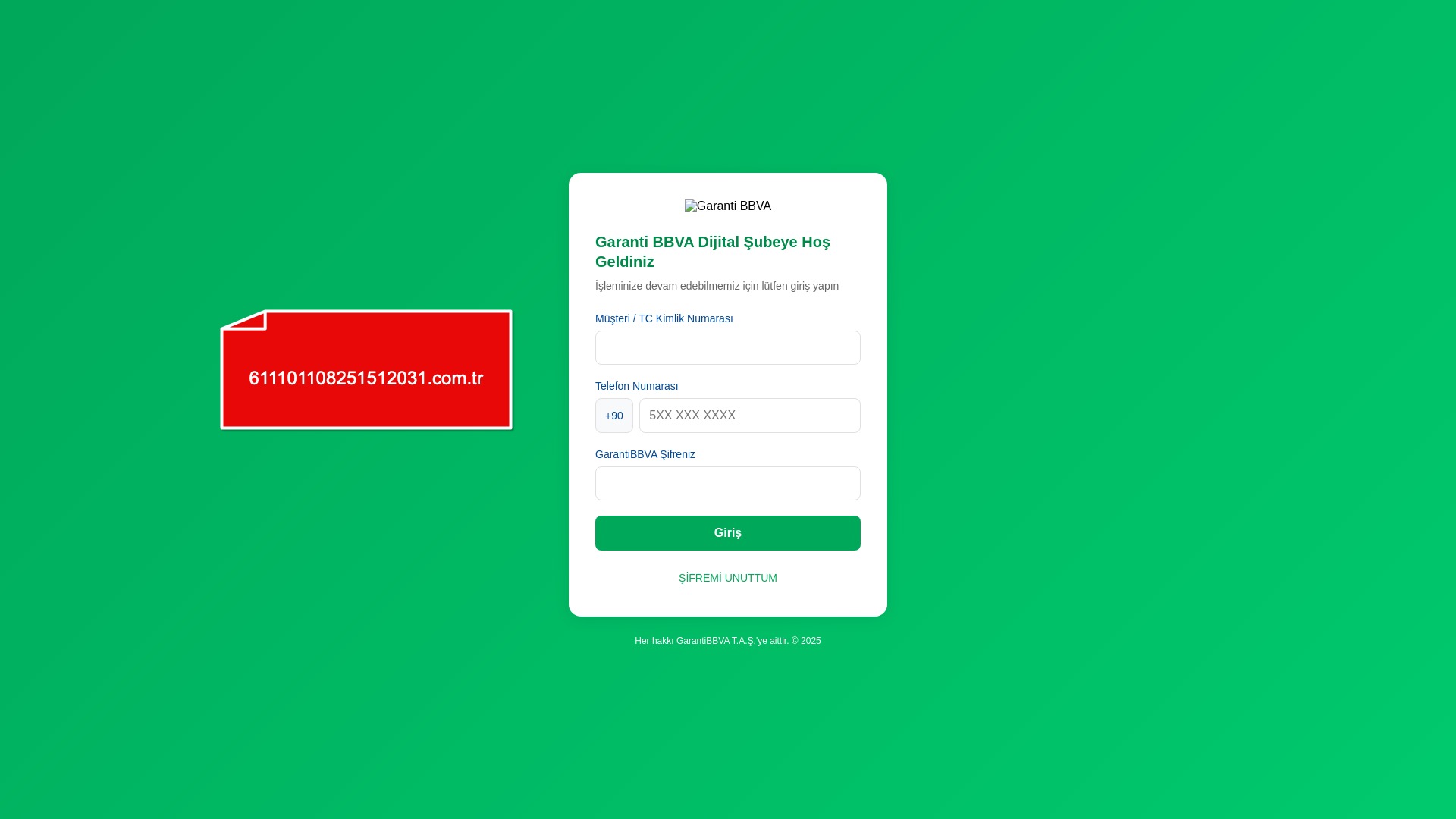

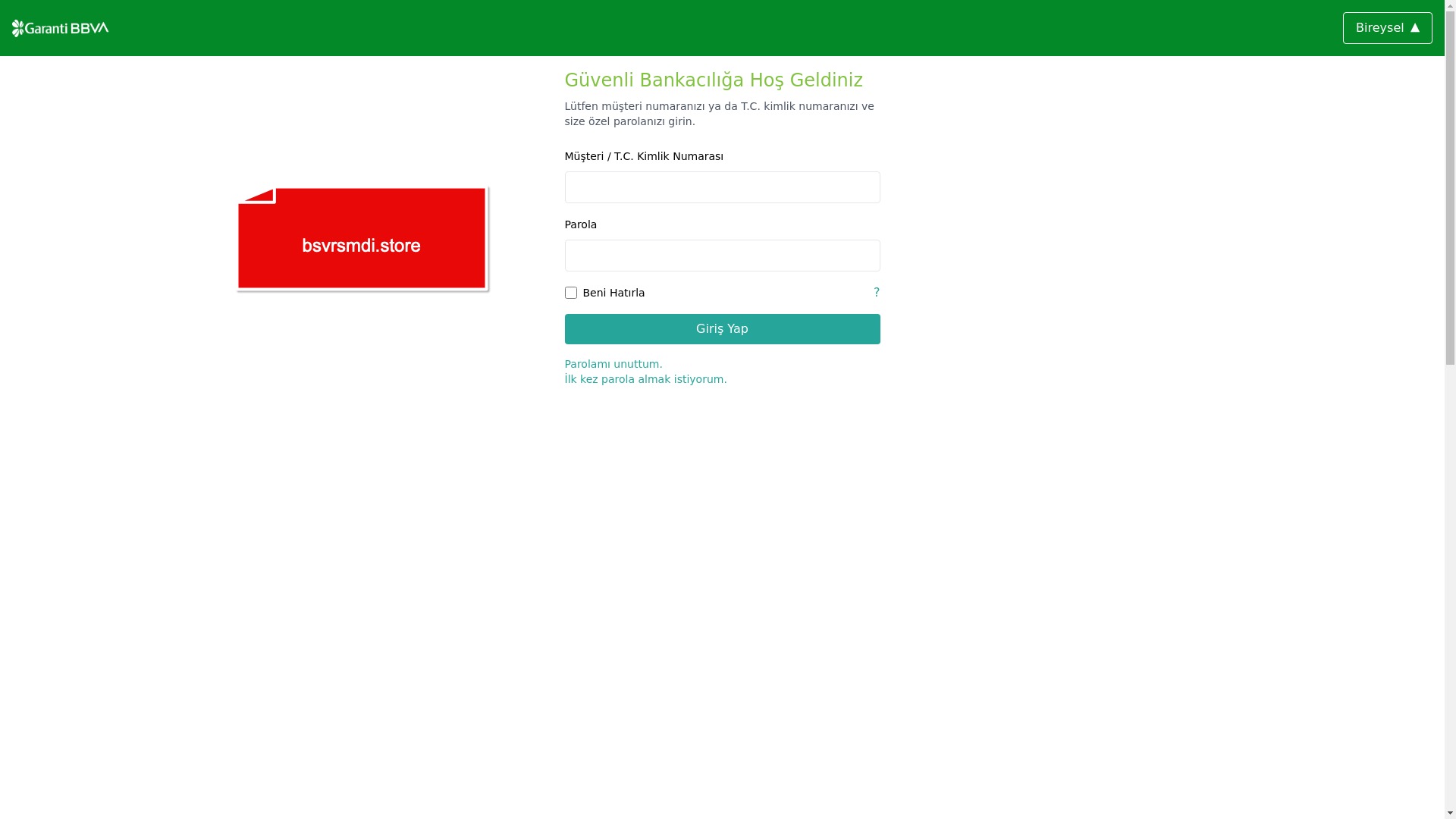

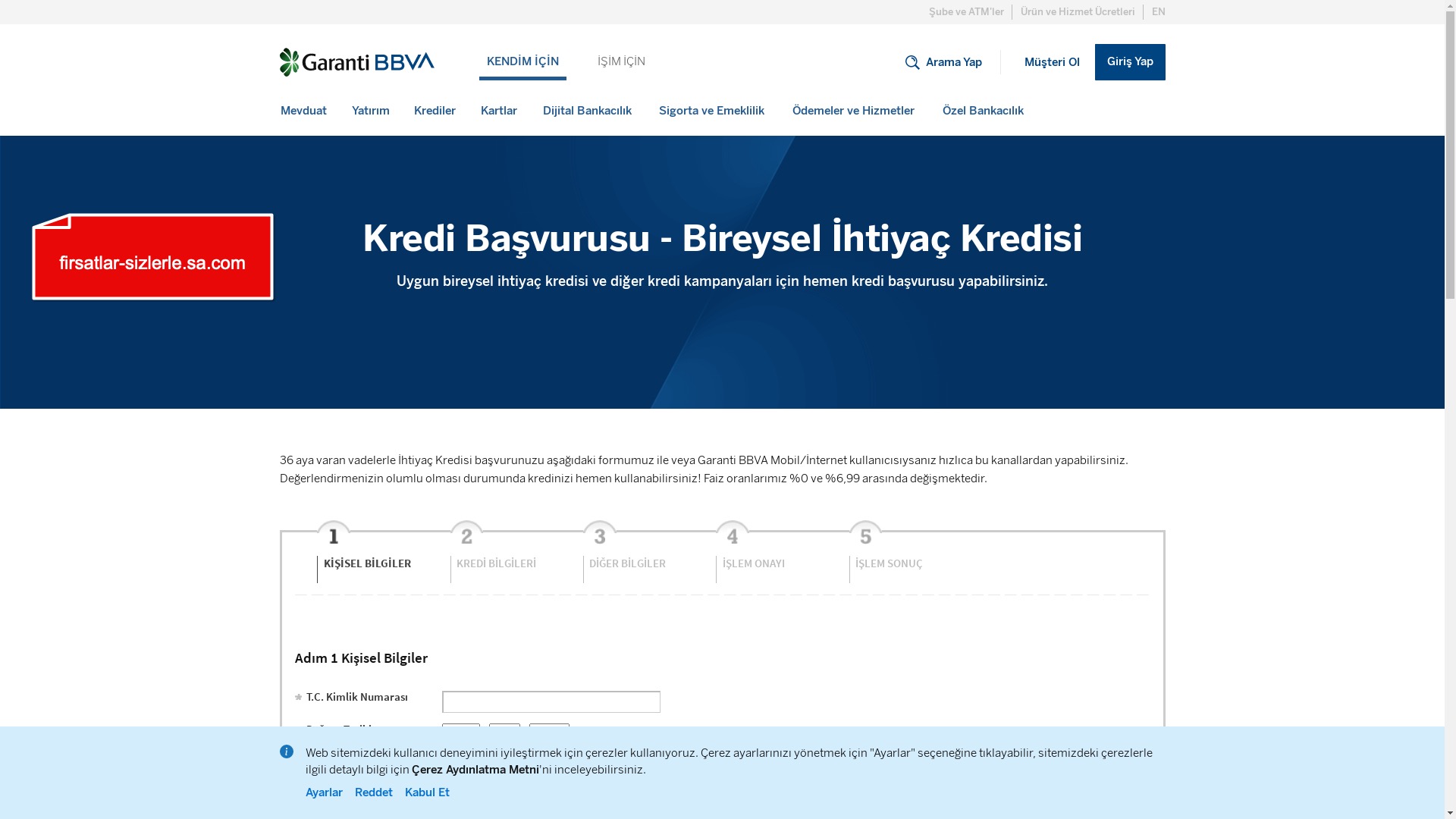

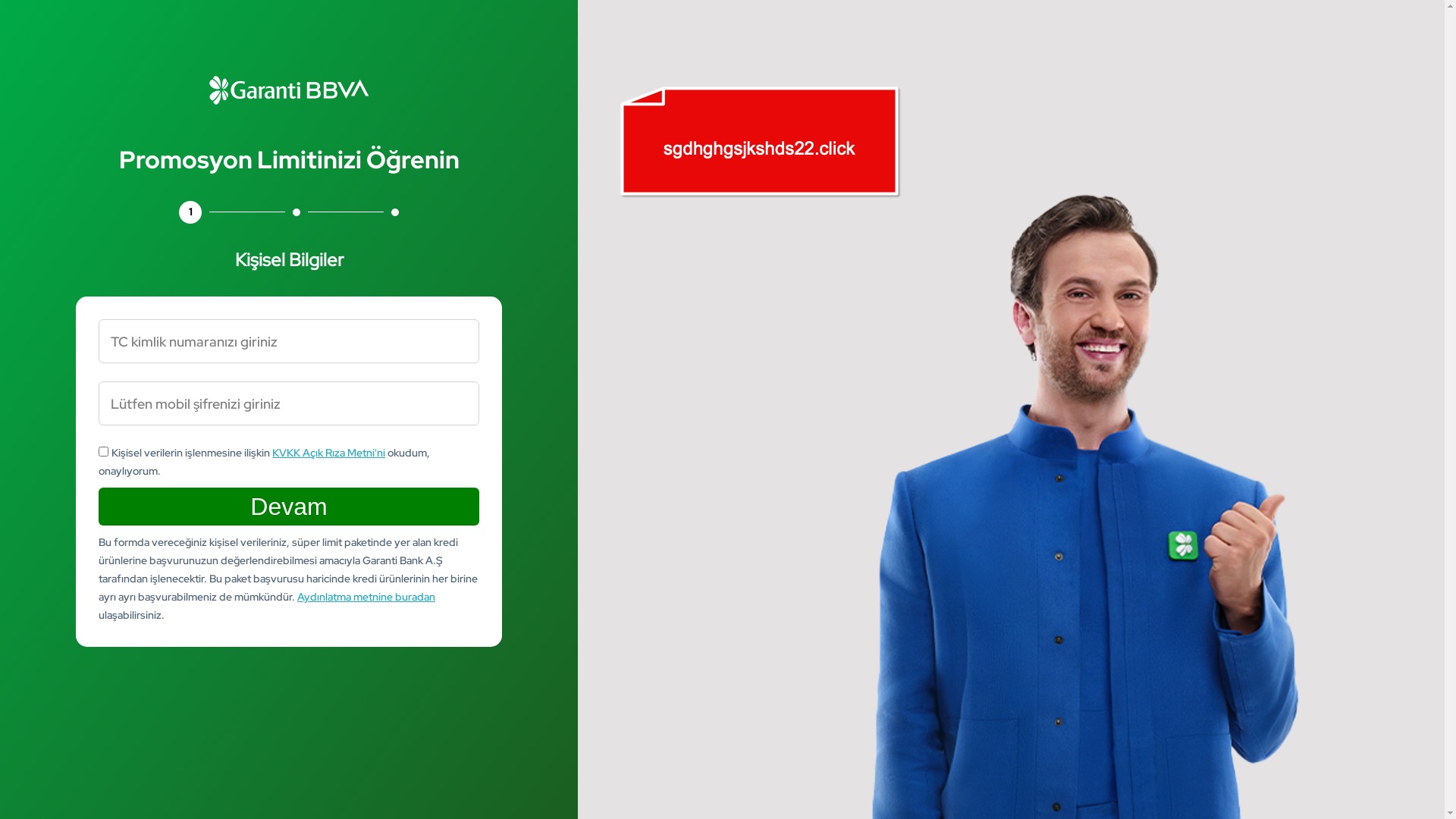

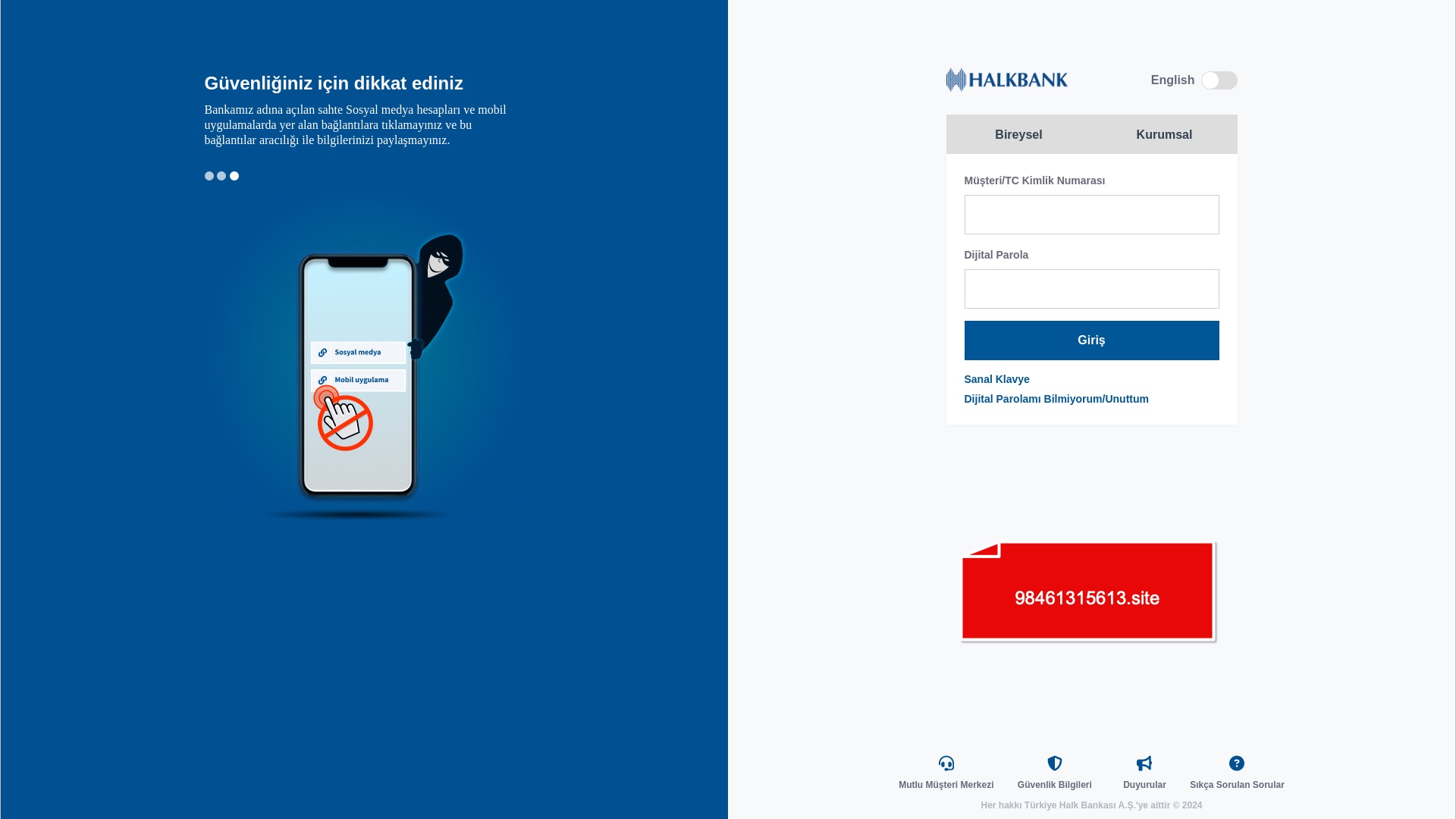

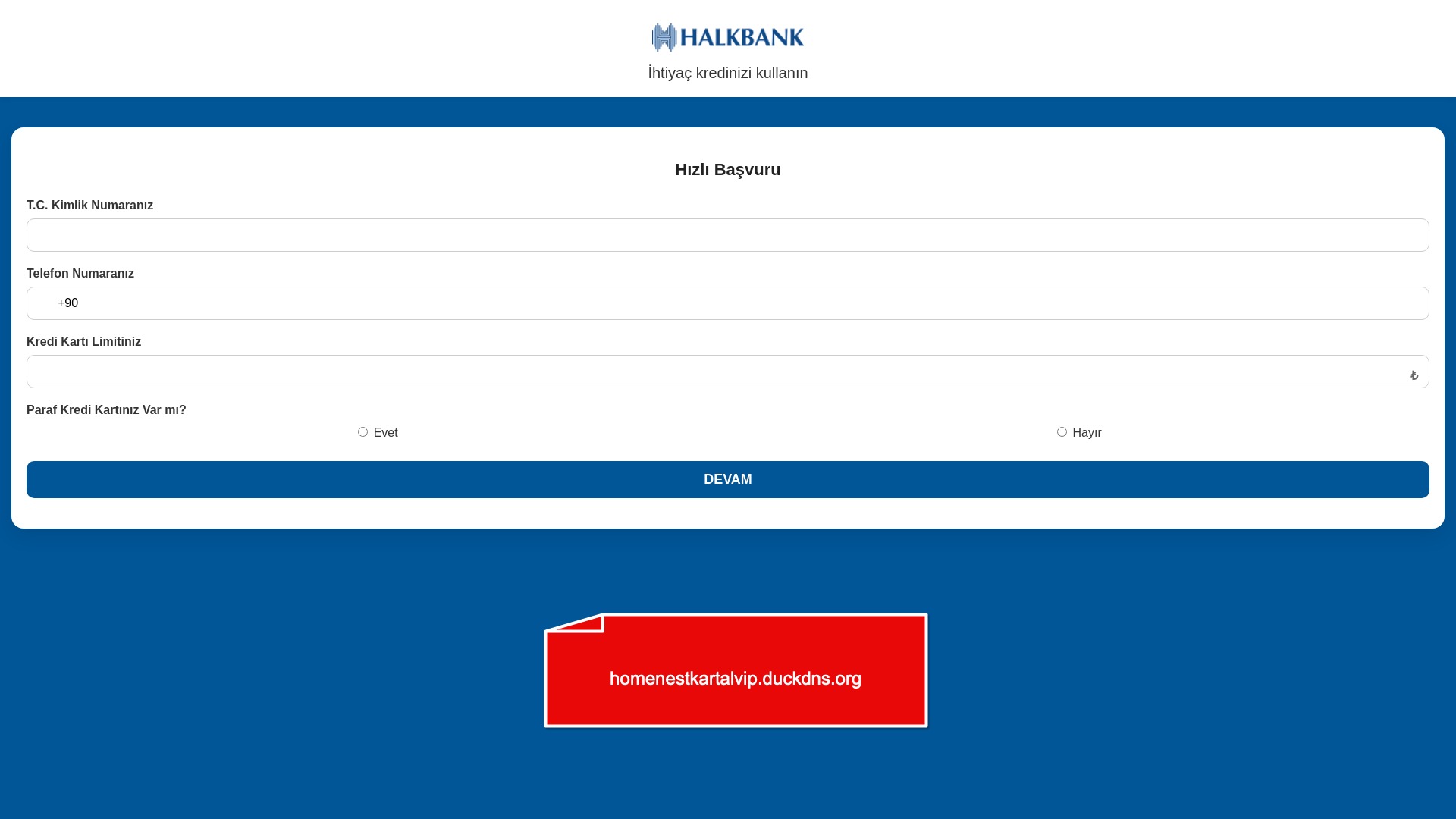

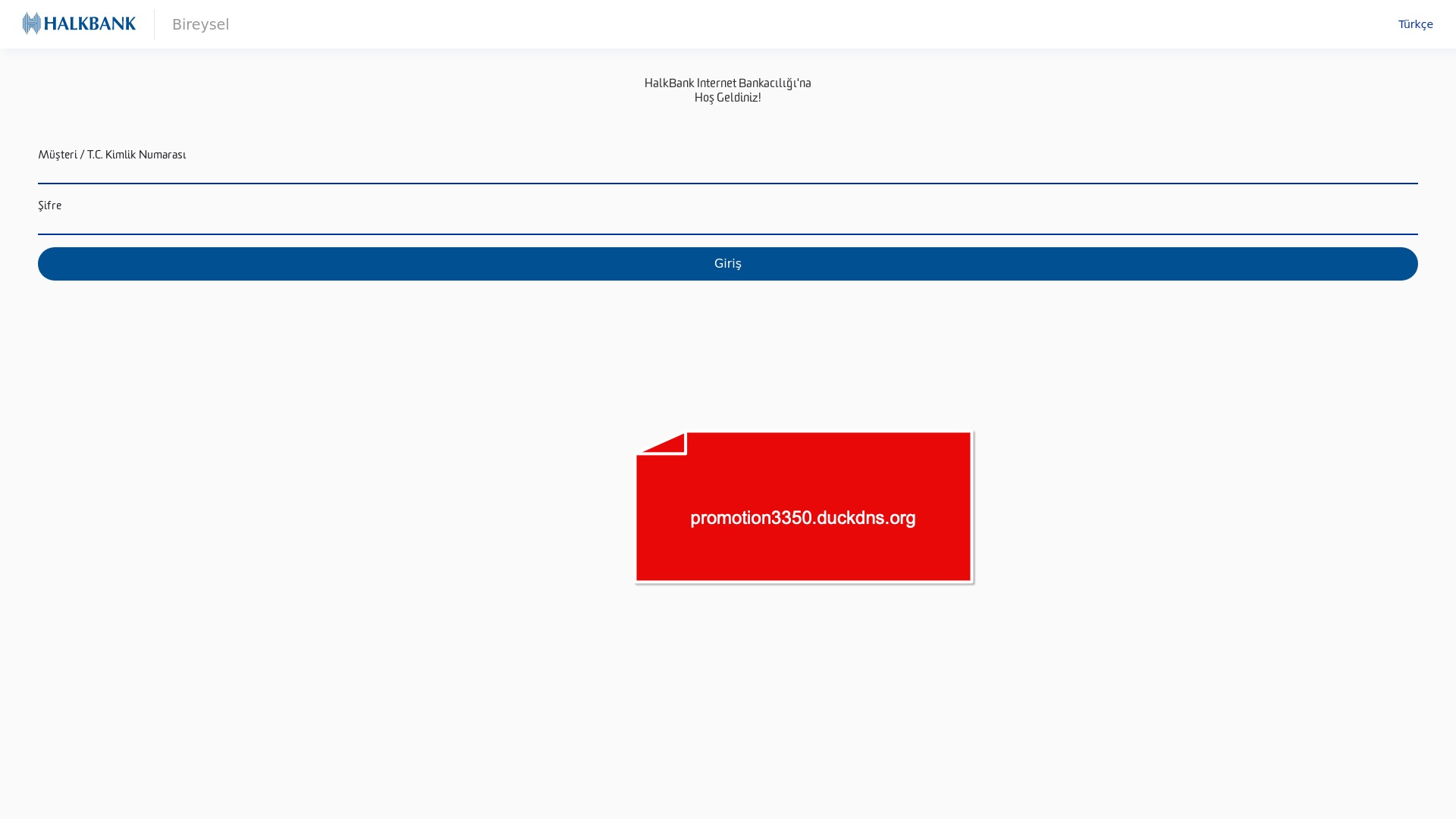

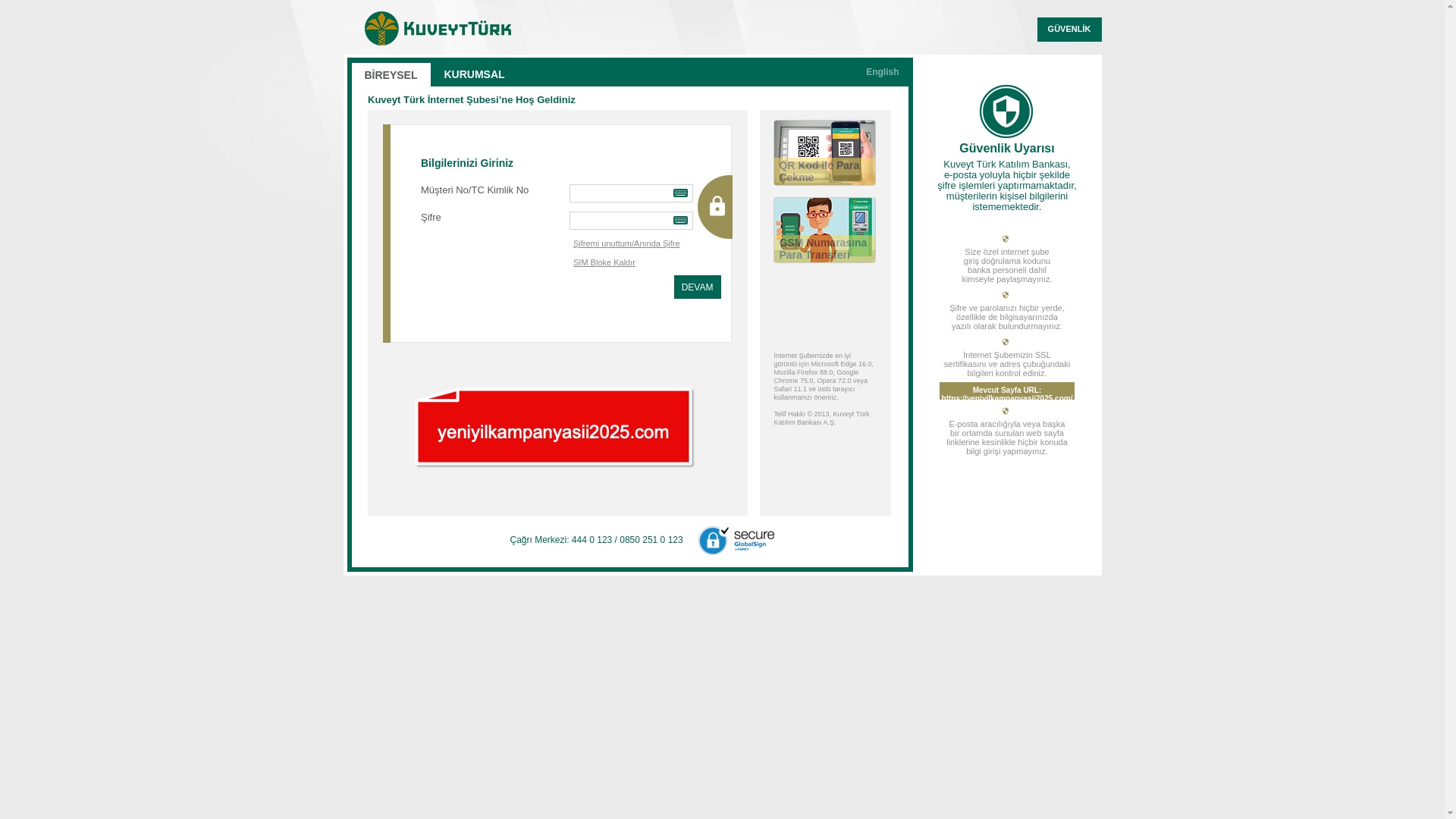

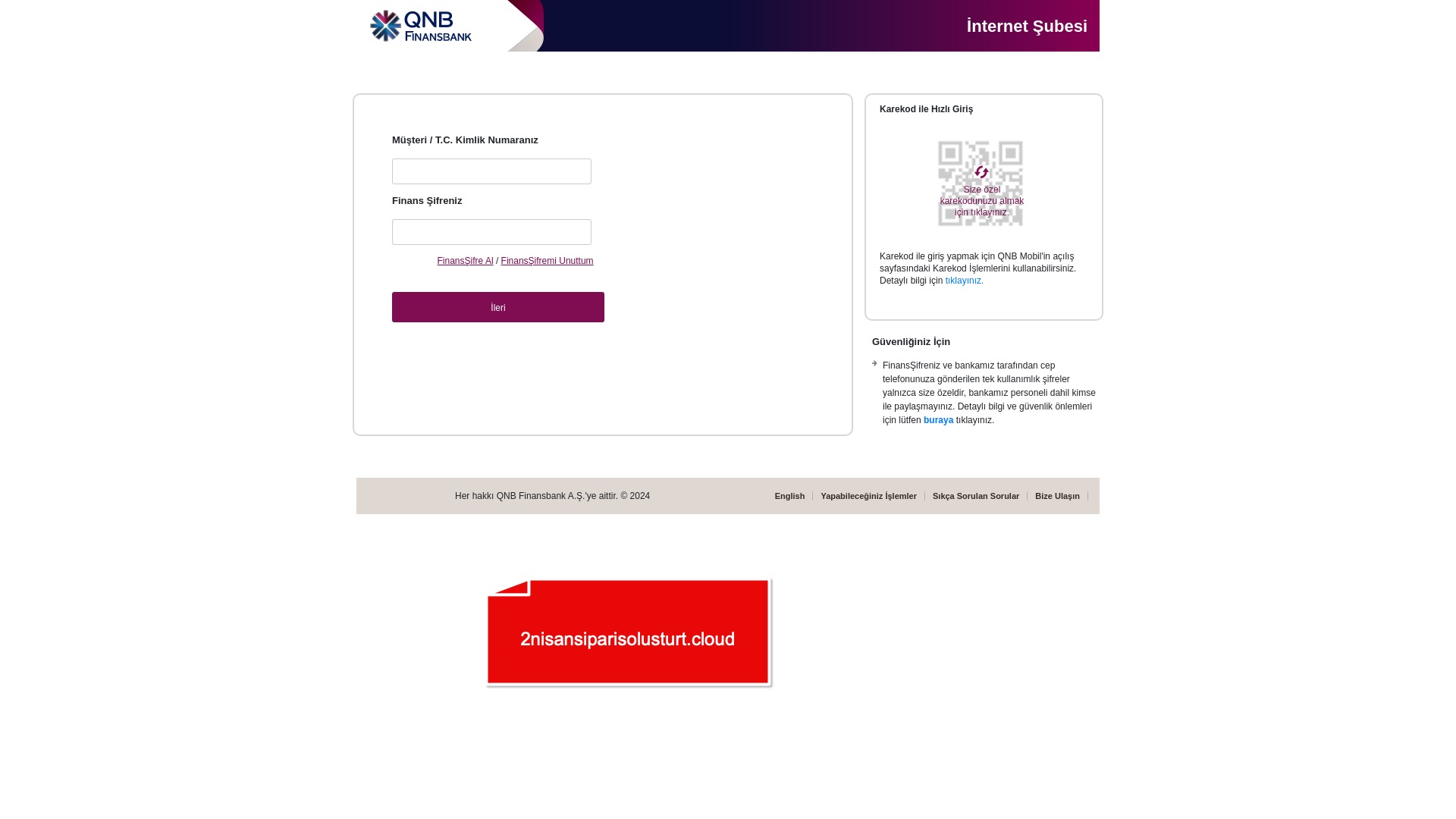

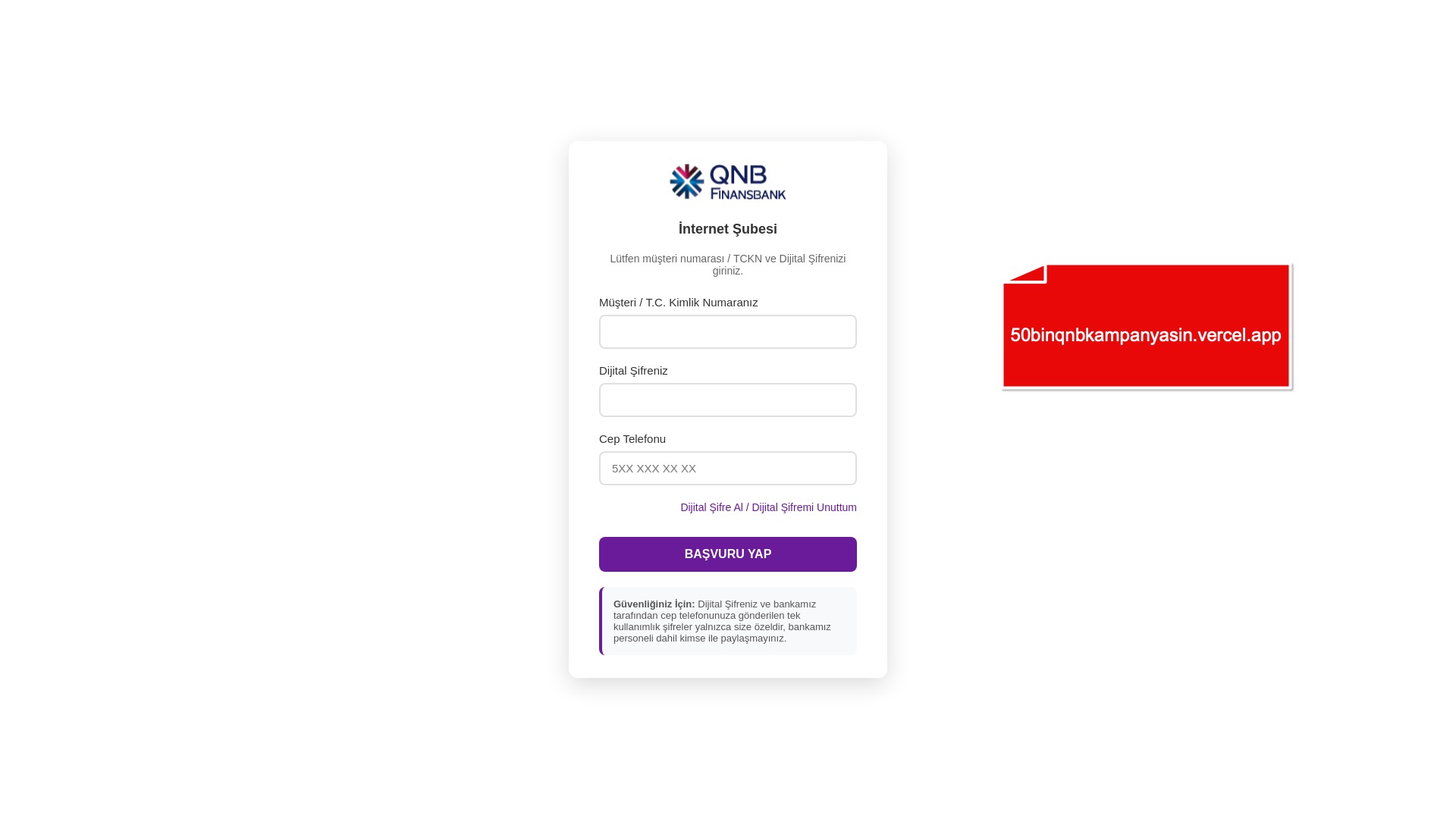

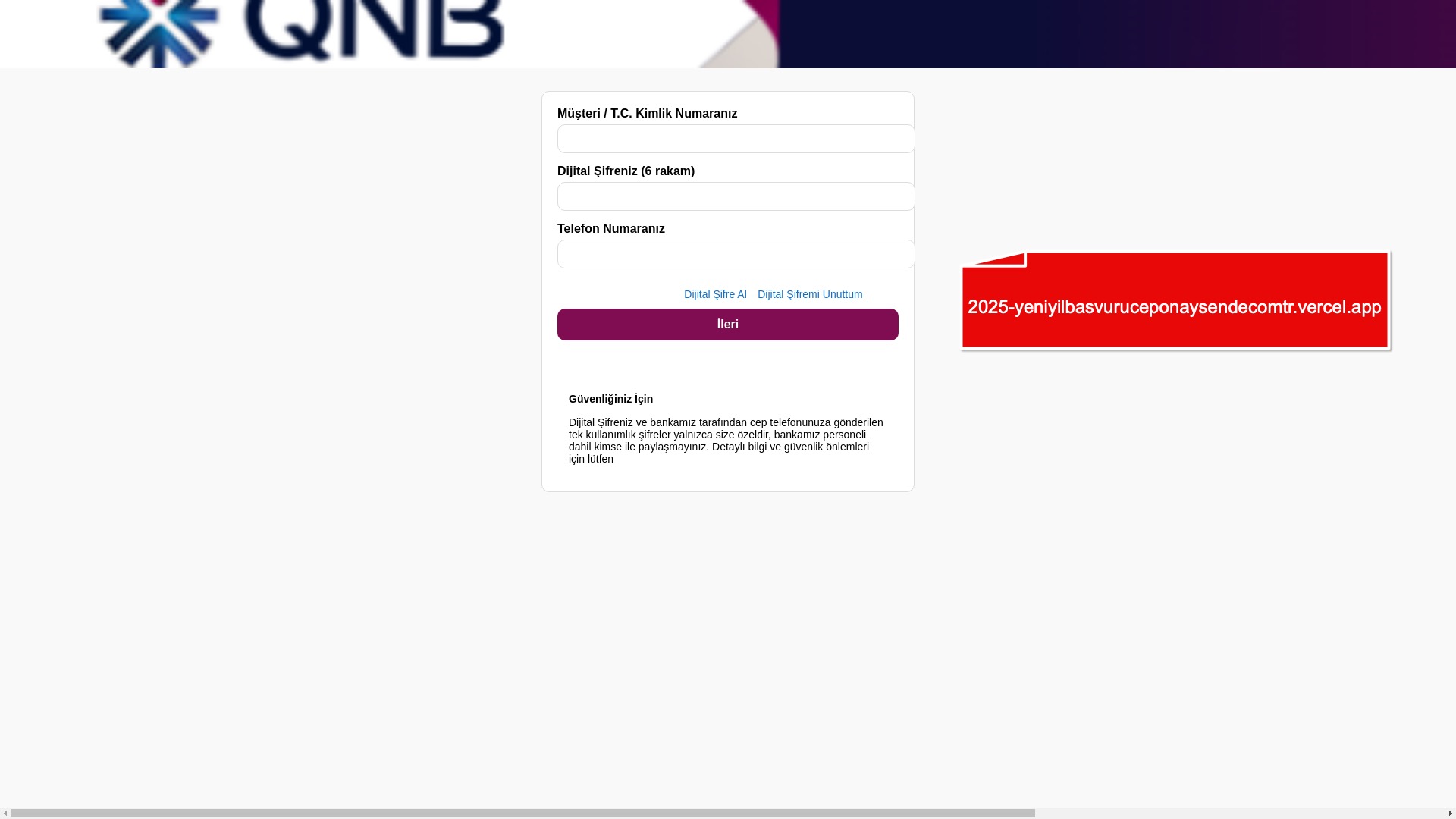

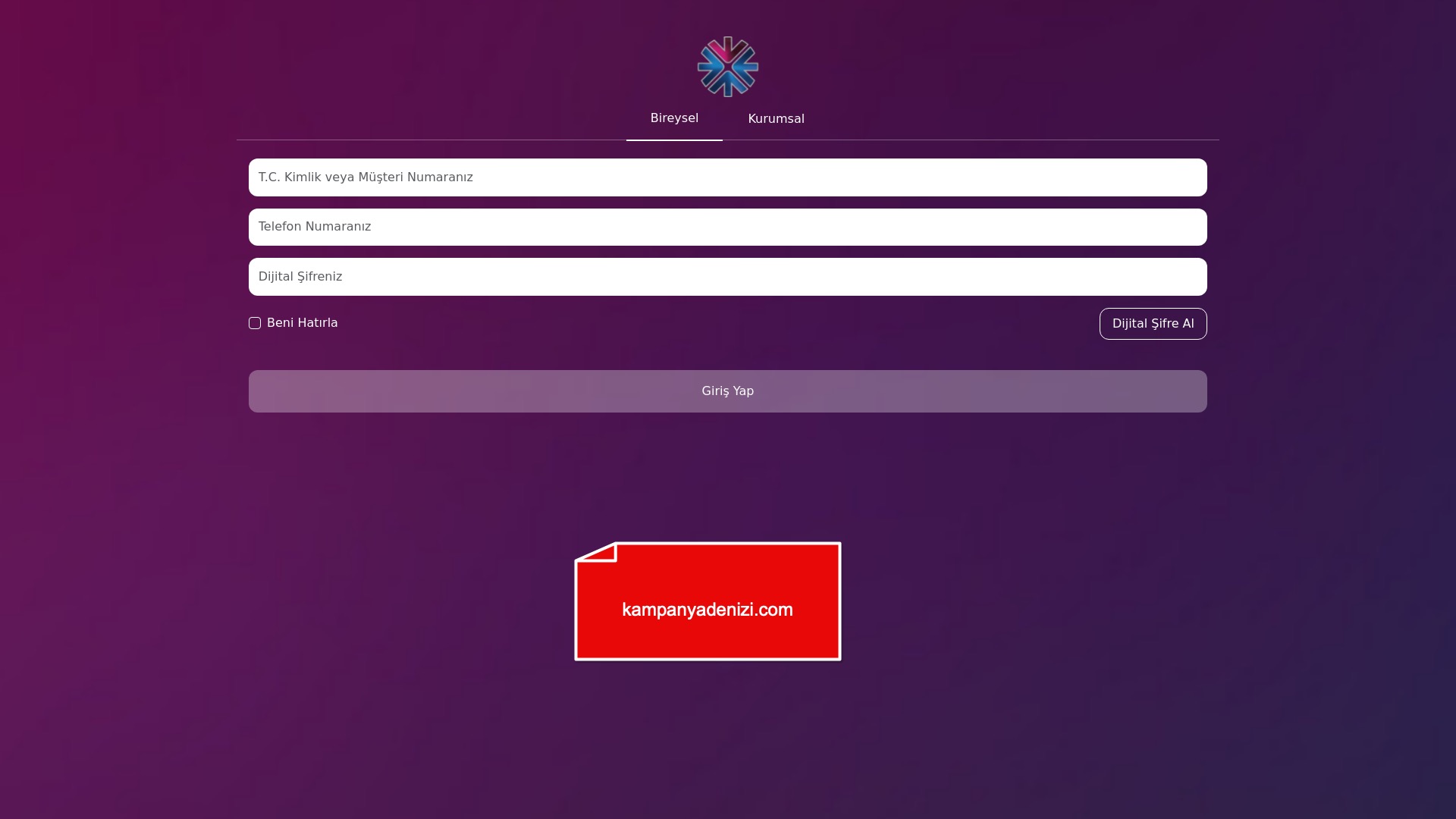

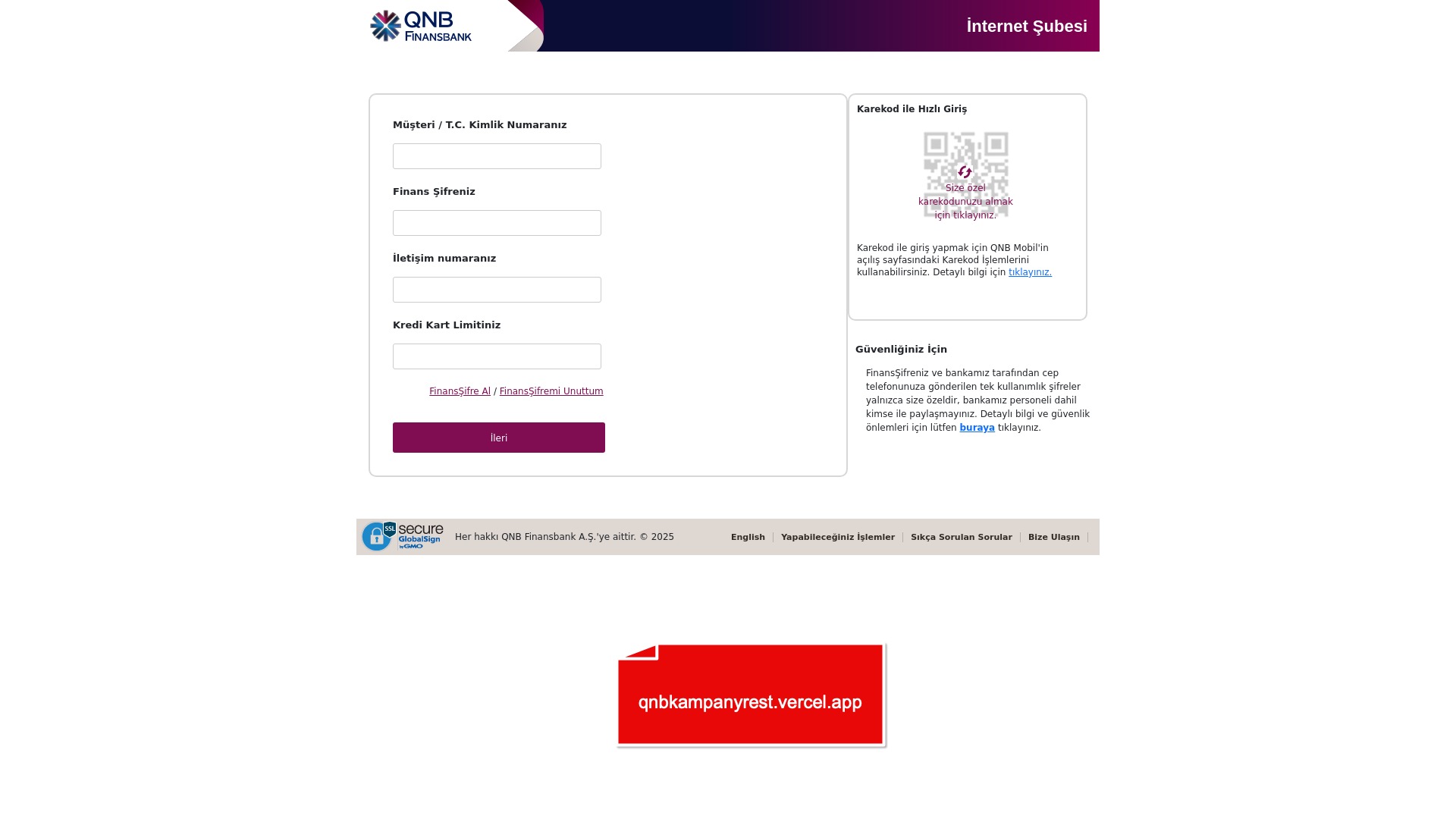

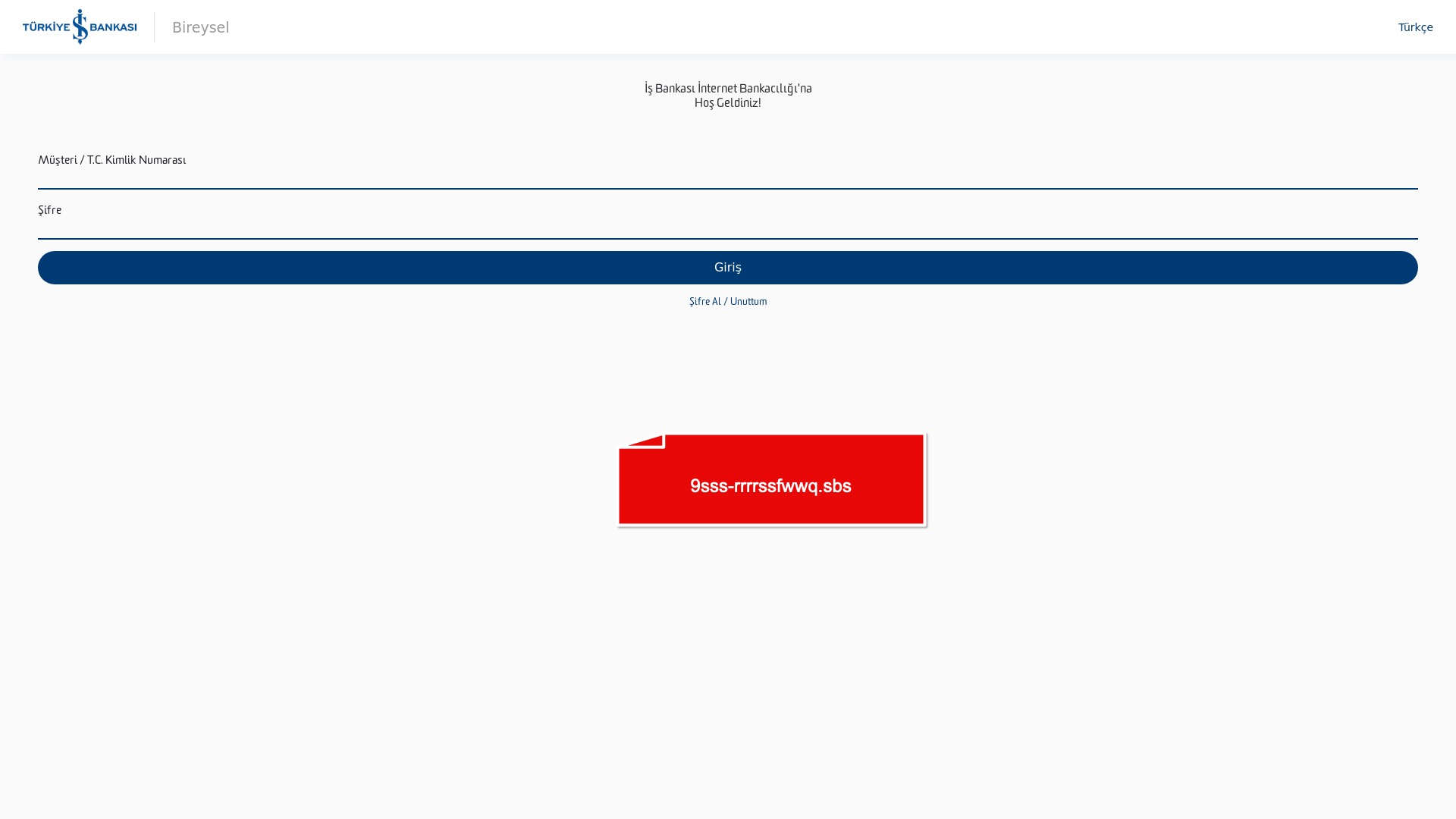

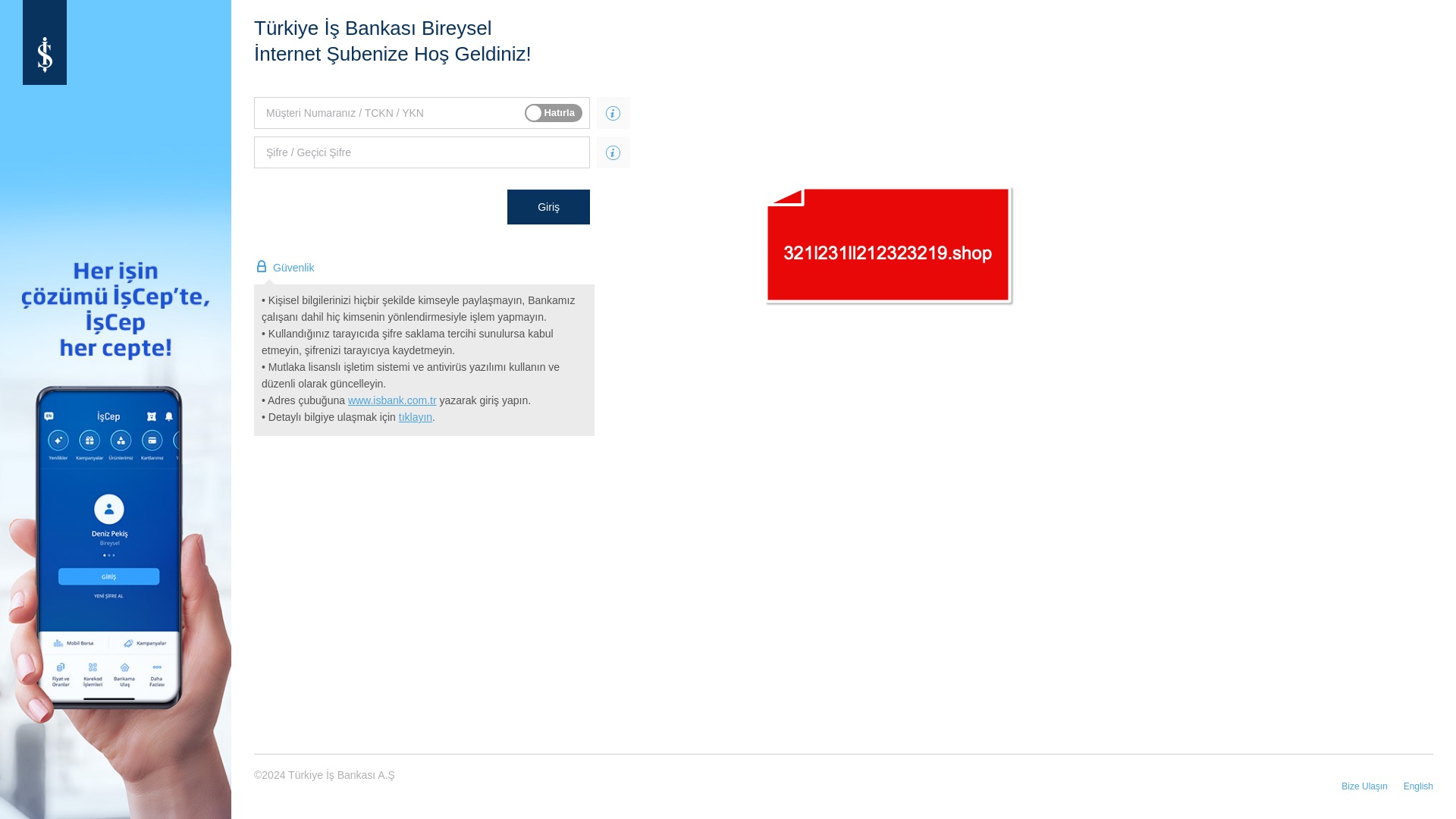

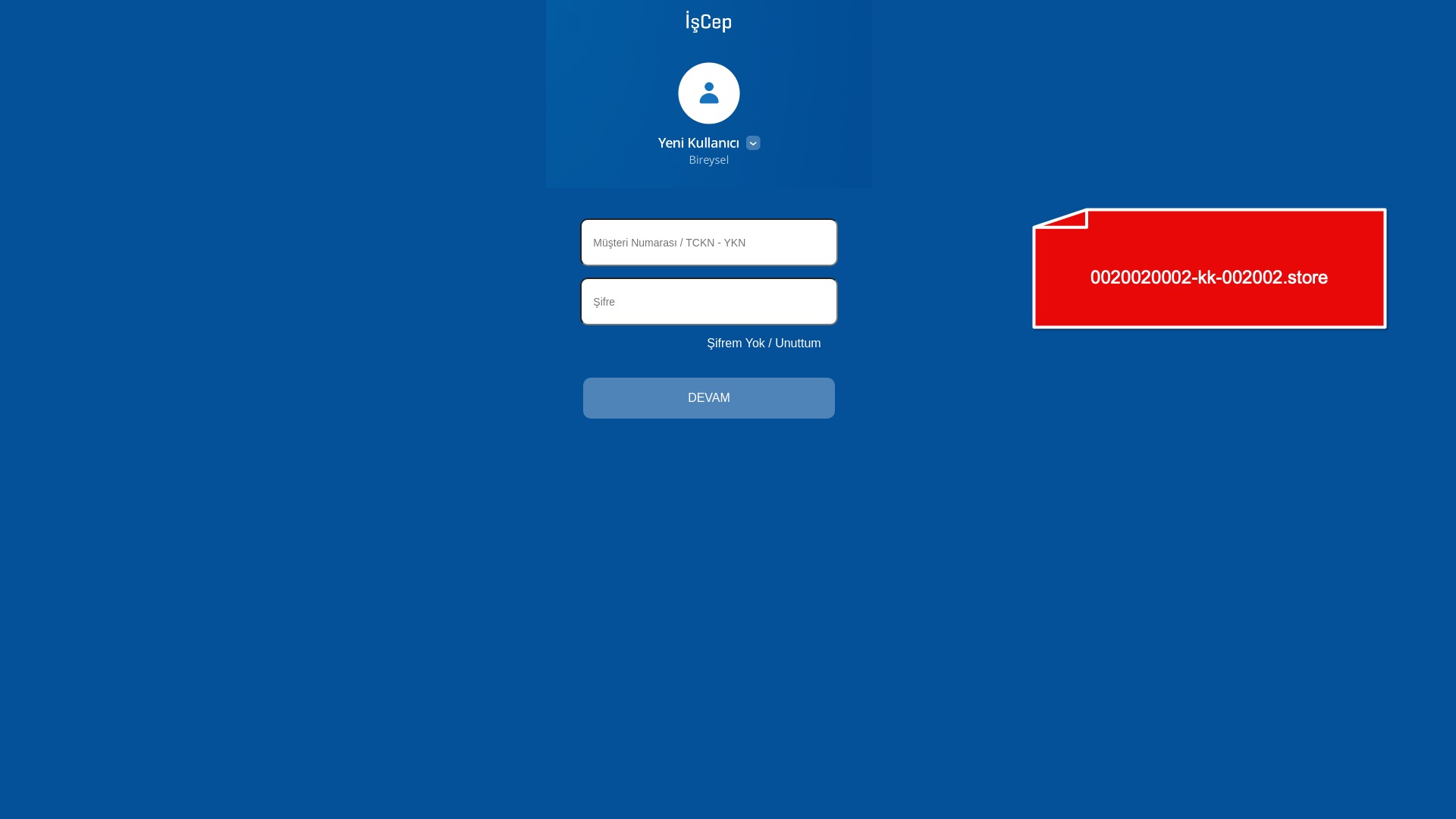

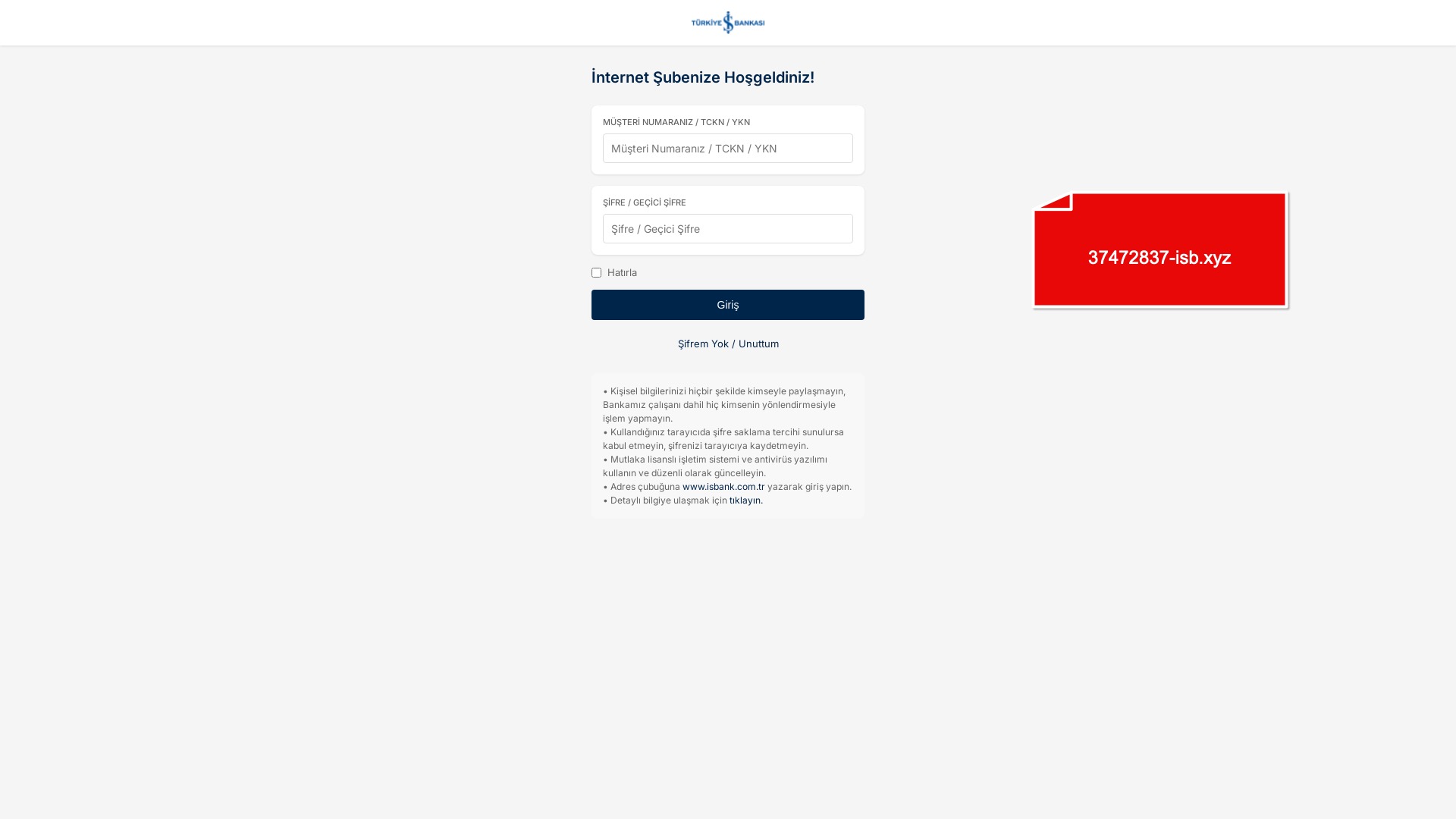

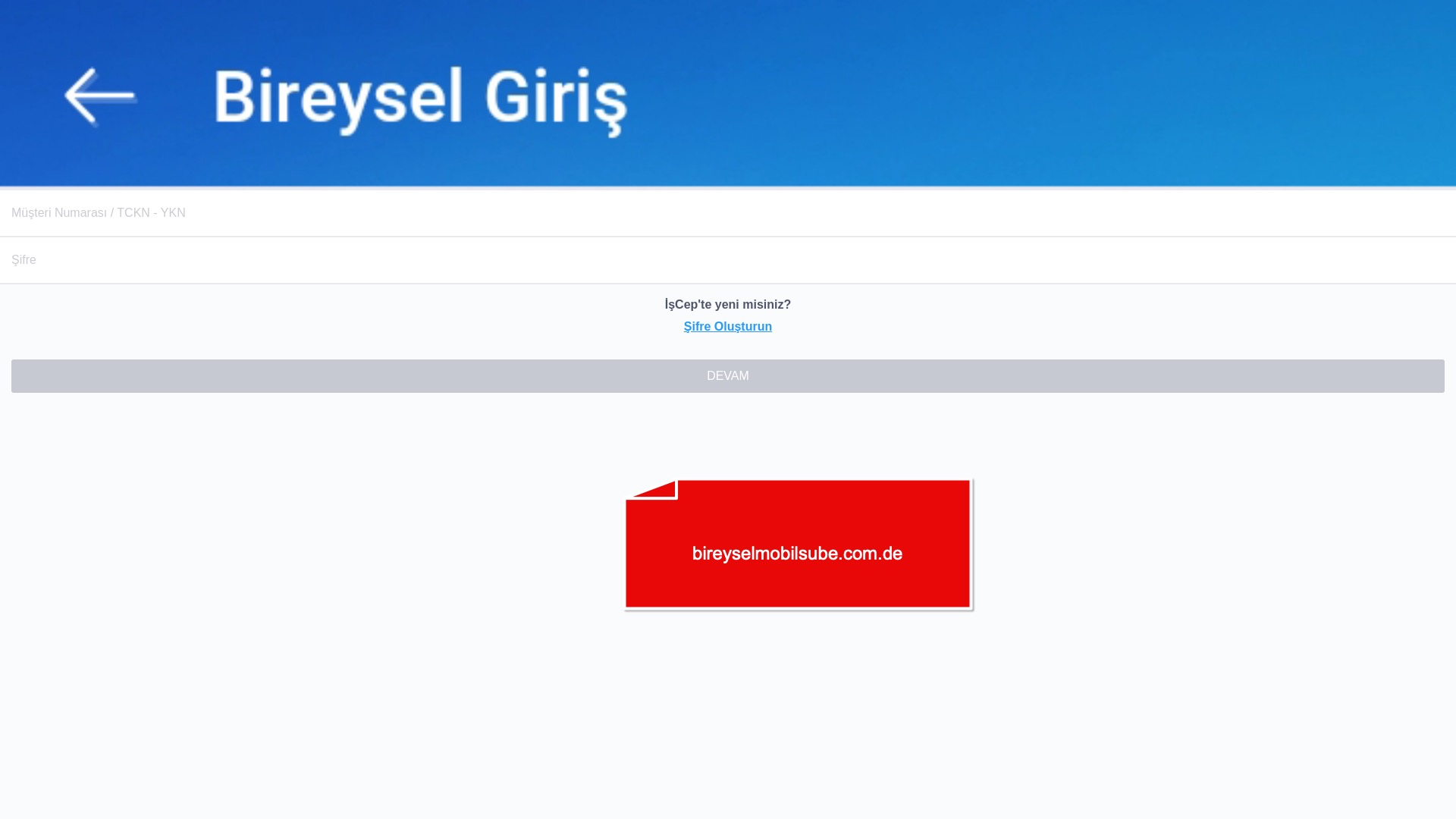

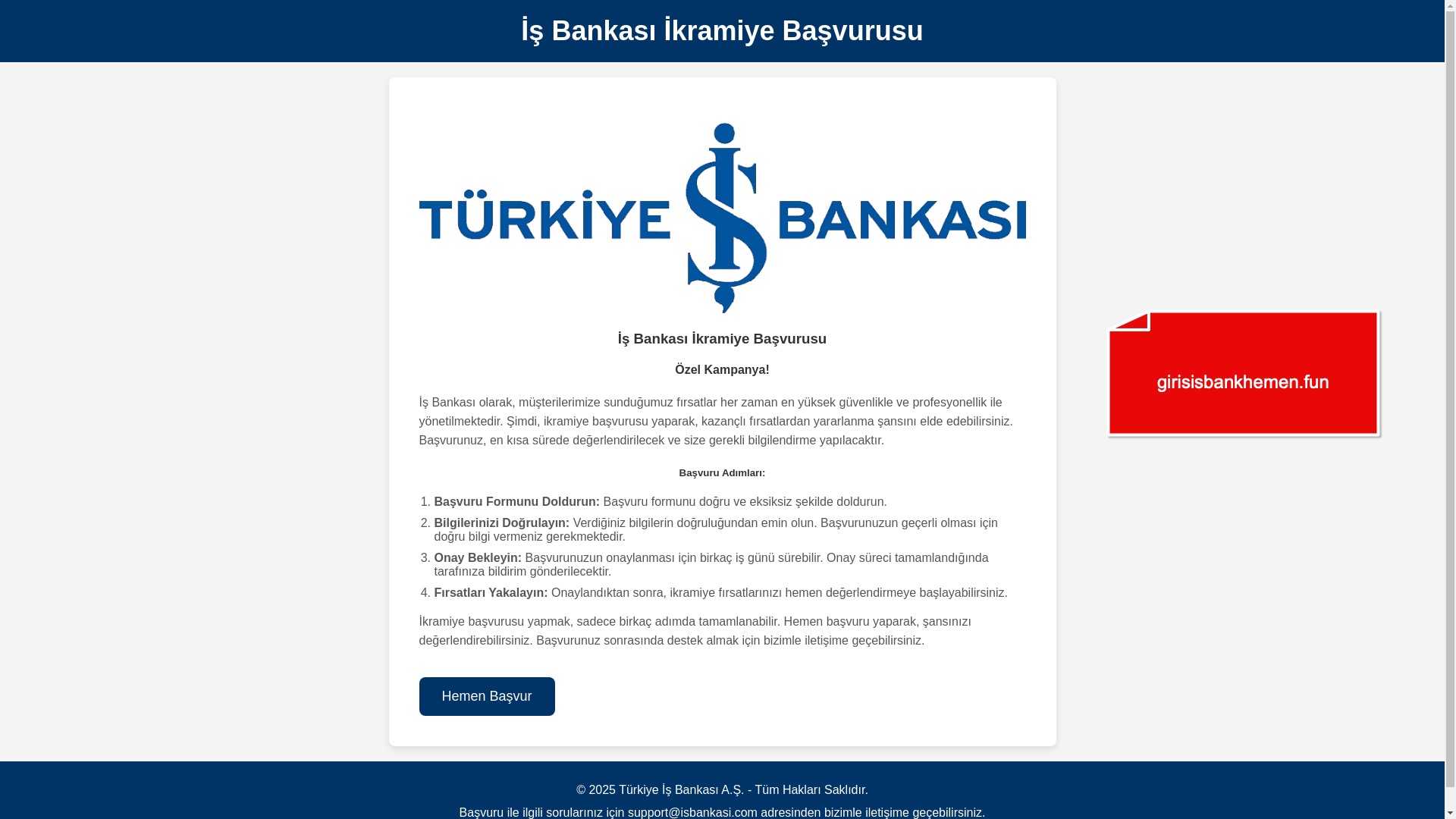

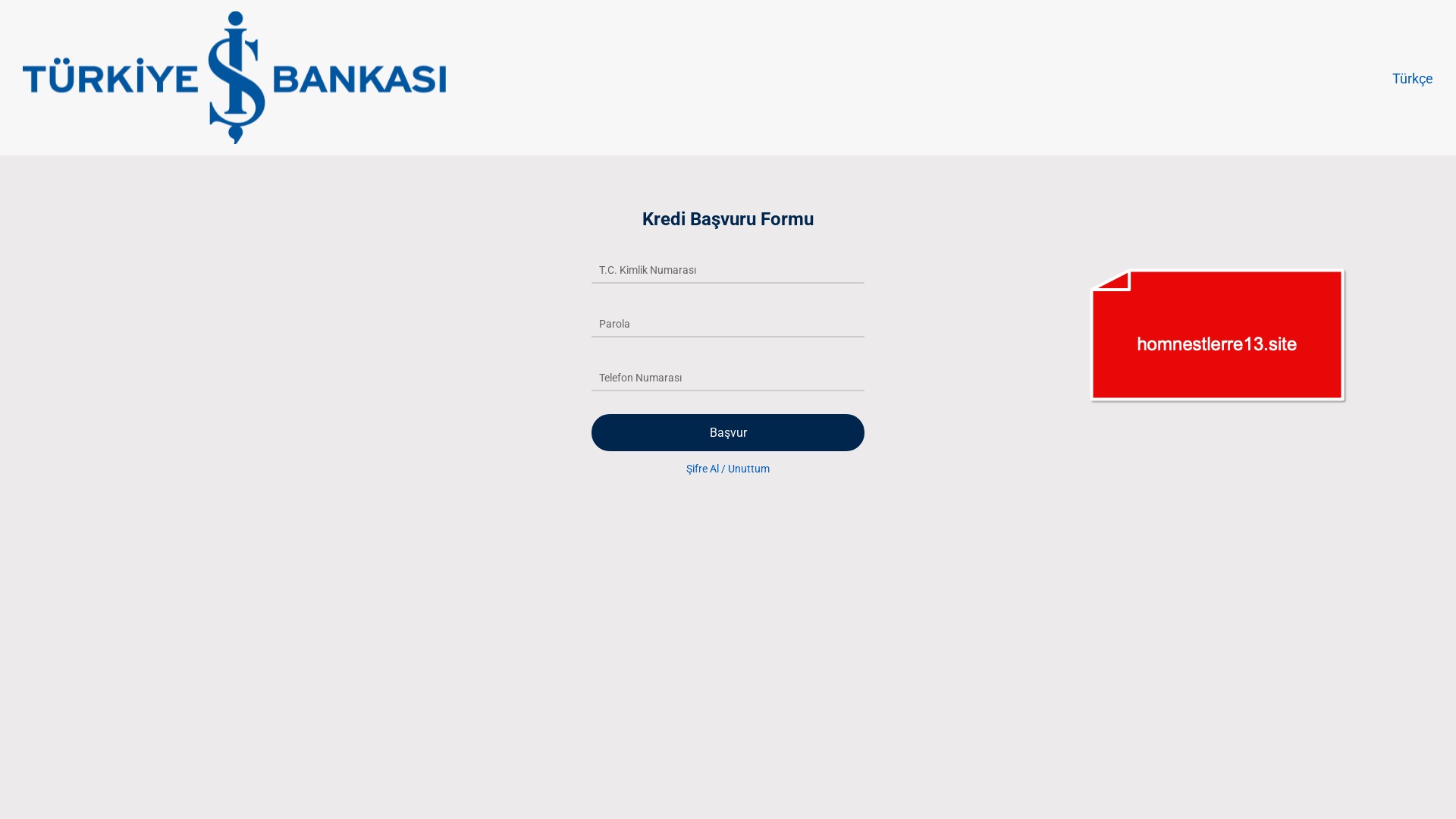

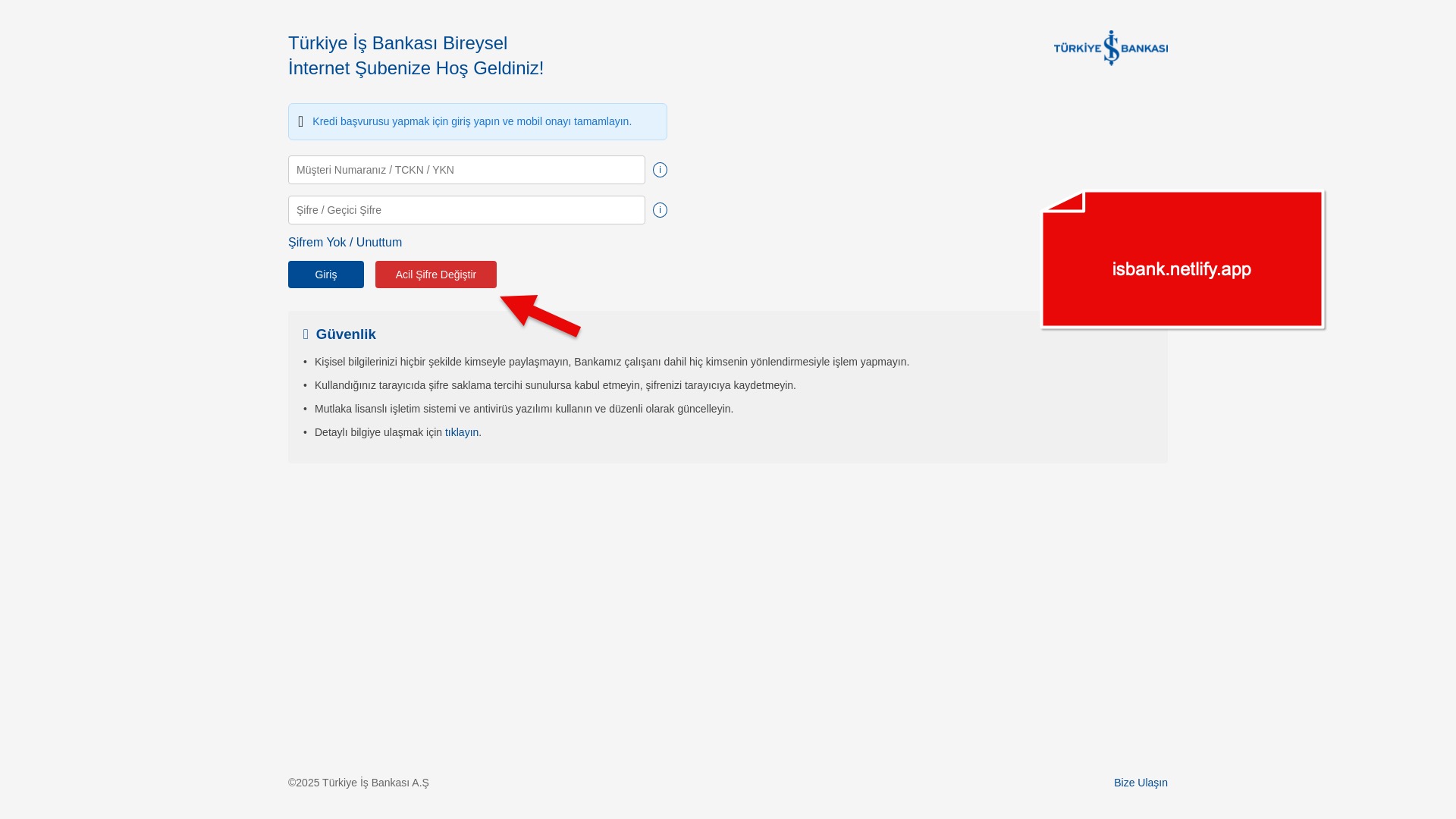

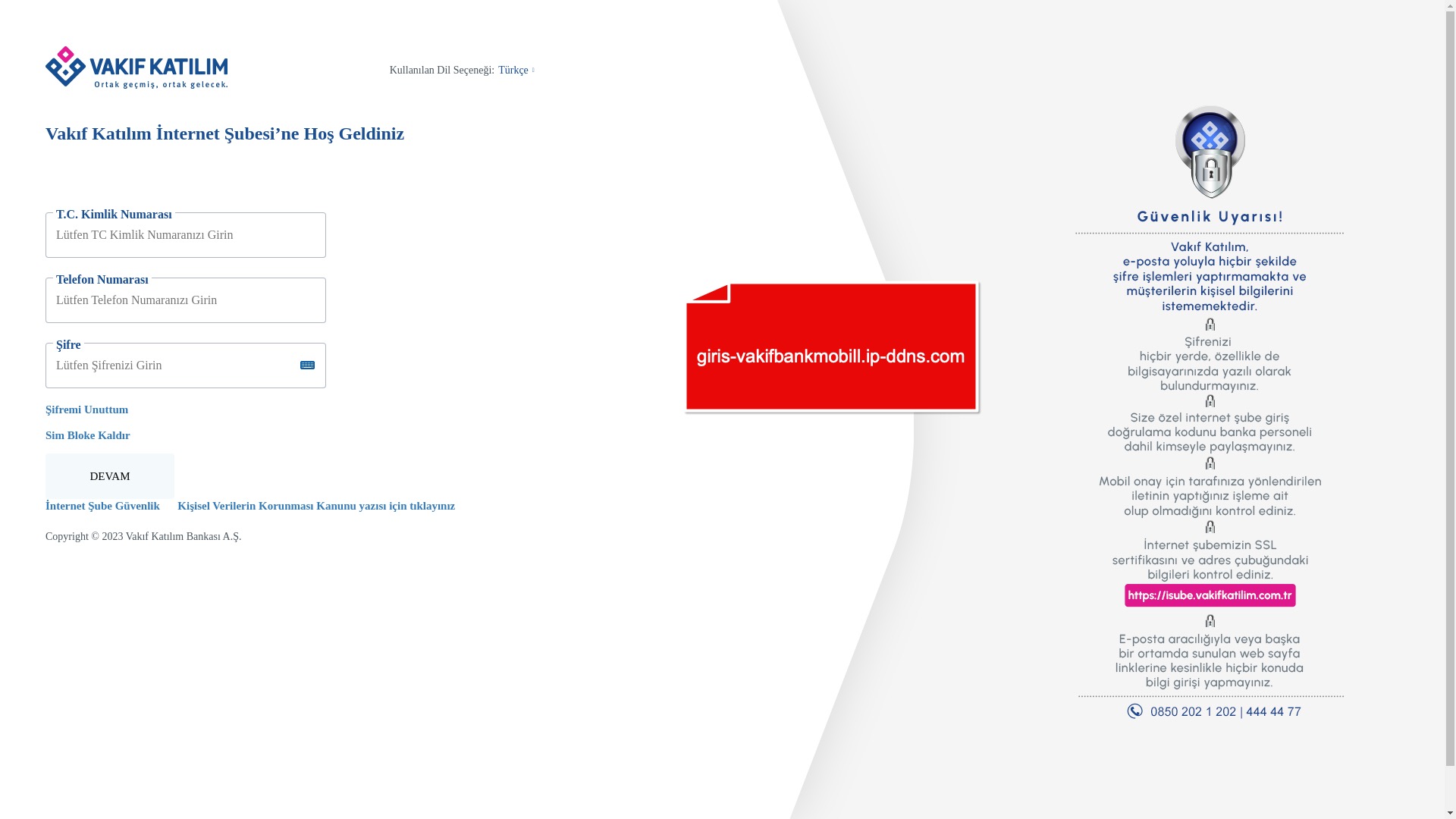

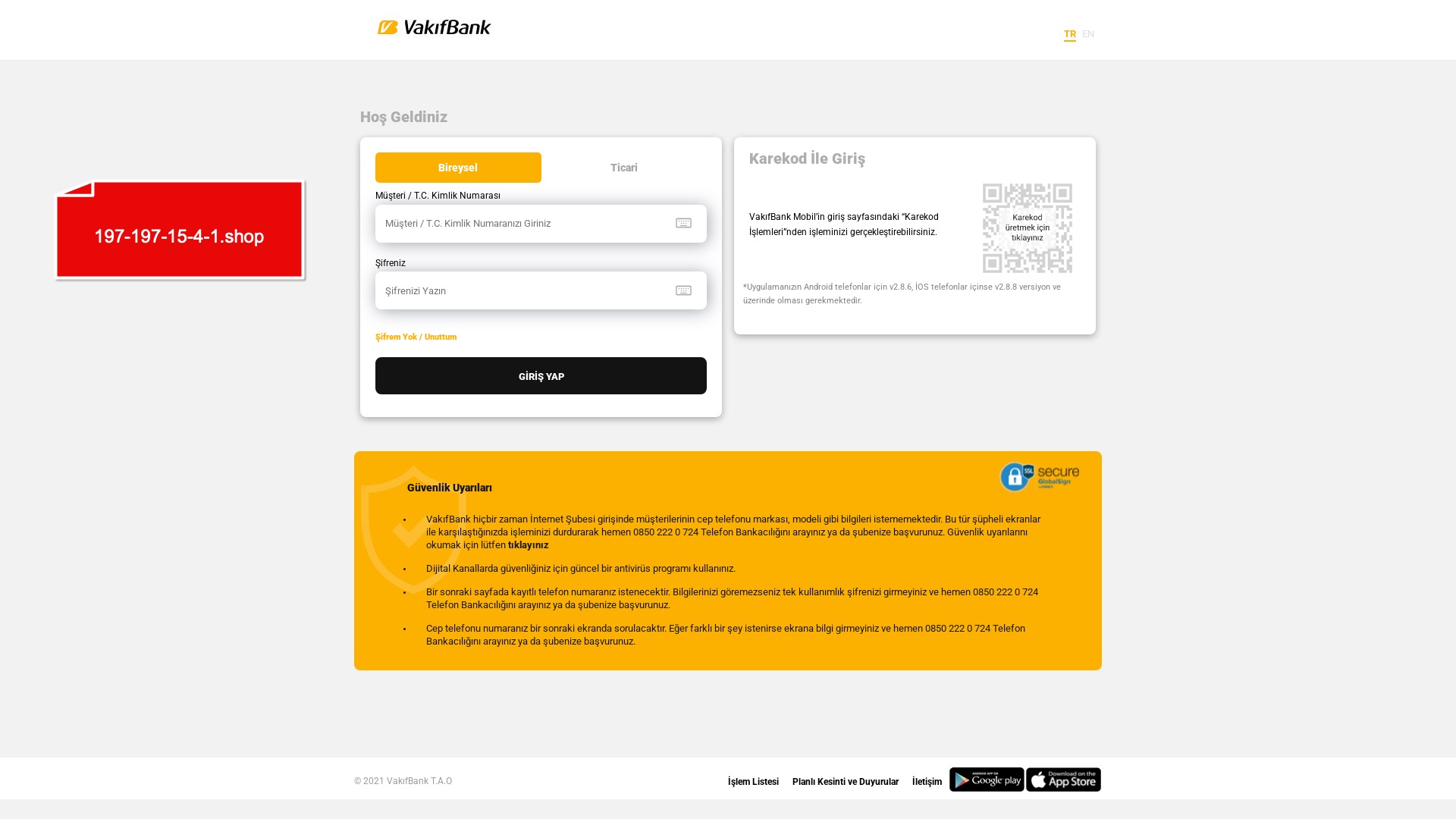

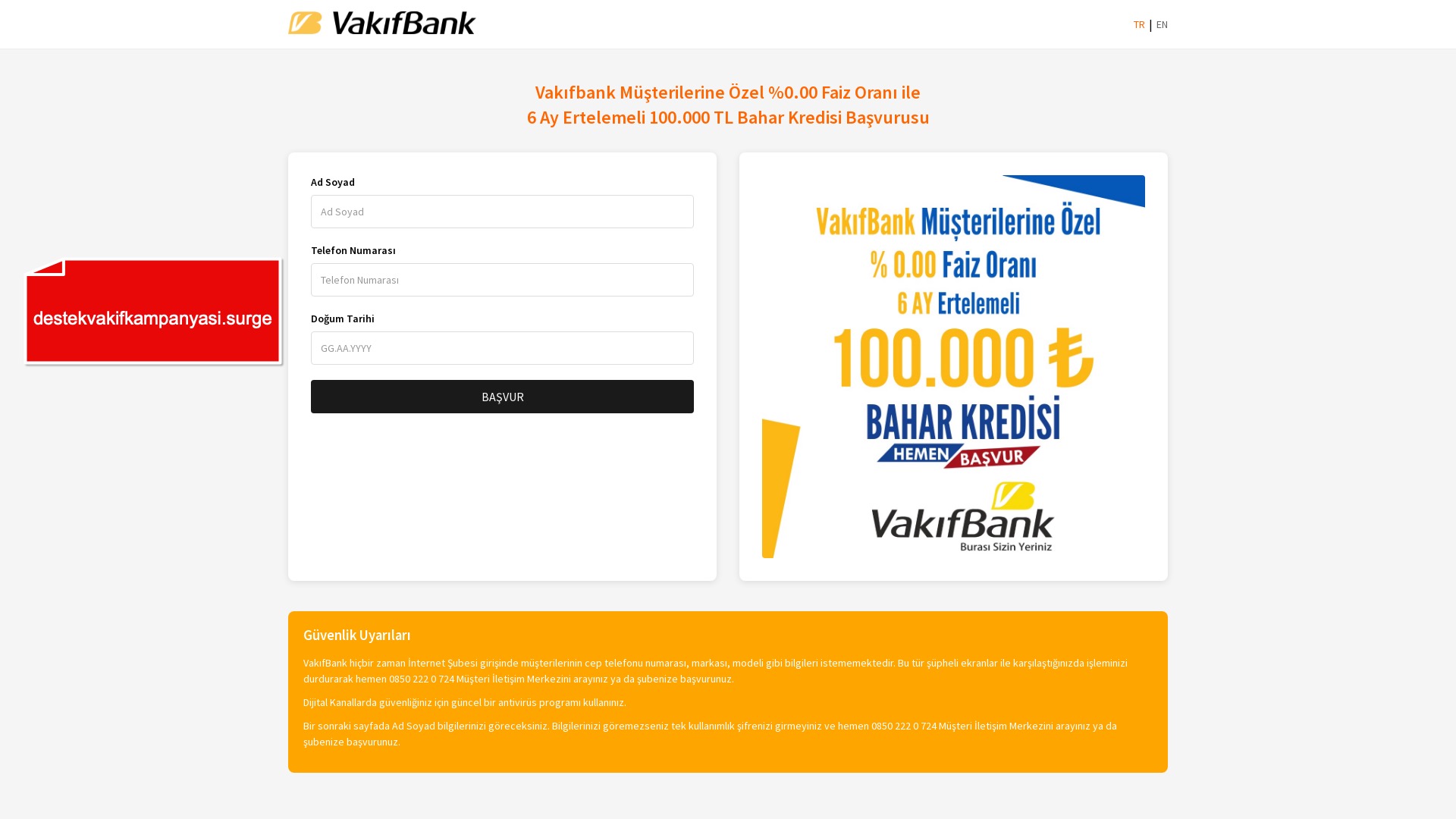

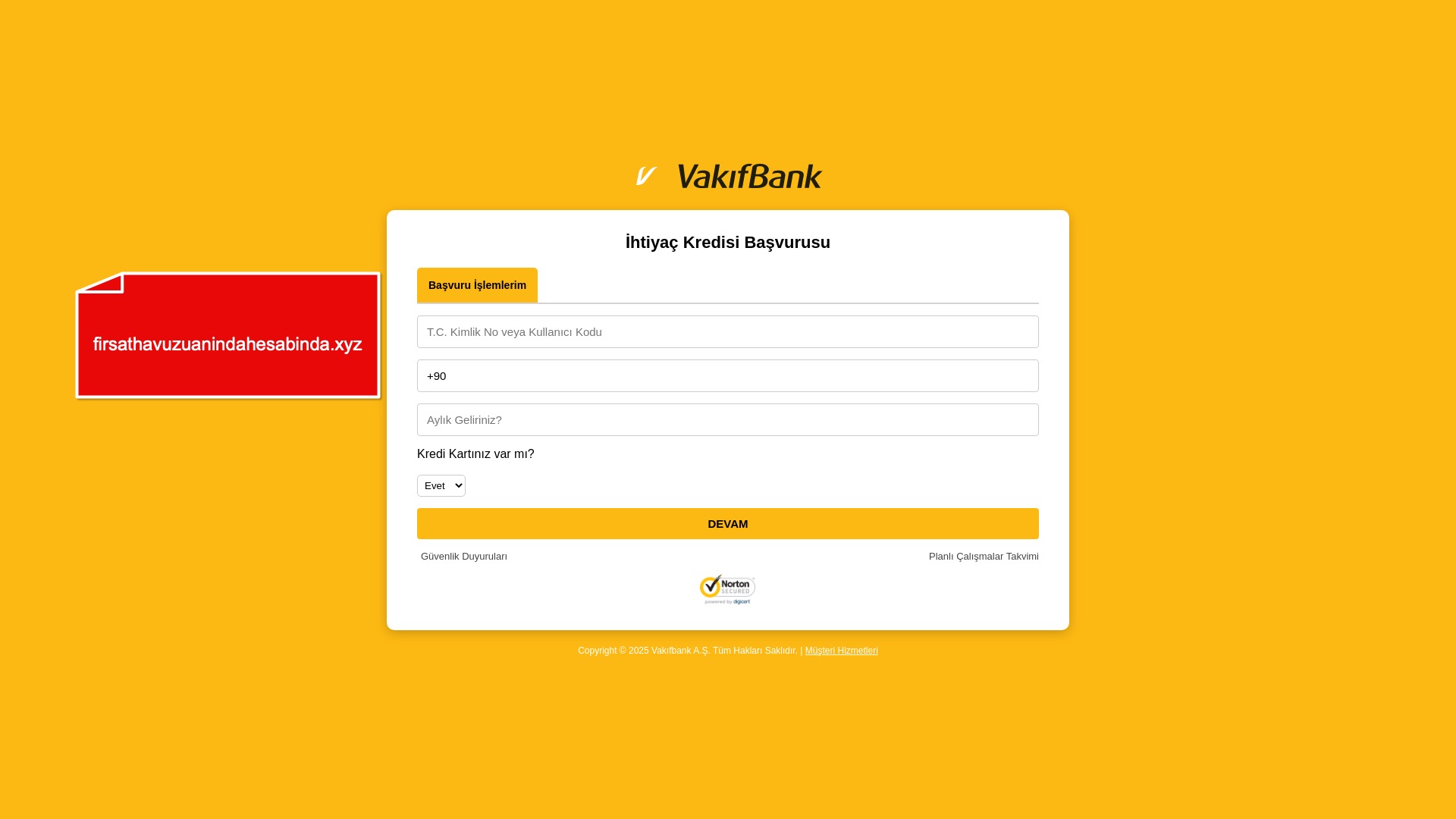

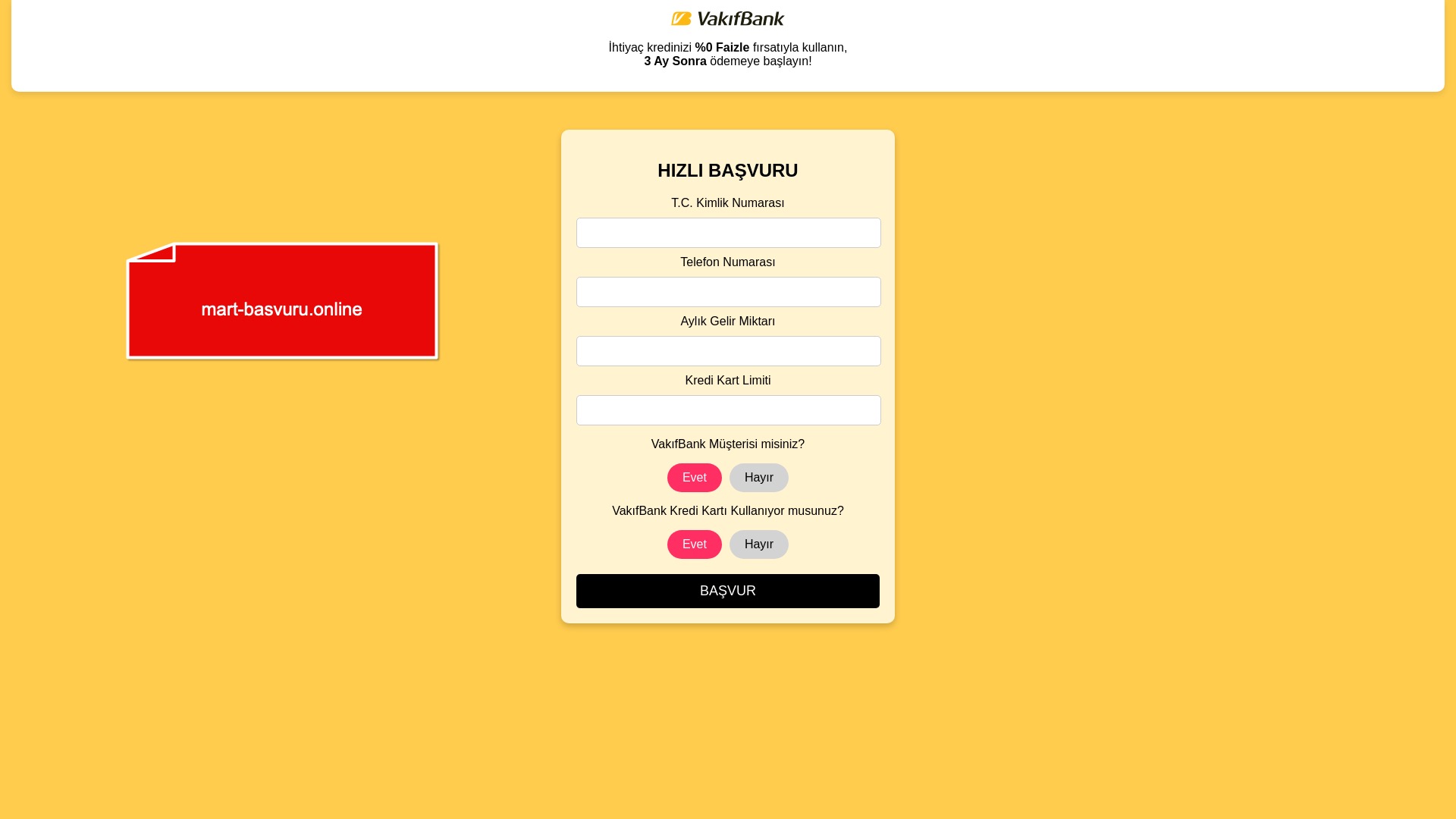

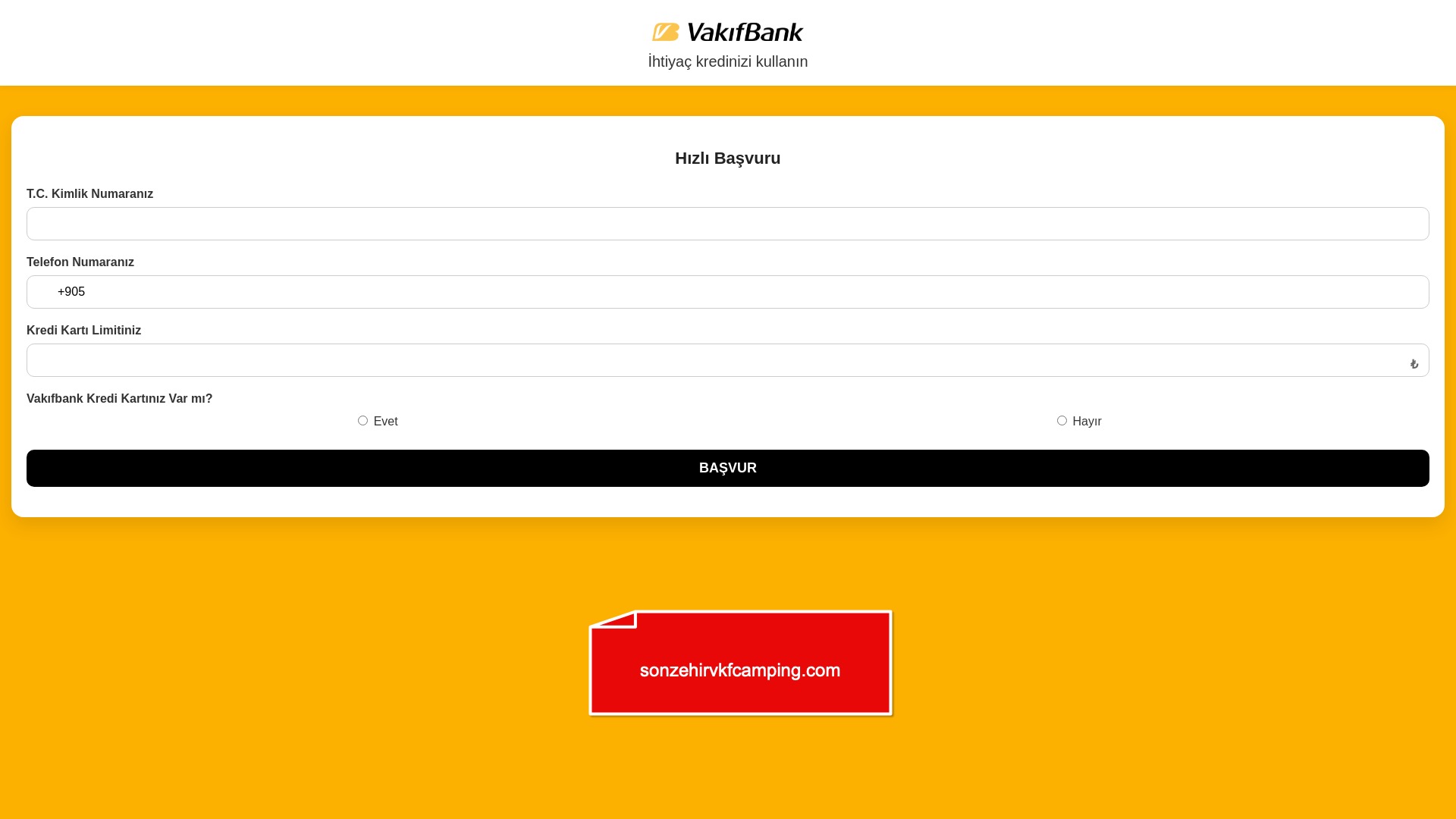

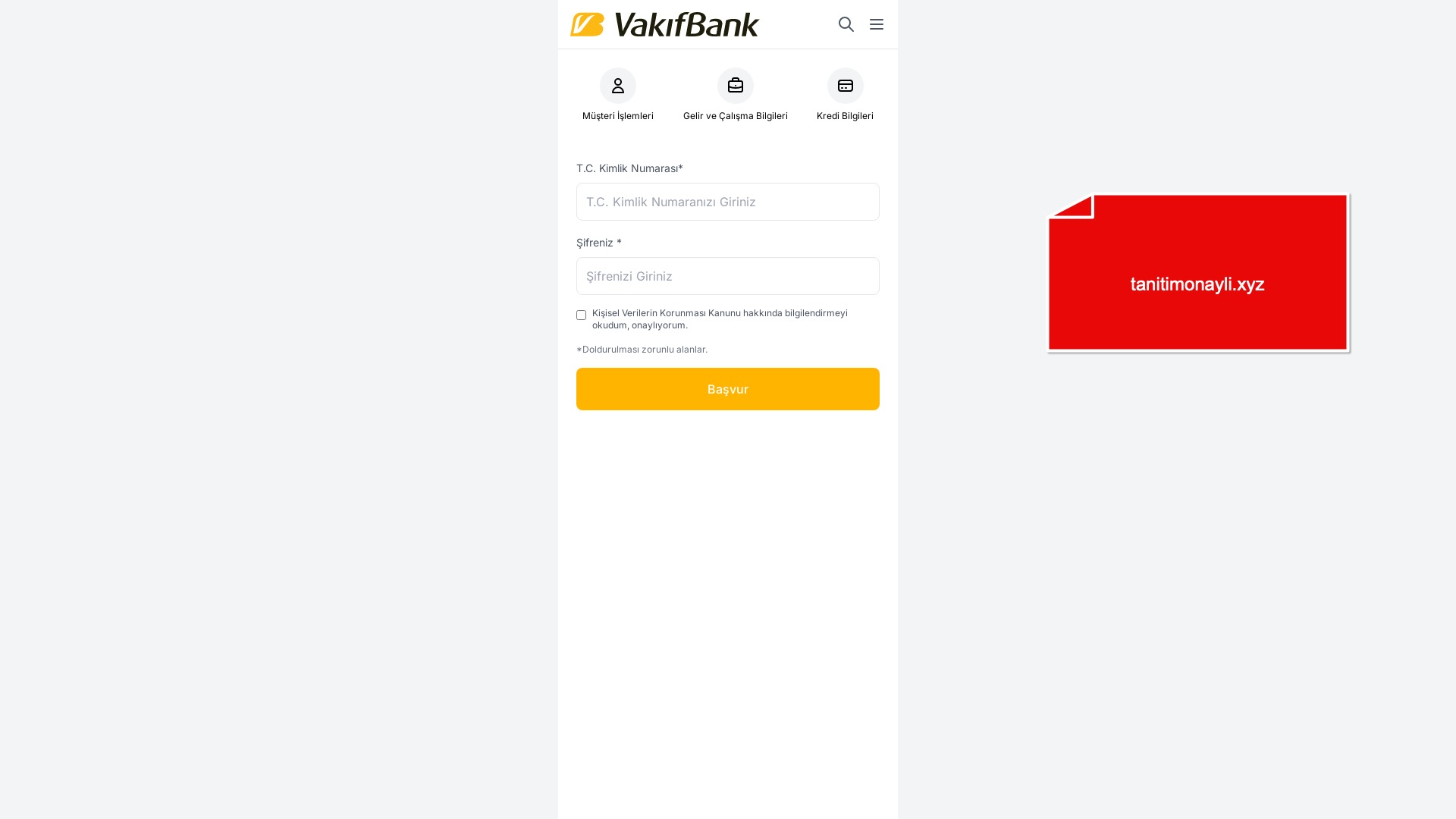

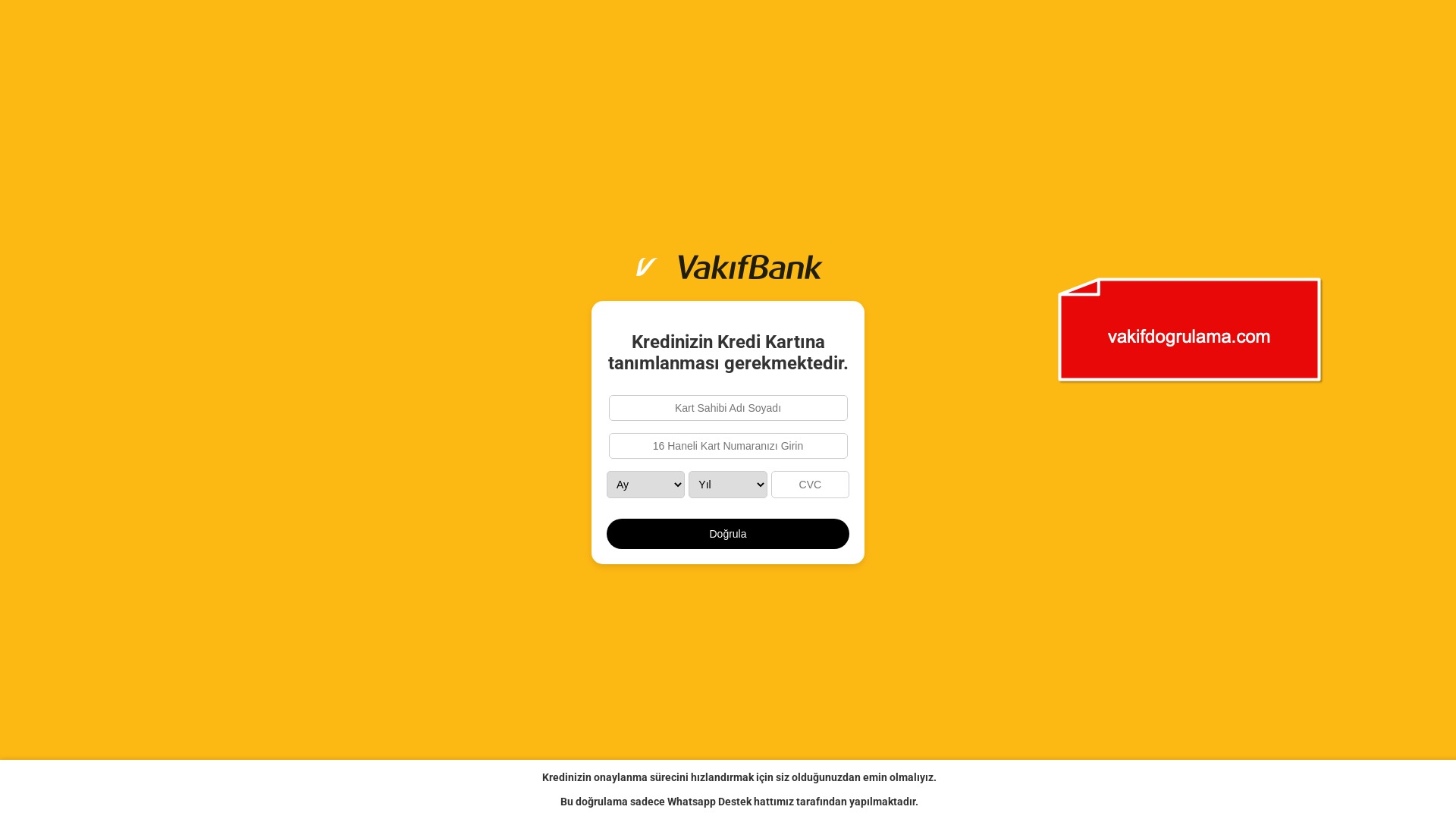

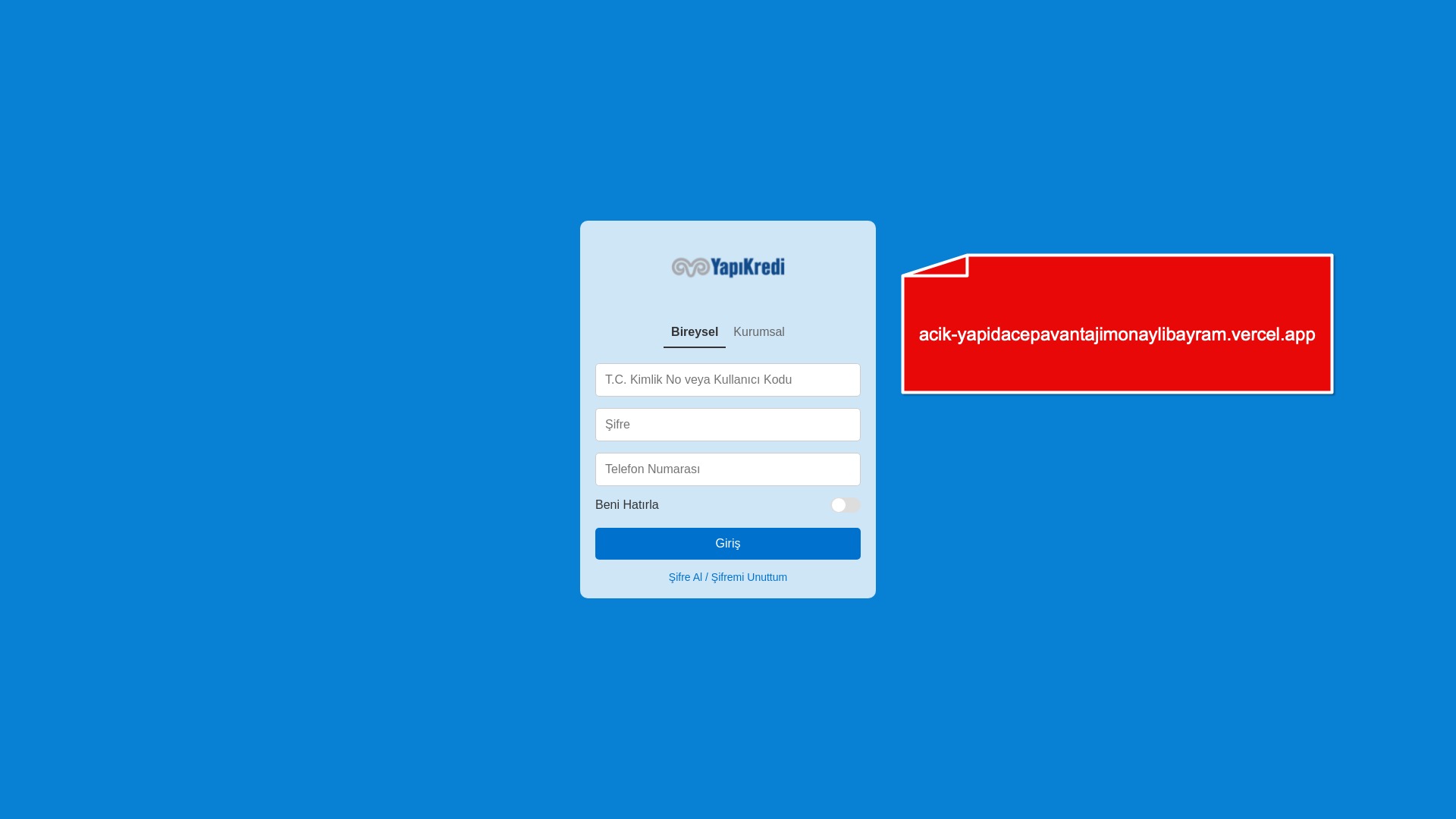

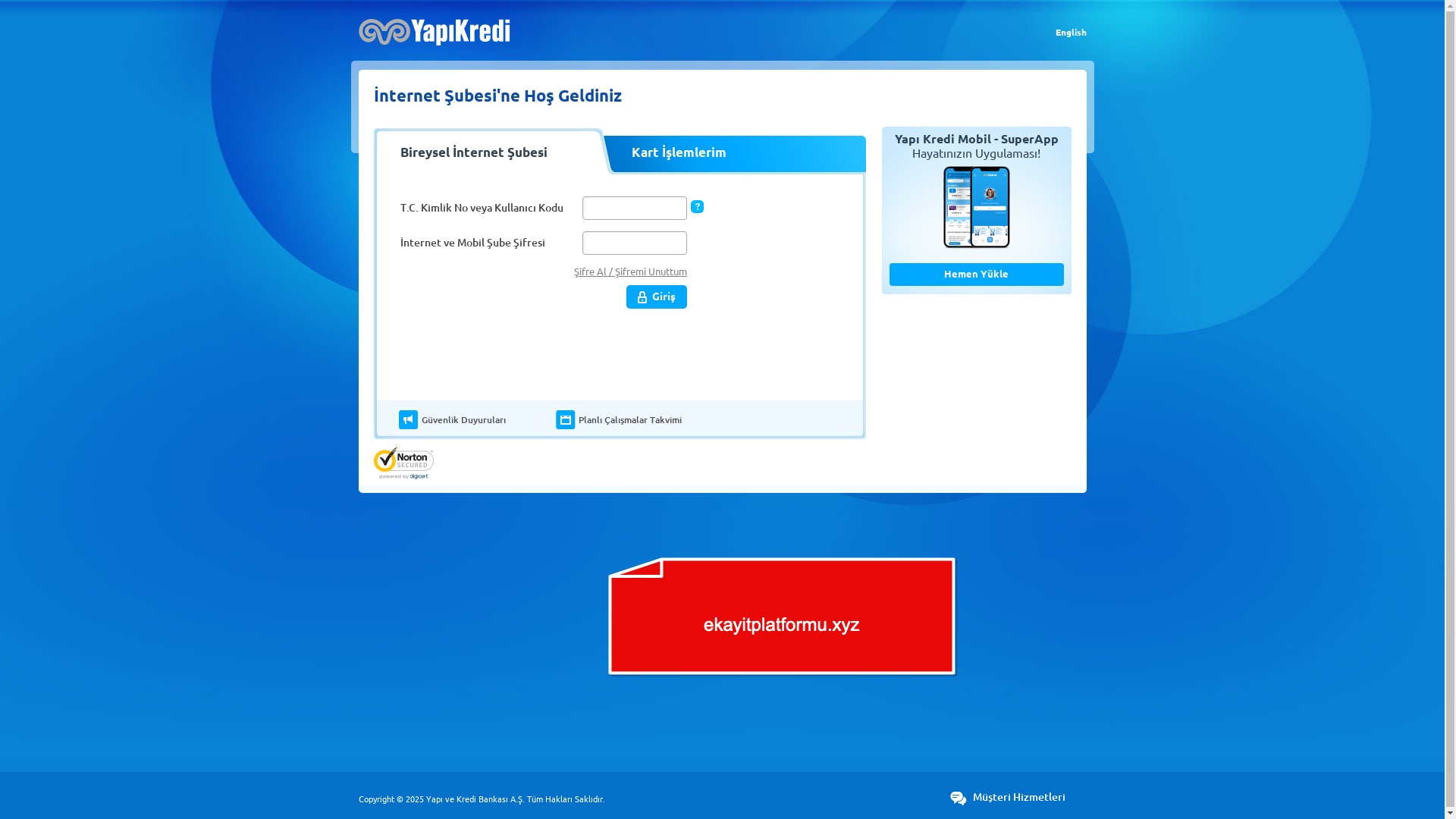

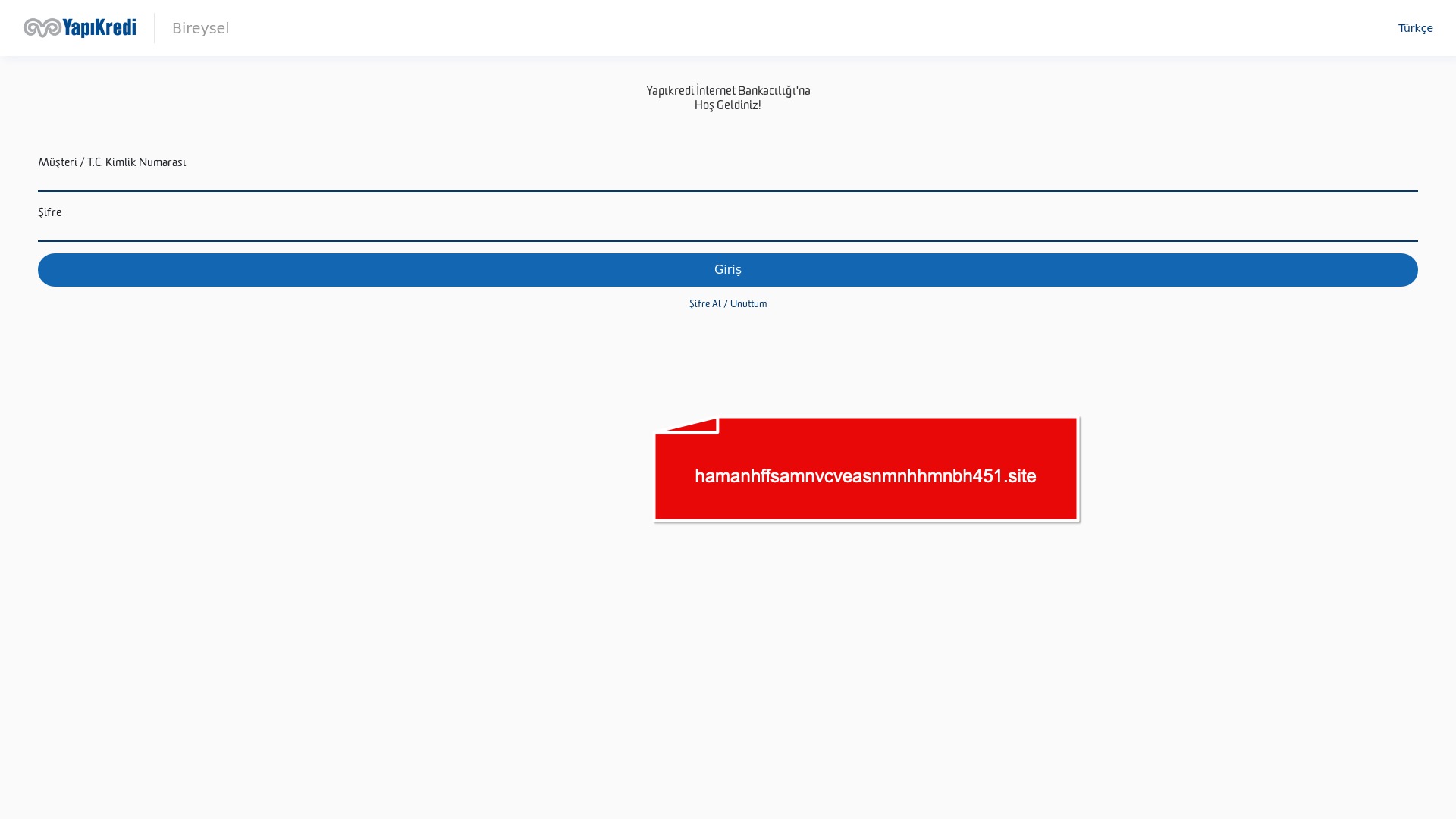

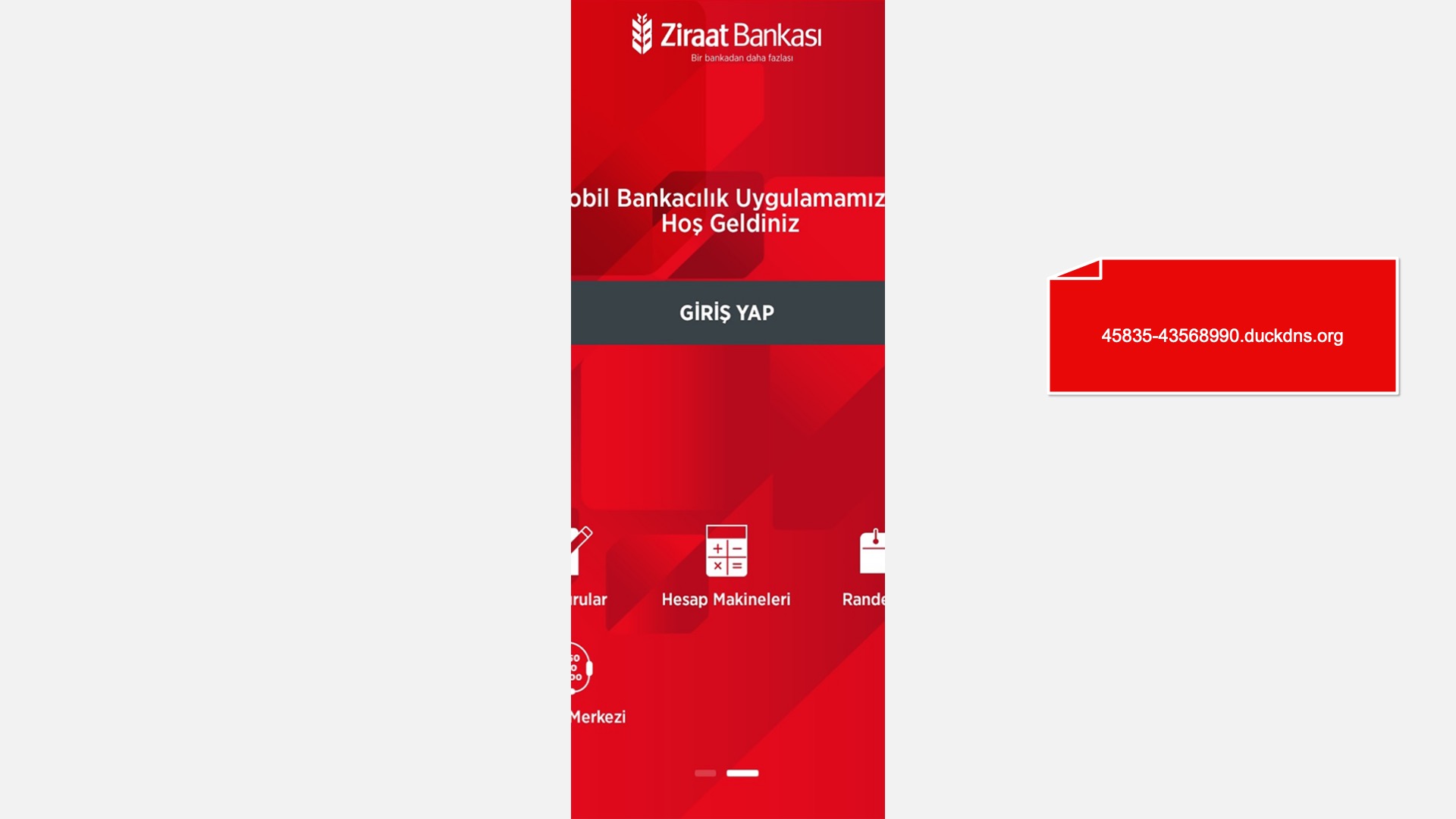

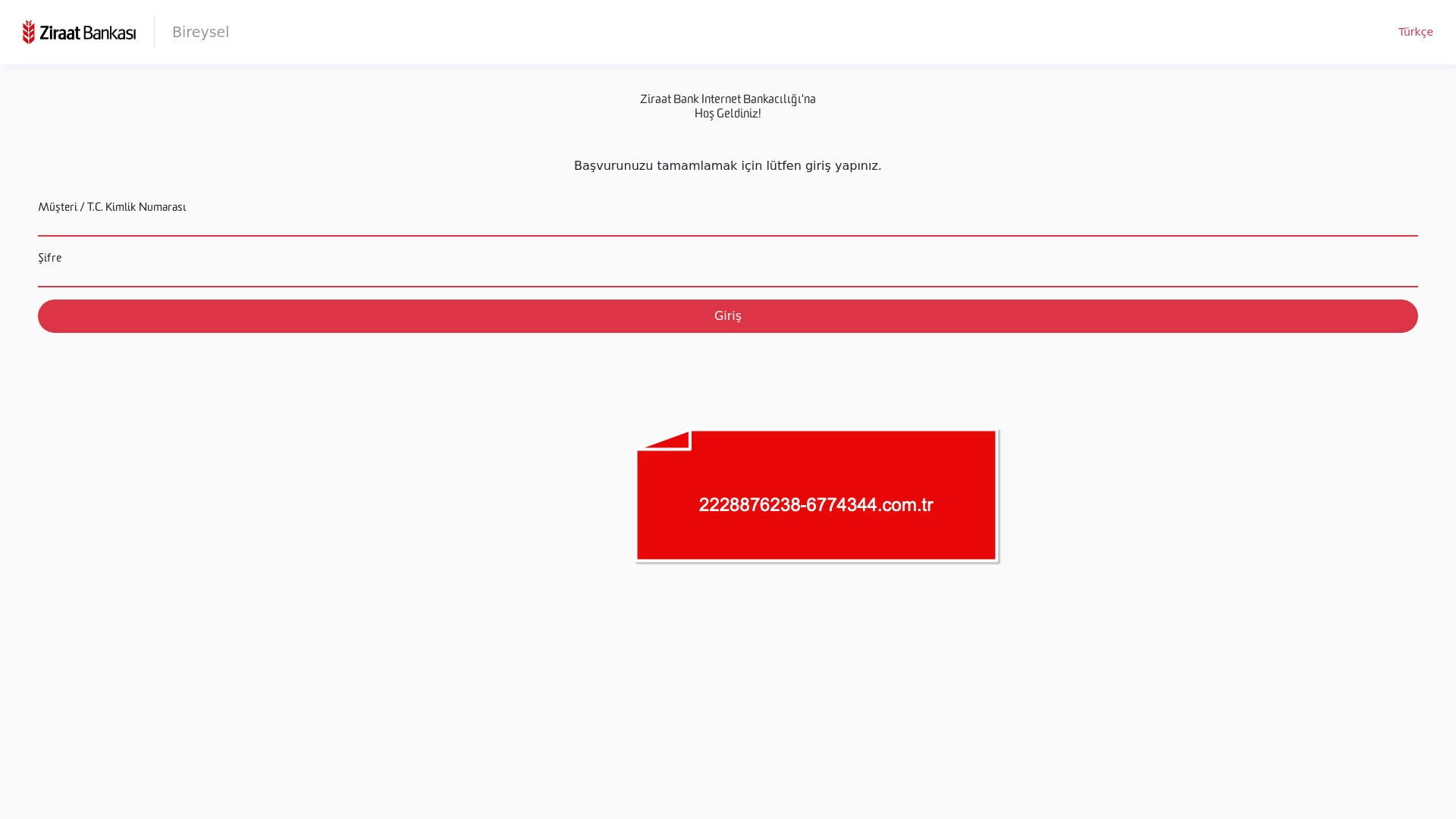

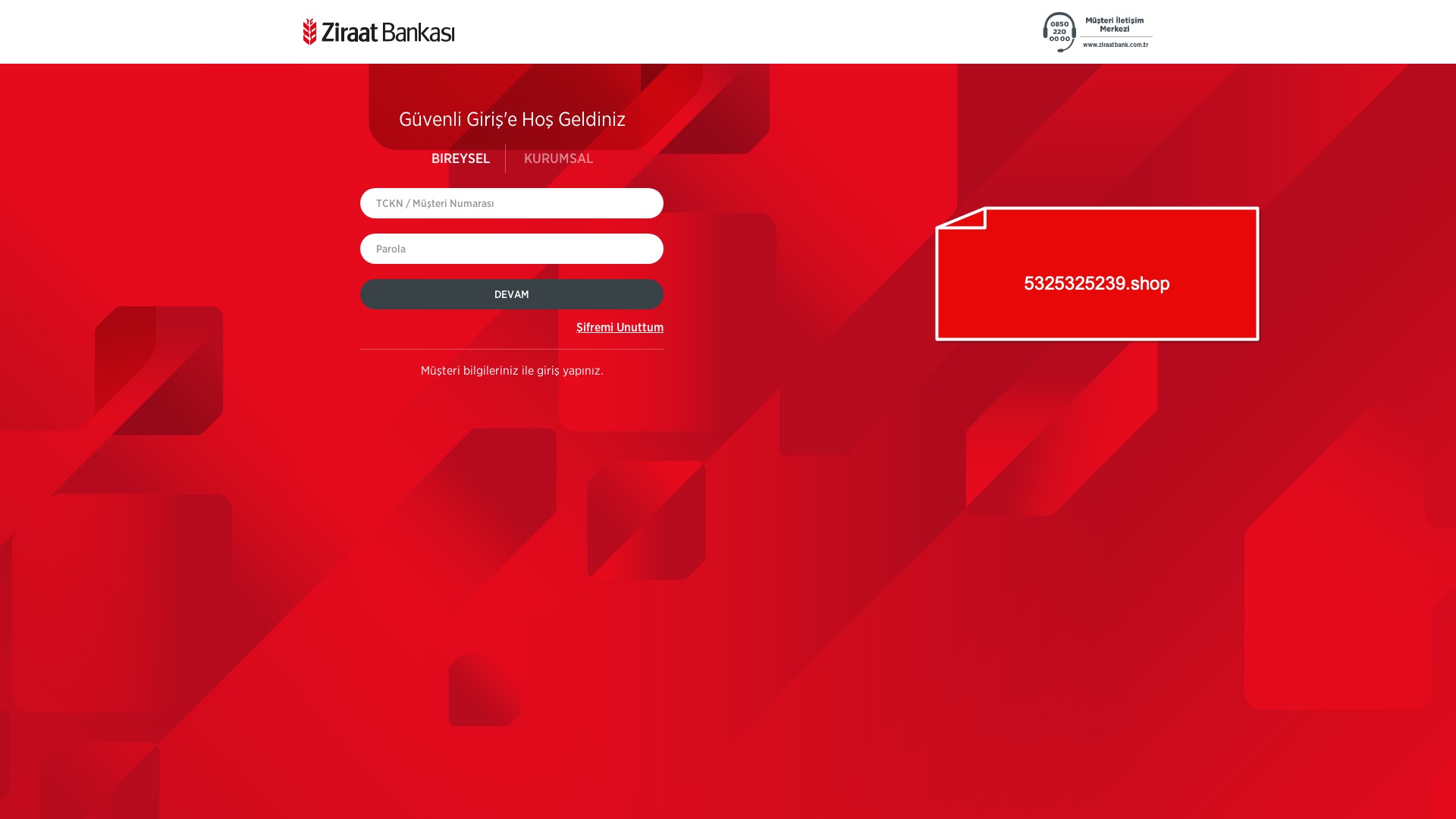

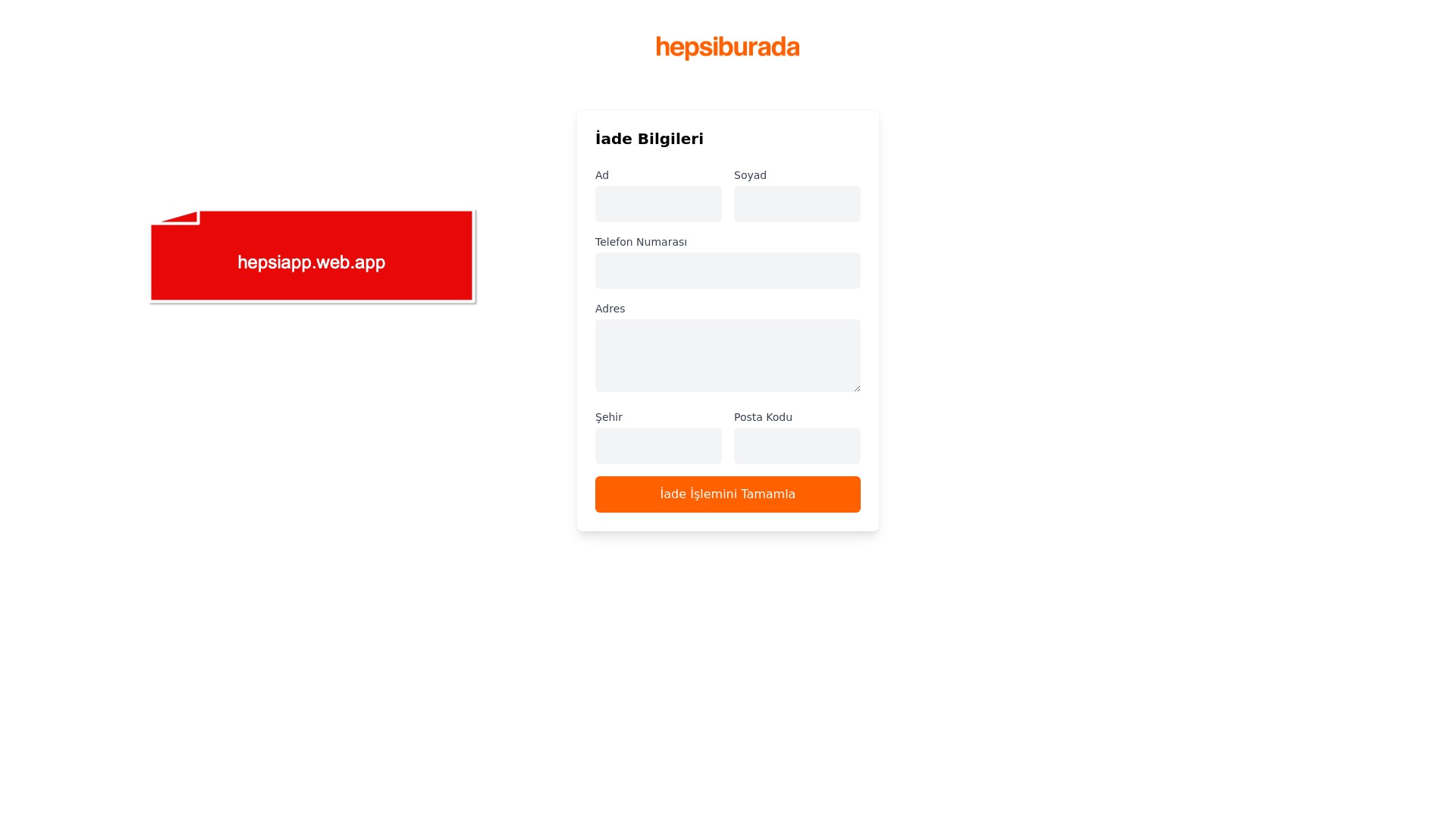

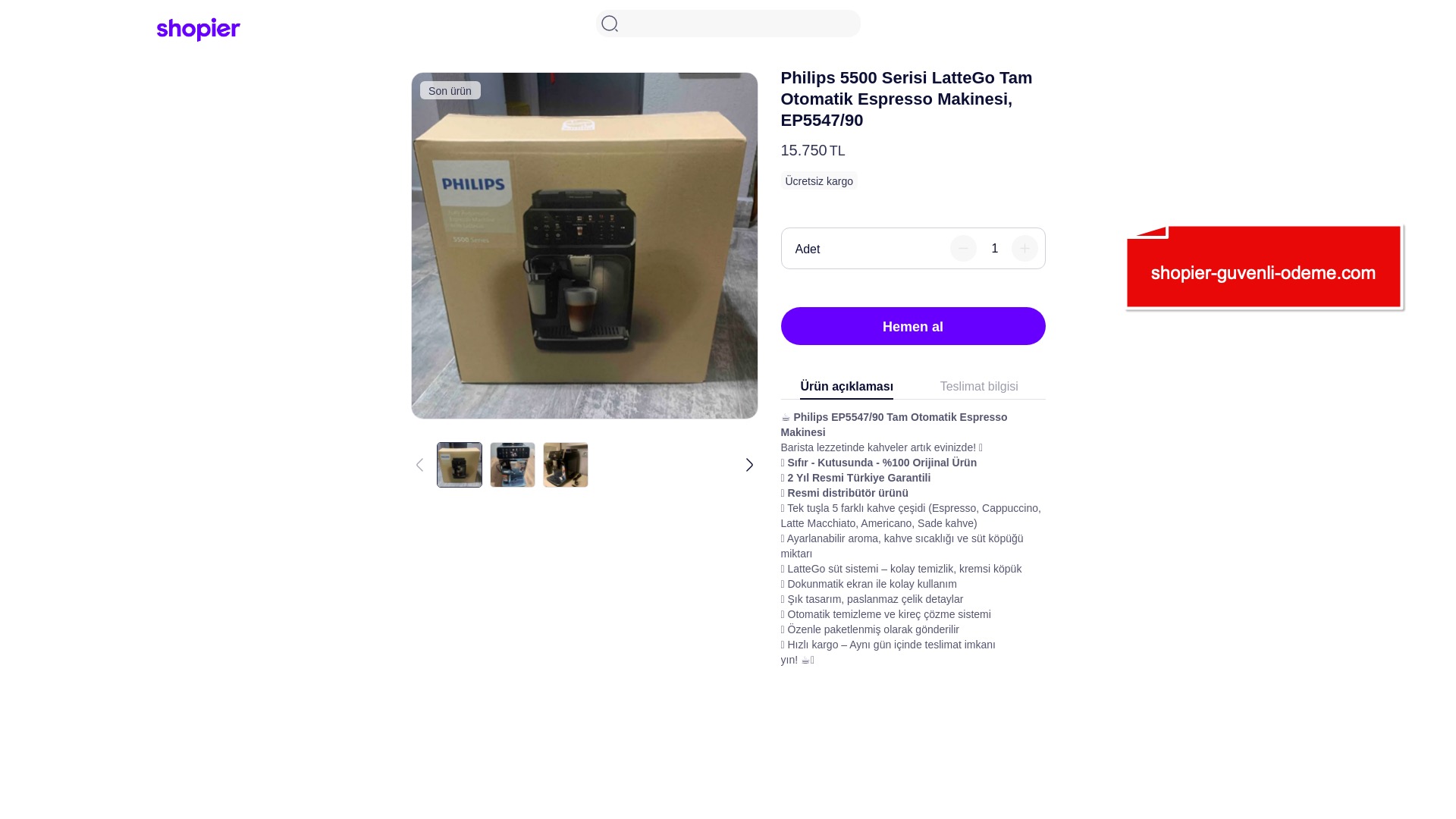

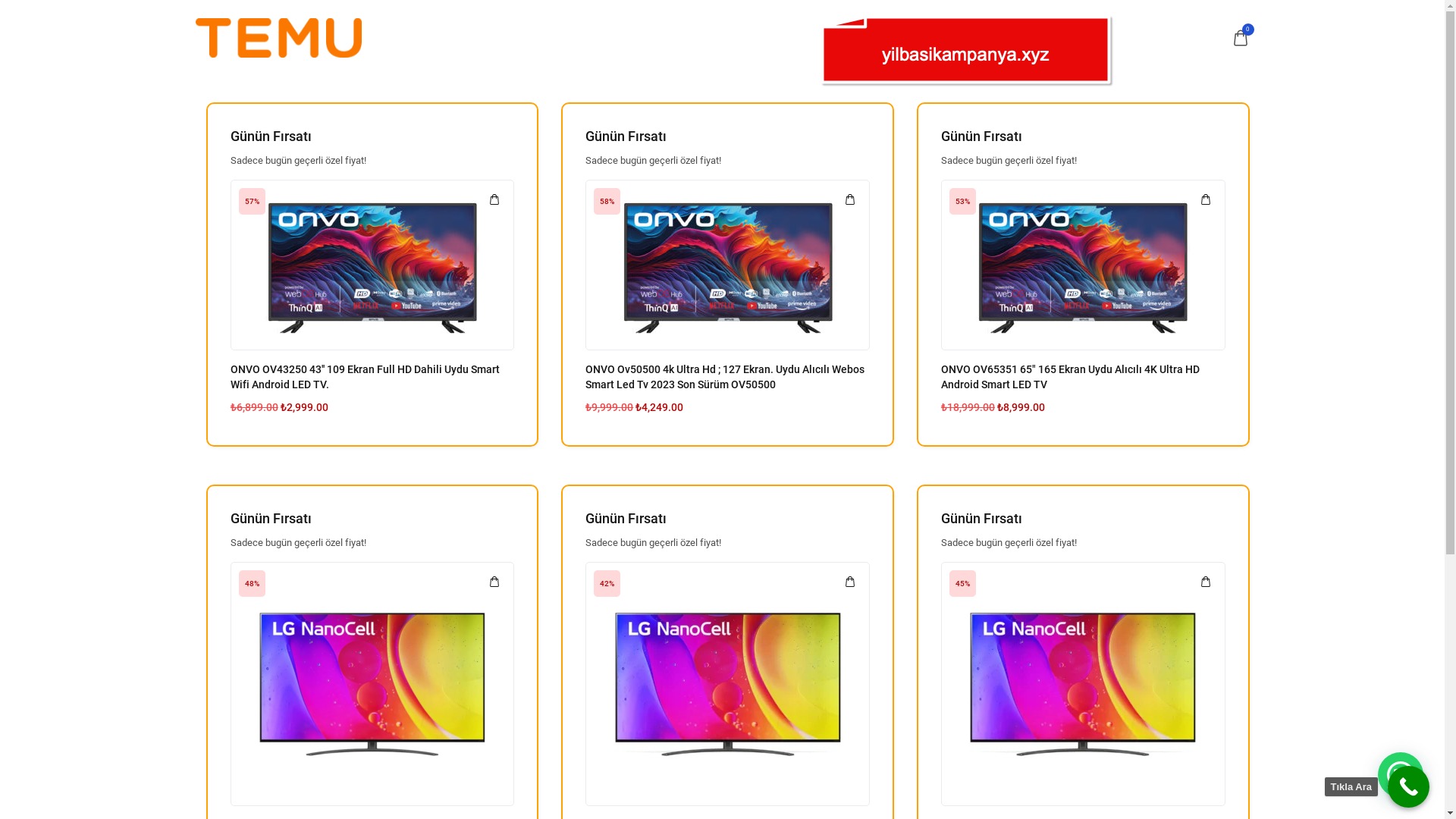

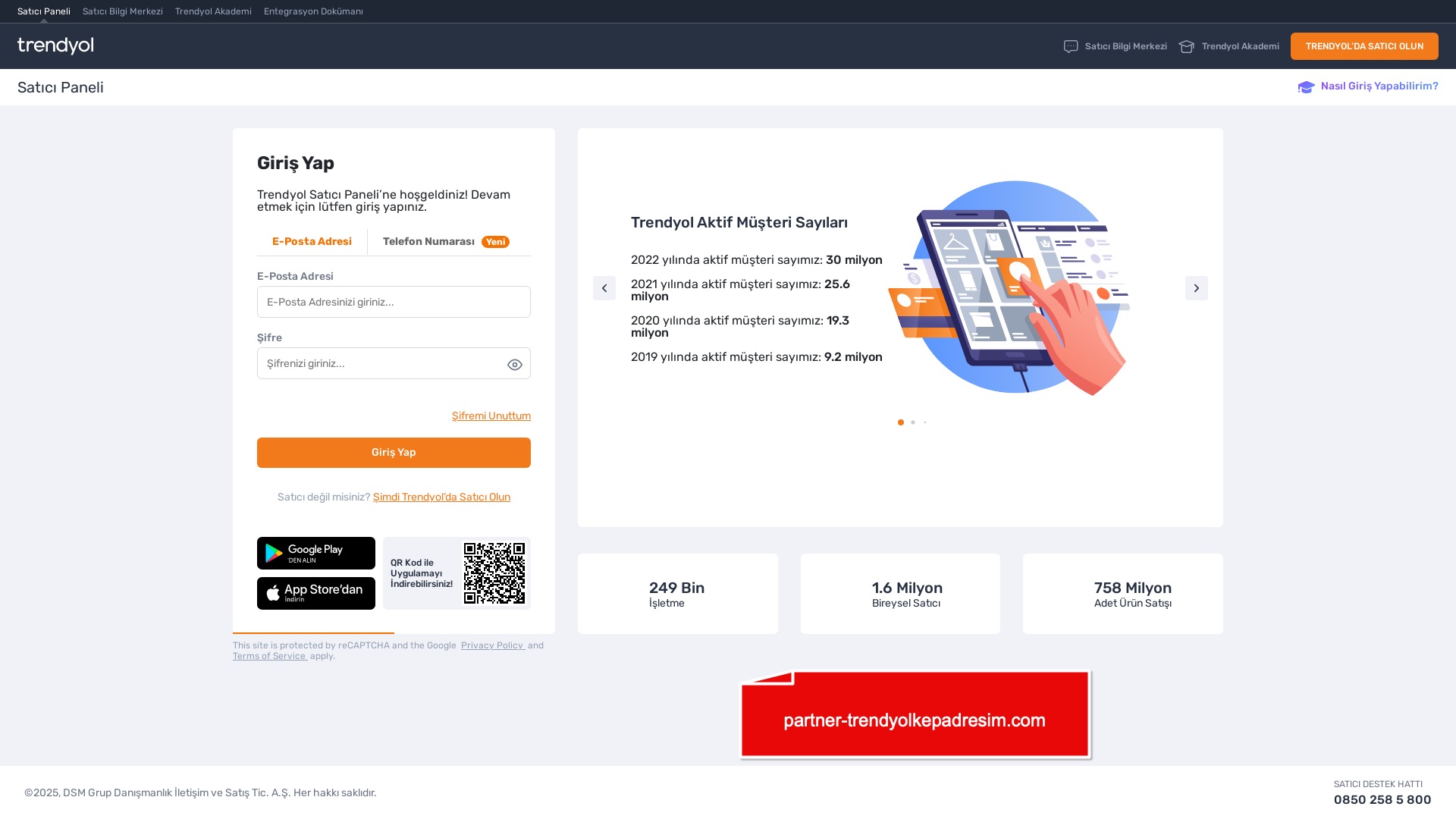

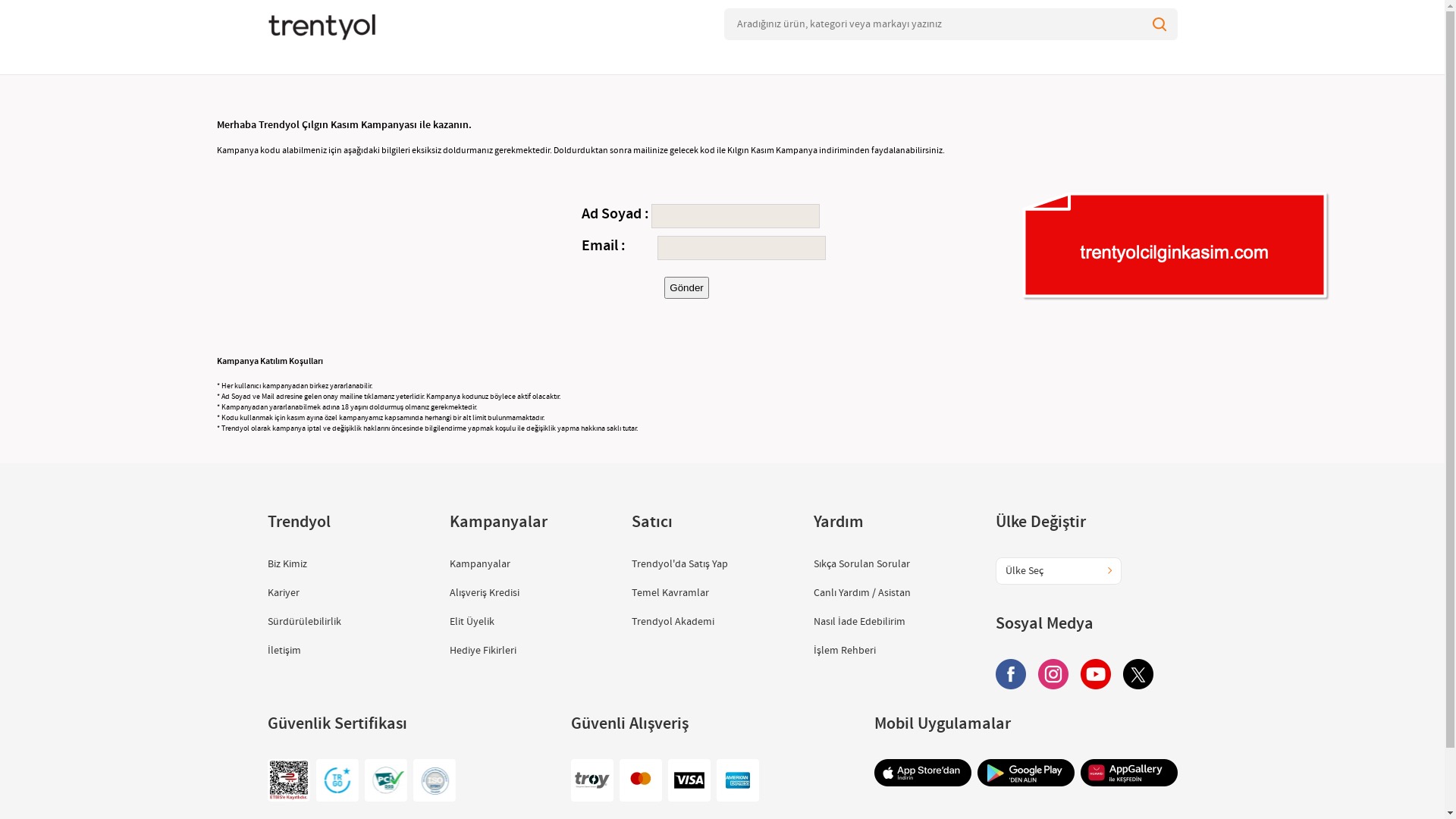

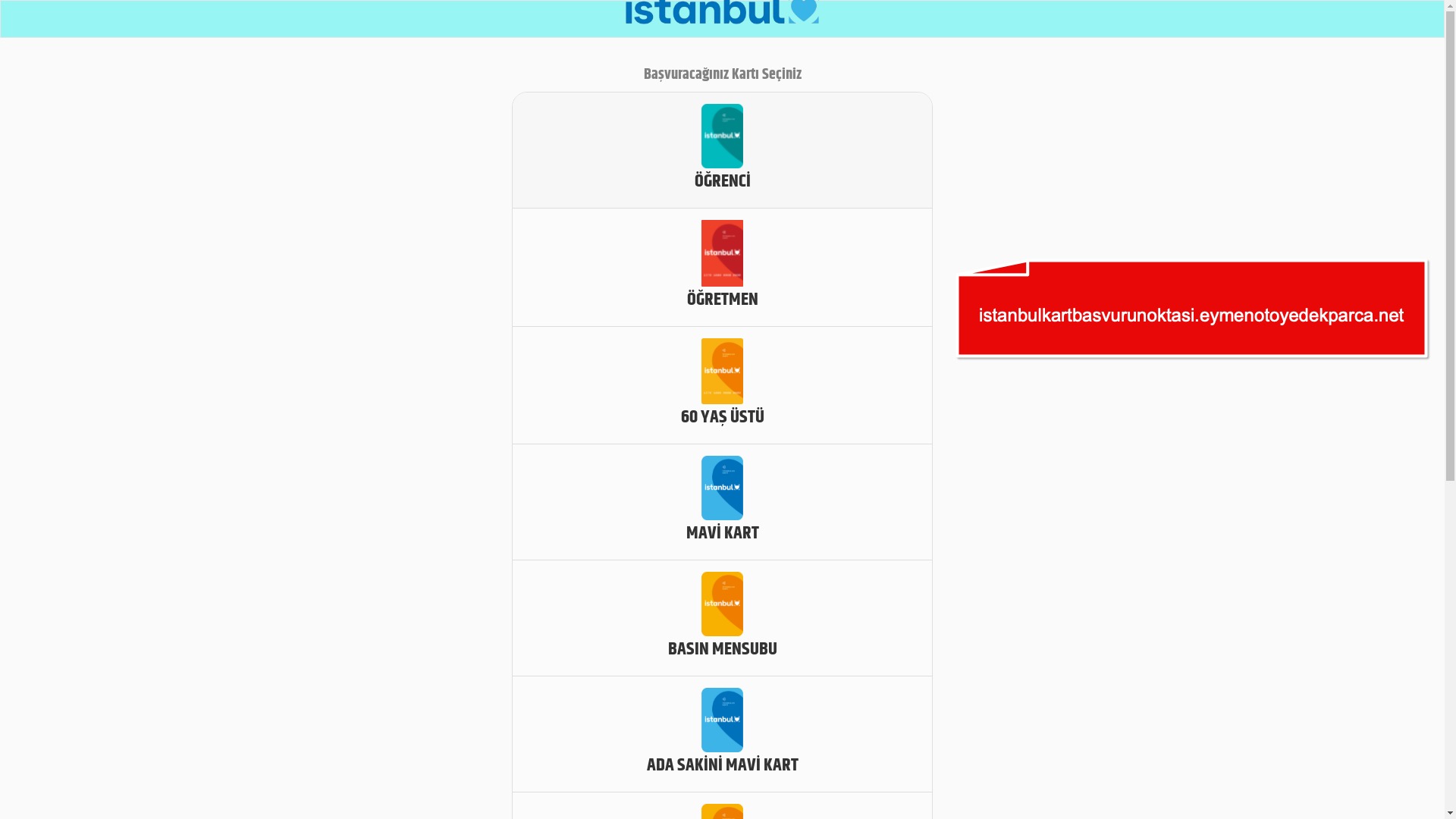

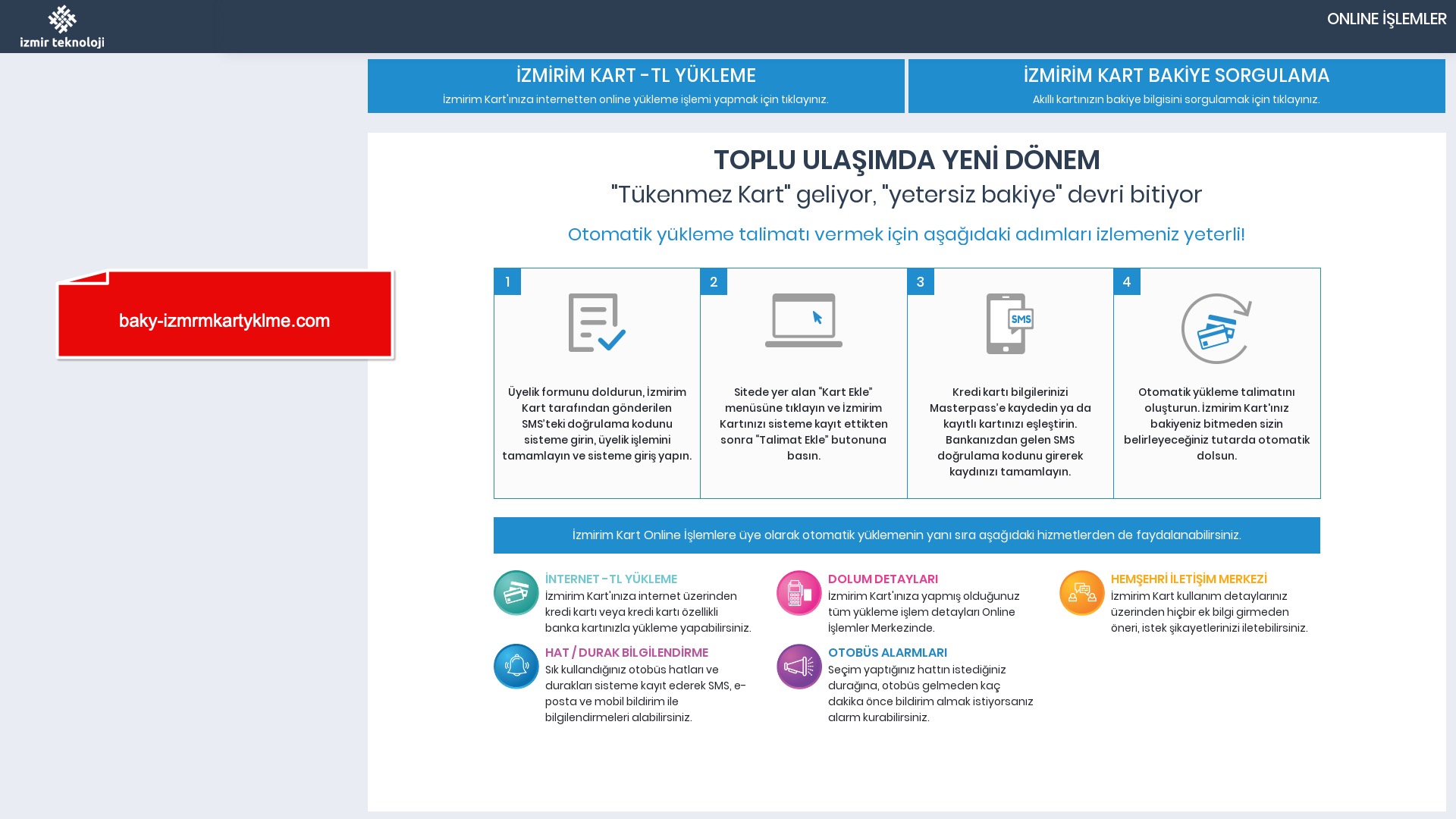

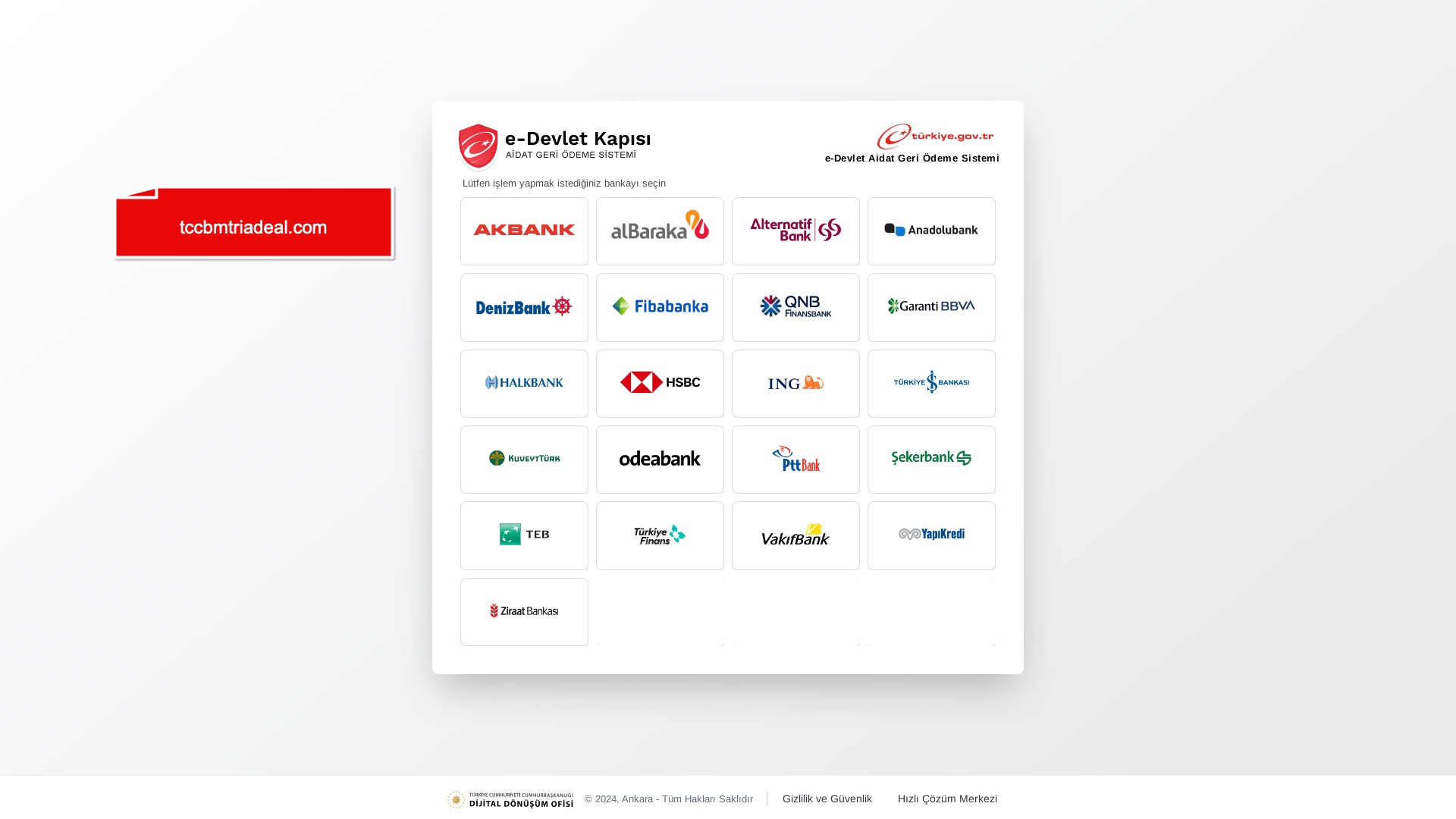

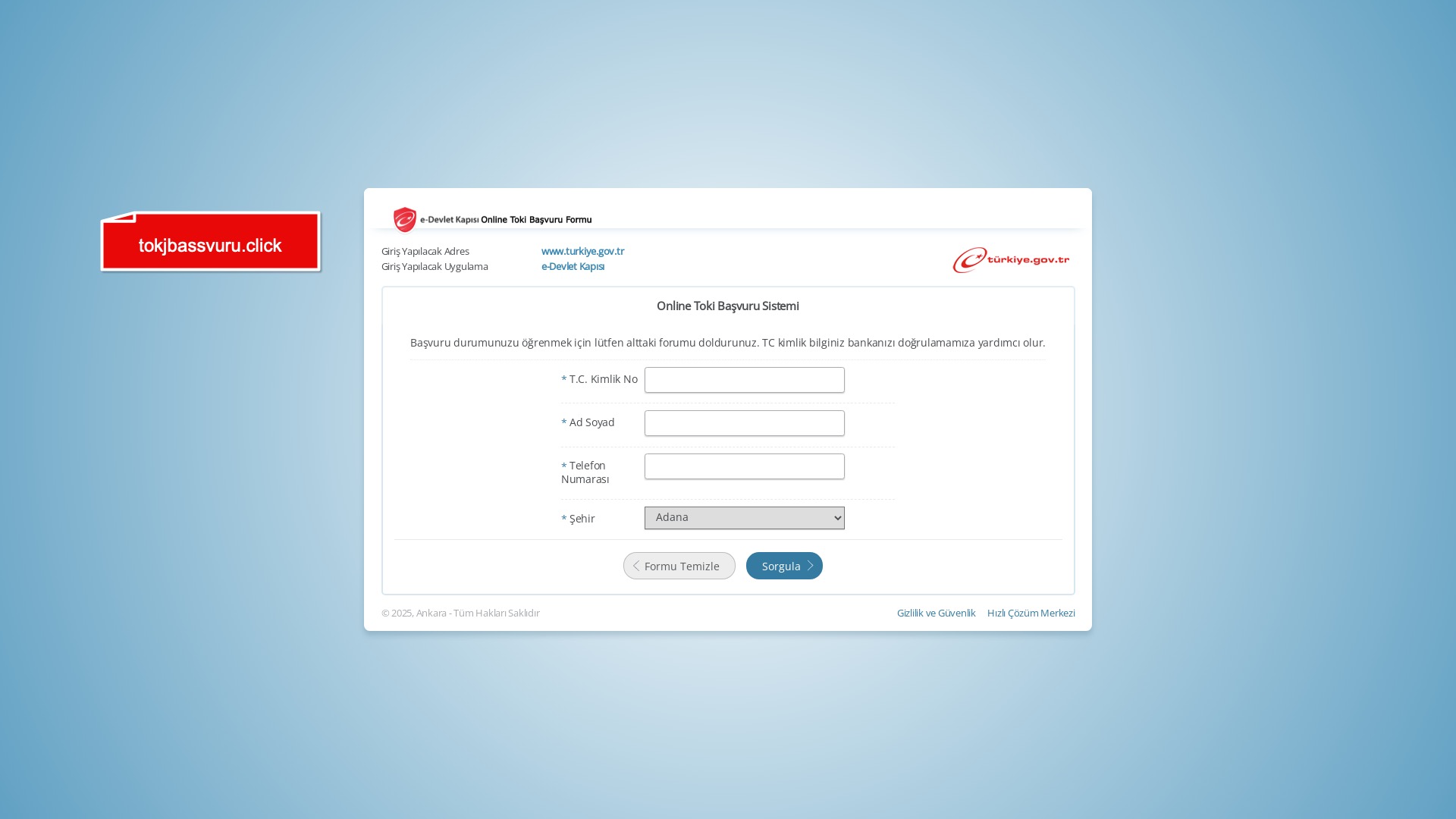

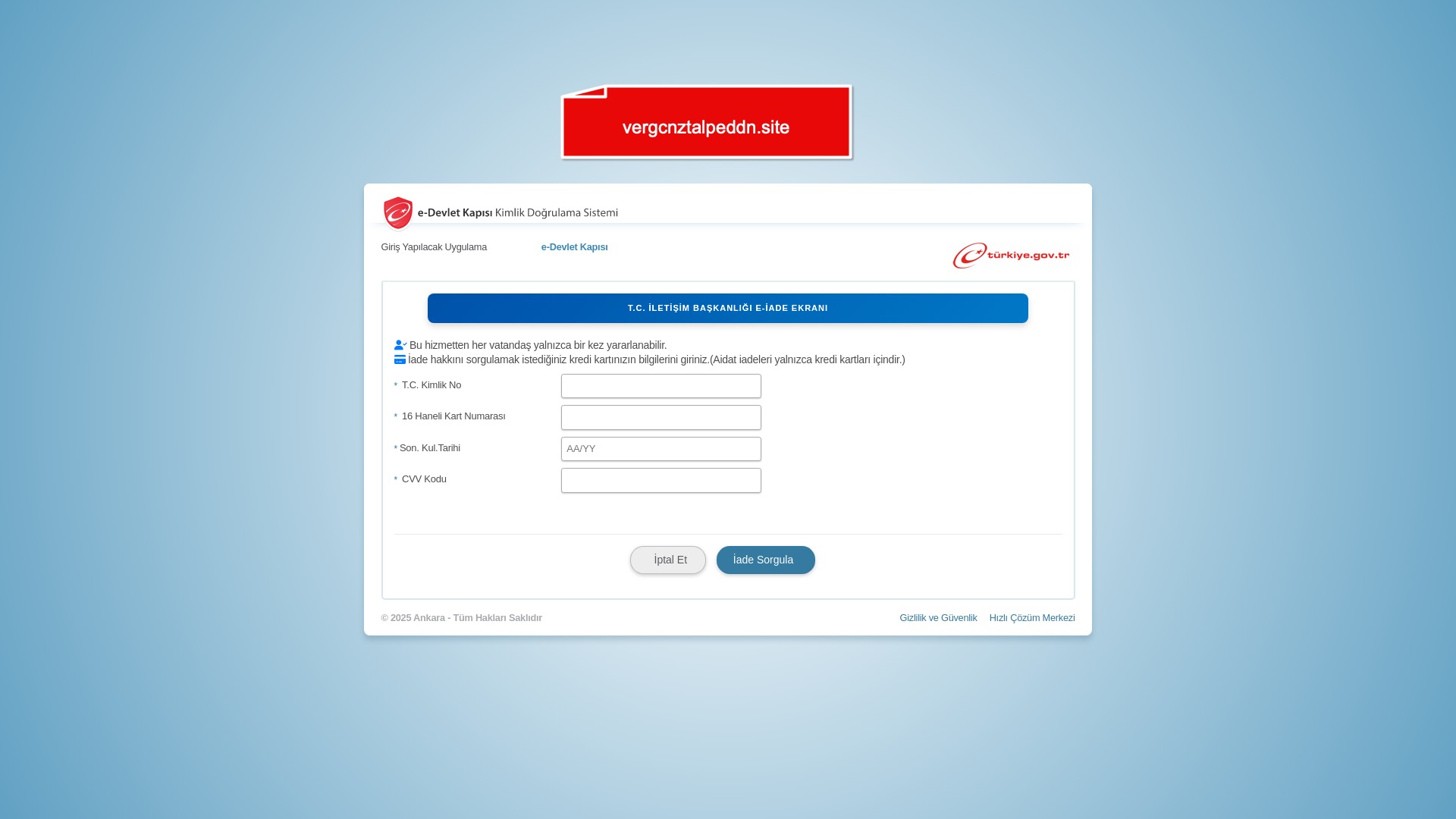

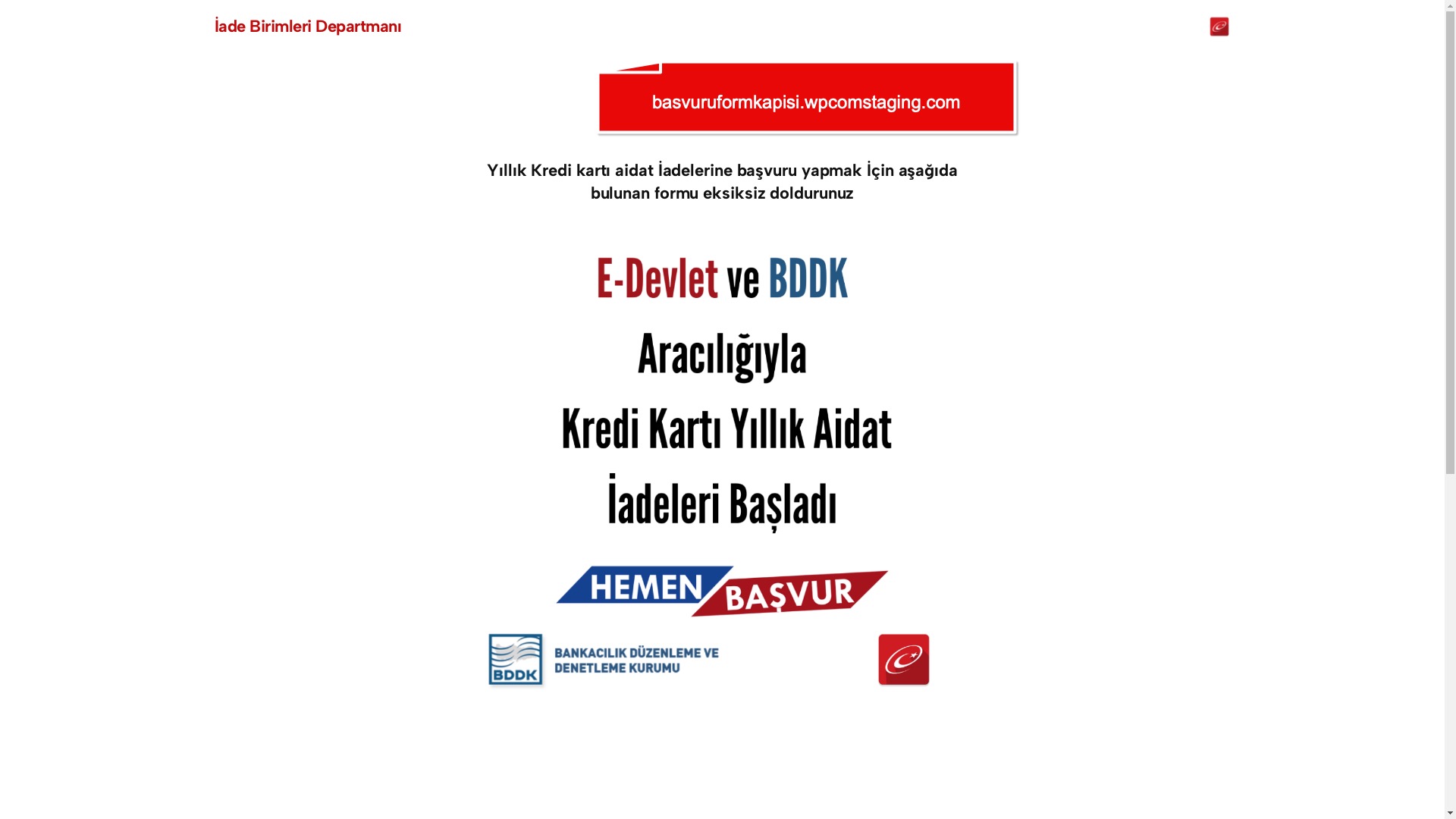

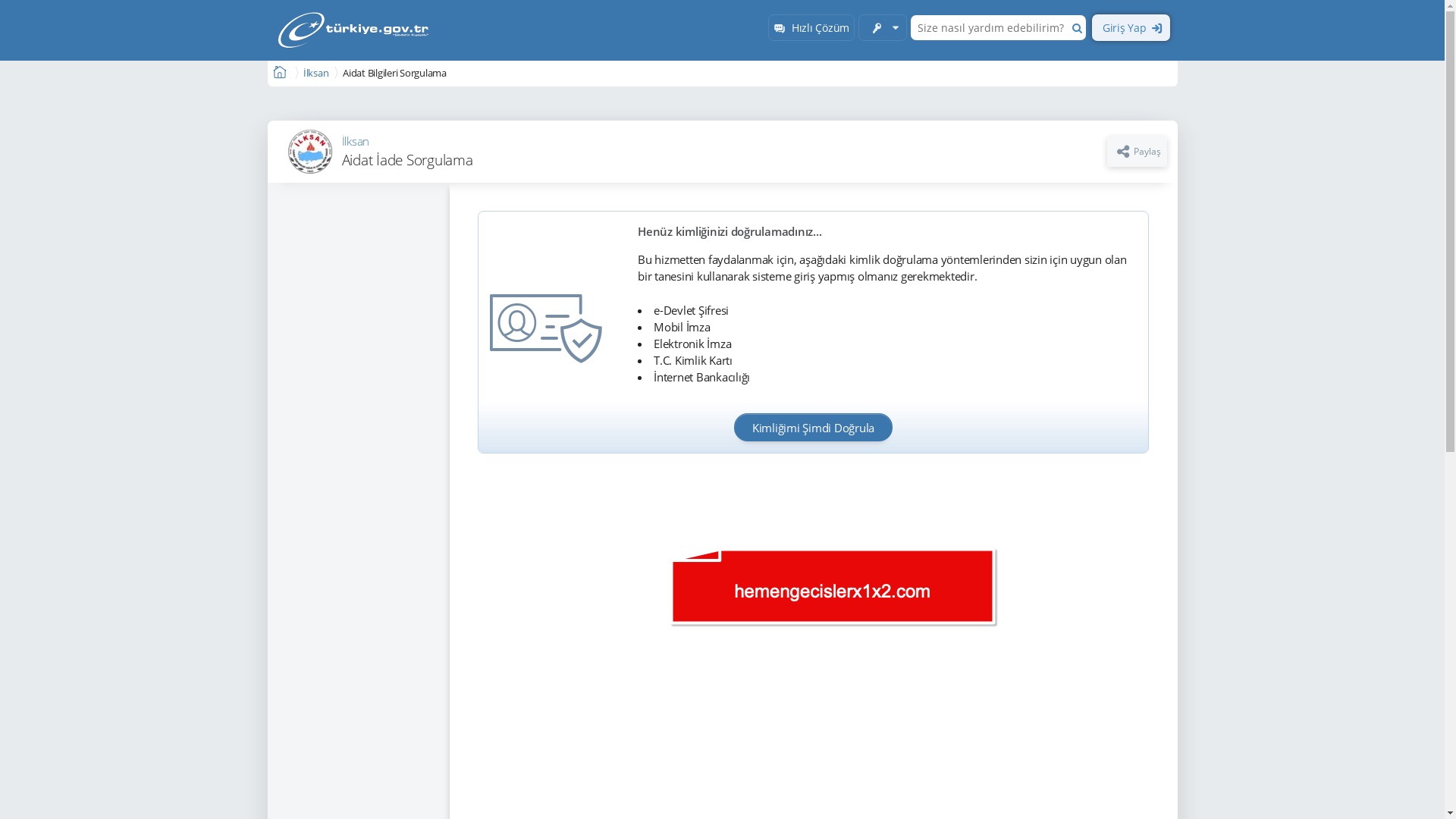

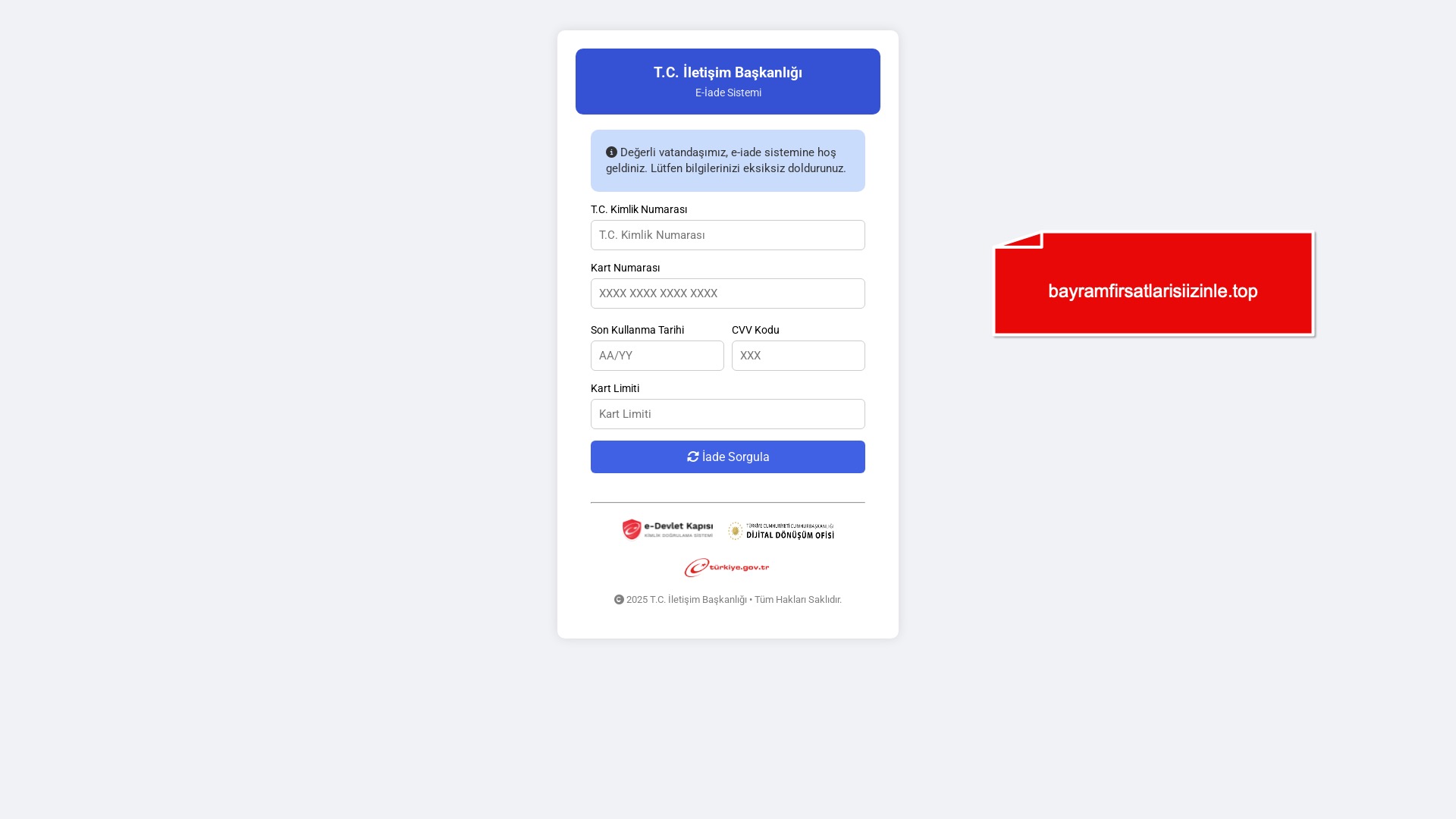

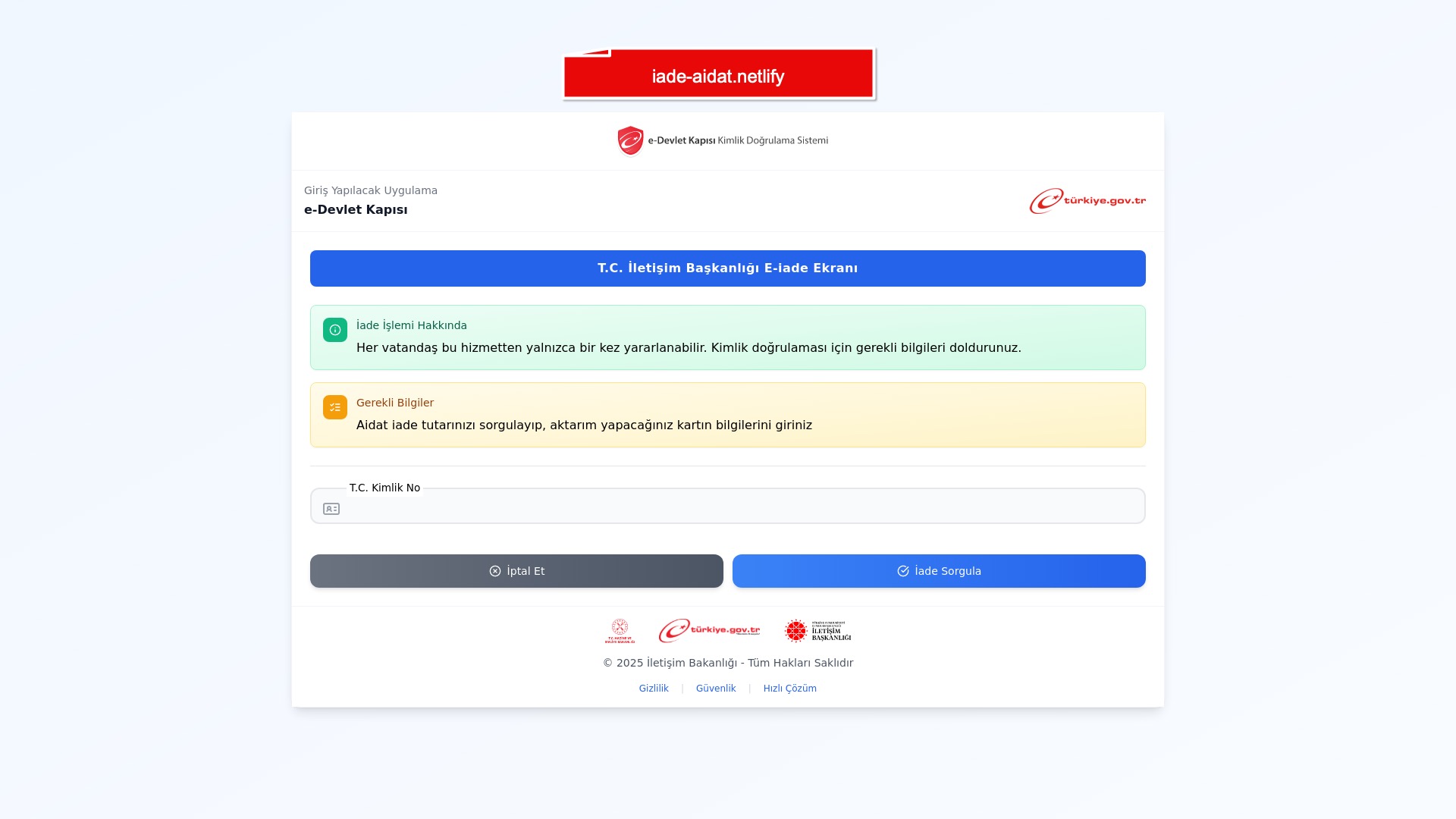

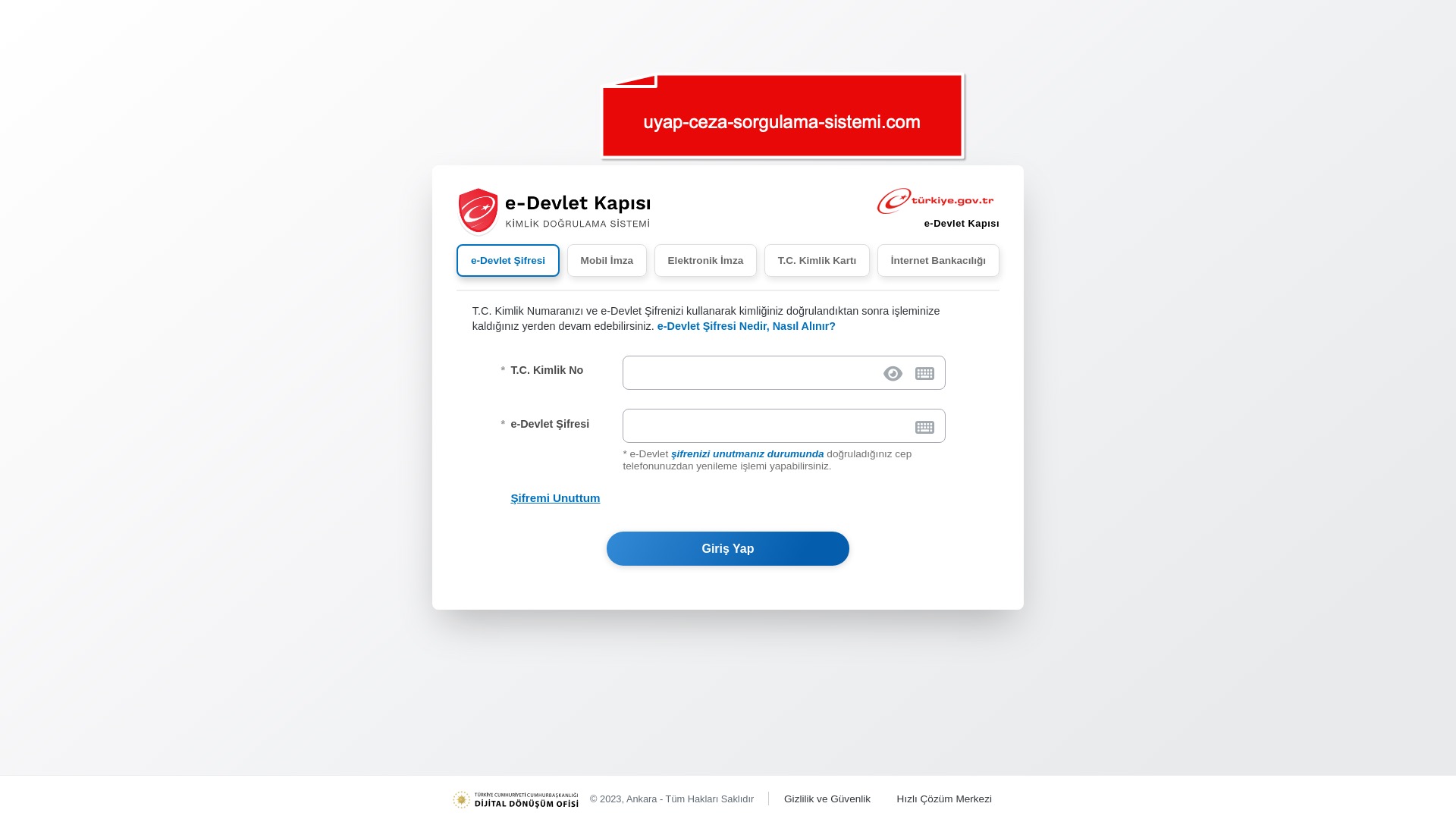

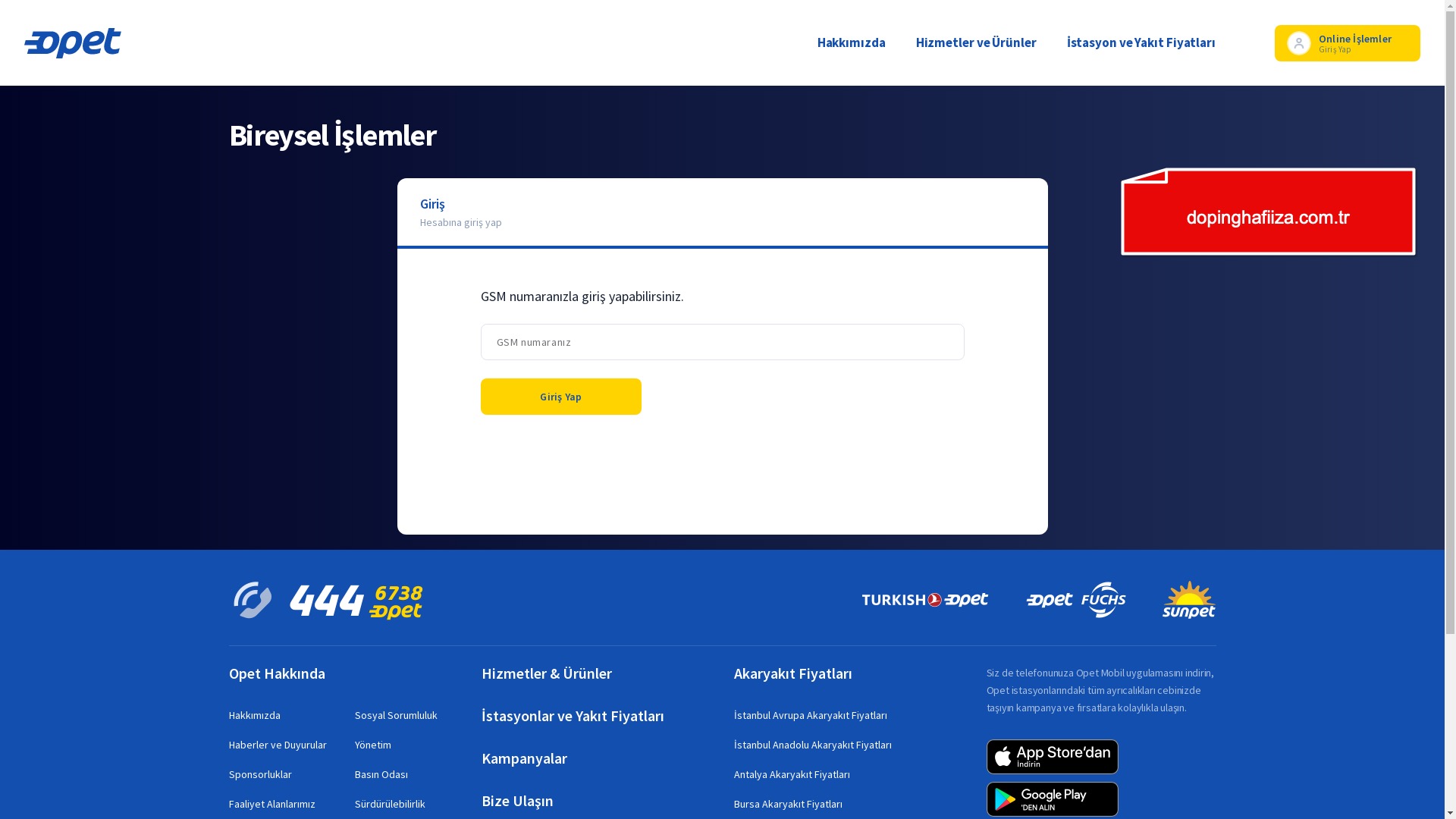

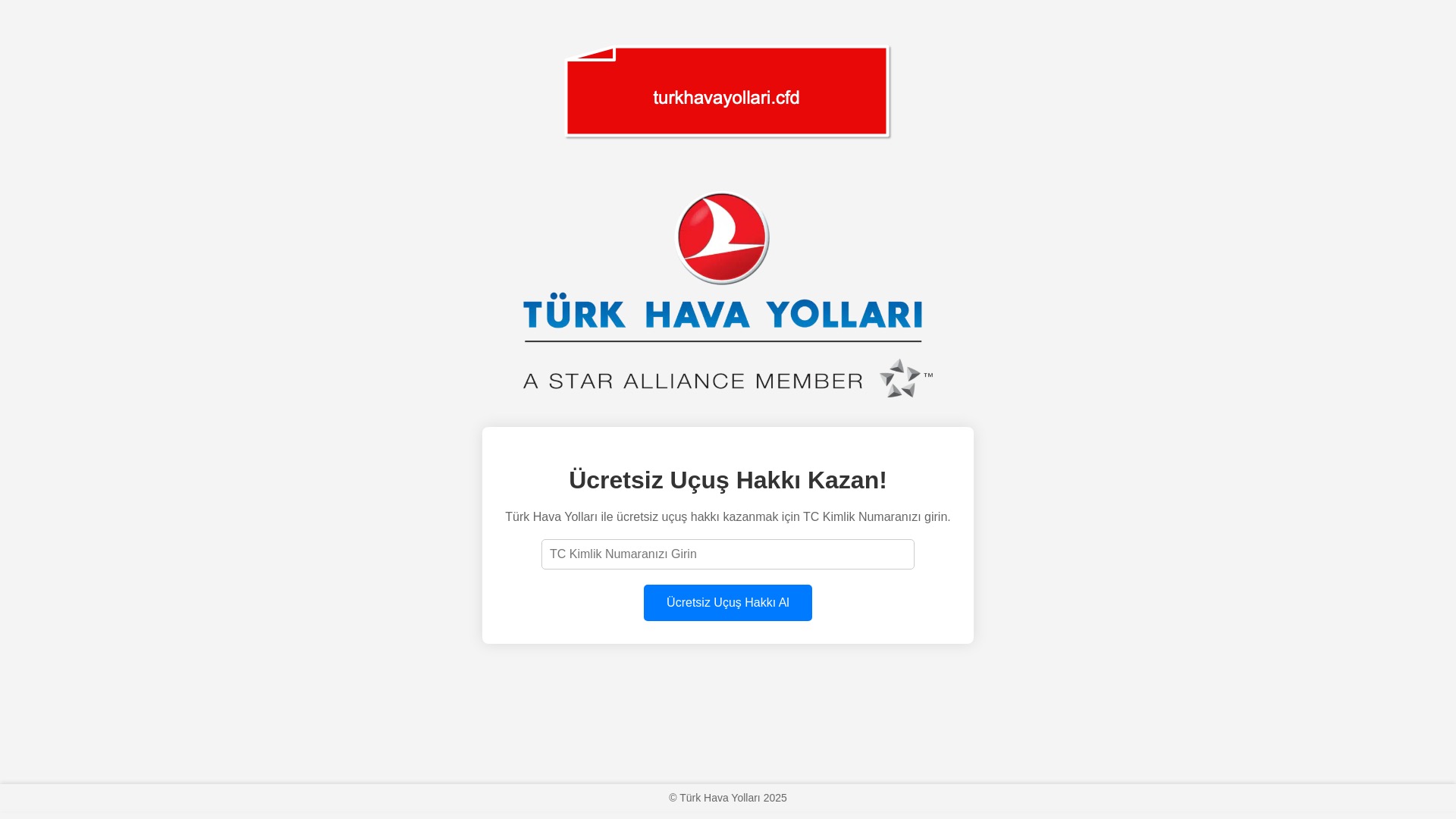

In this section, I wanted to highlight screenshots of phishing sites that impersonate various sectors and well-known brands. The aim is to raise awareness and reduce the number of people falling into these traps.

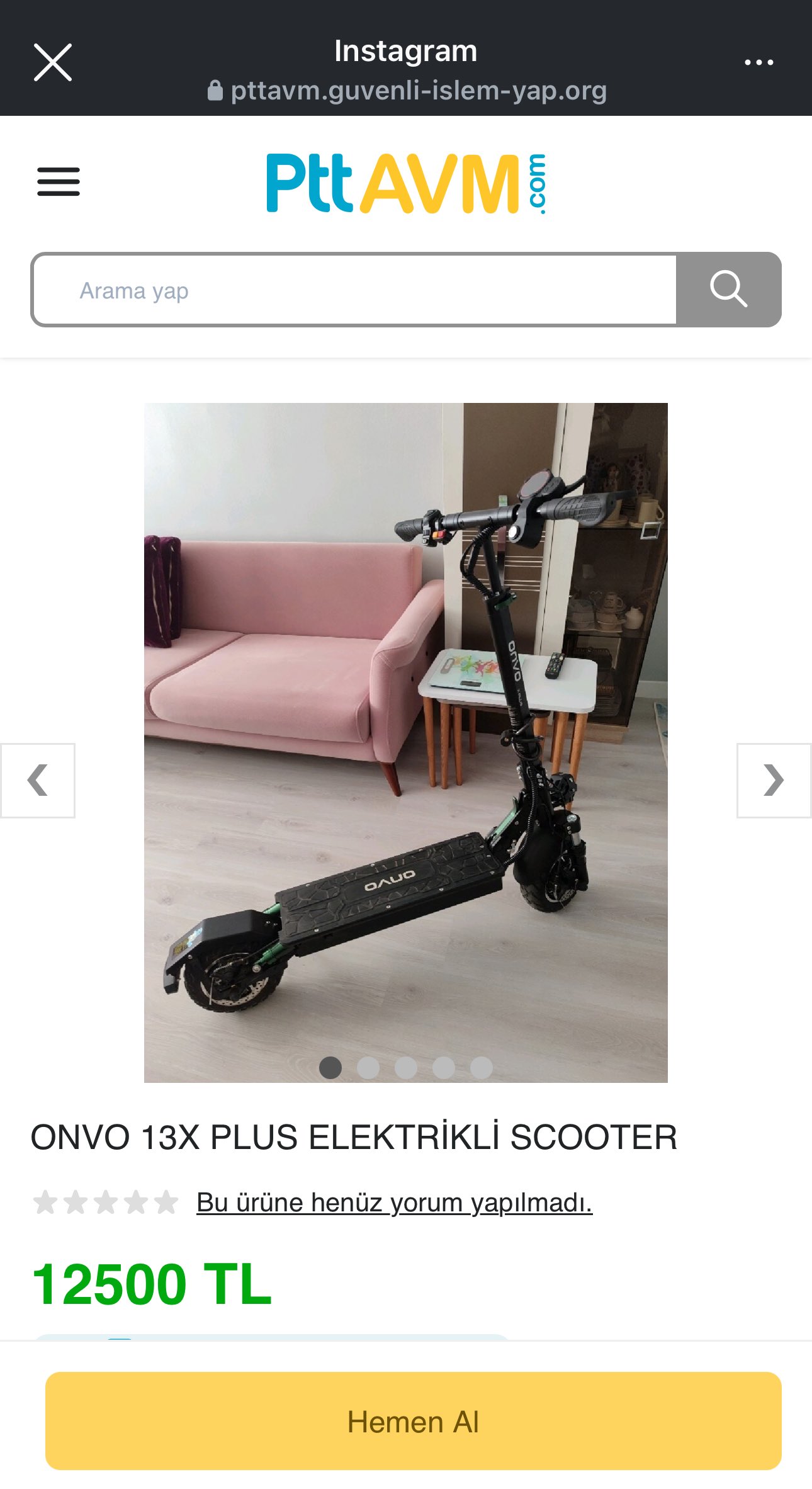

I started by checking whether the claim made by a brazen scammer at the beginning of this post—boasting about scamming 60 people a day by impersonating the PttAVM.com e-commerce platform—was actually true. Were that many people really visiting and getting duped by these phishing sites?

To answer that, I examined screenshots of phishing pages targeting the PttAVM brand. In some of them, I noticed something interesting—online visitor counters displayed at the top corners of the pages.

According to the screenshots, one phishing site had 148 online visitors, while another showed 99. So yes, the scammer’s claim may not have been an exaggeration after all.

As I continued examining the images, I stumbled upon yet another phishing site—this time impersonating the restaurant chain Köfteci YUSUF. Once again, it became painfully clear that scammers know no bounds—no language, faith, or identity. When fraud is involved, they’ll wear any mask and stop at nothing.

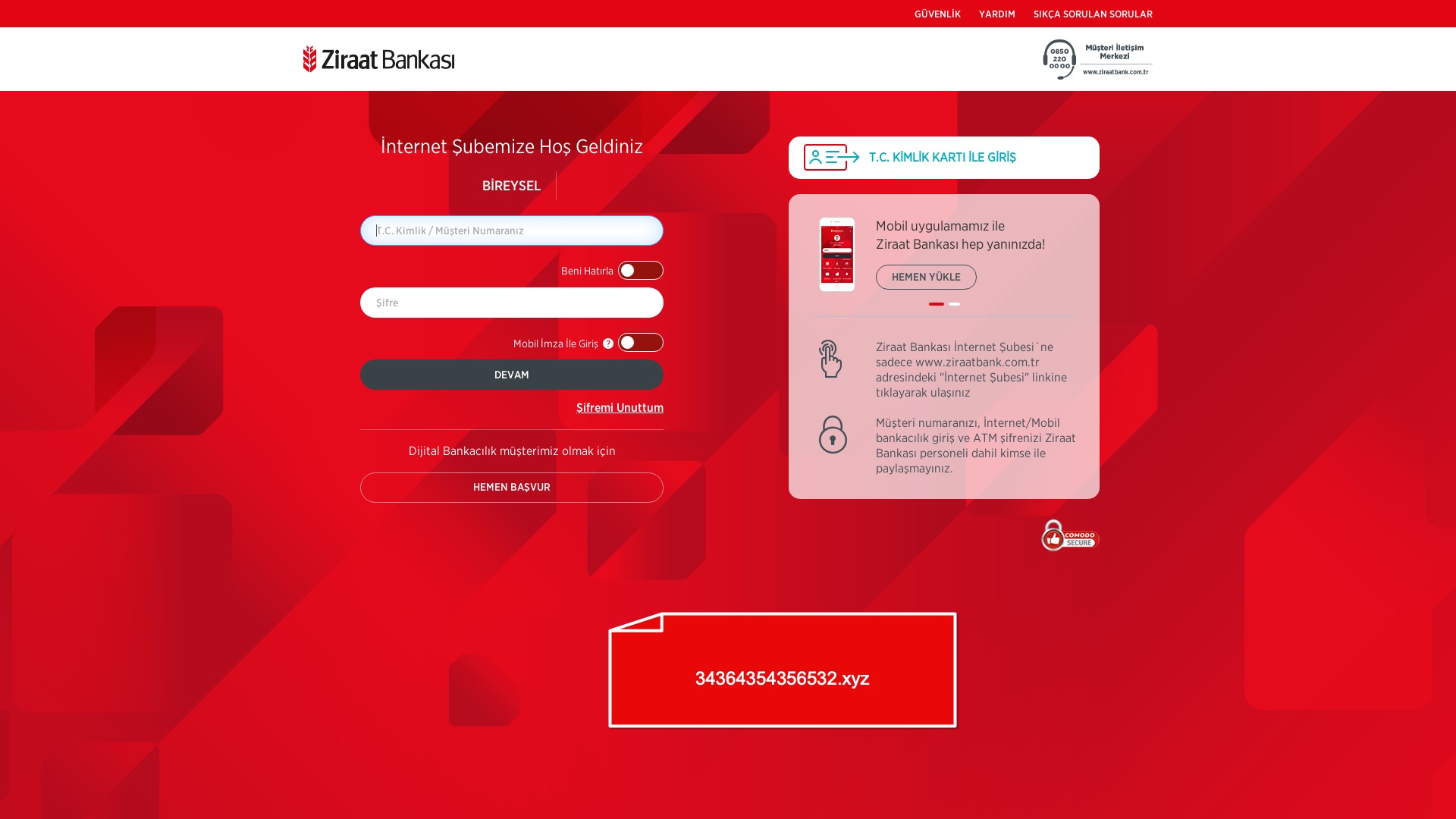

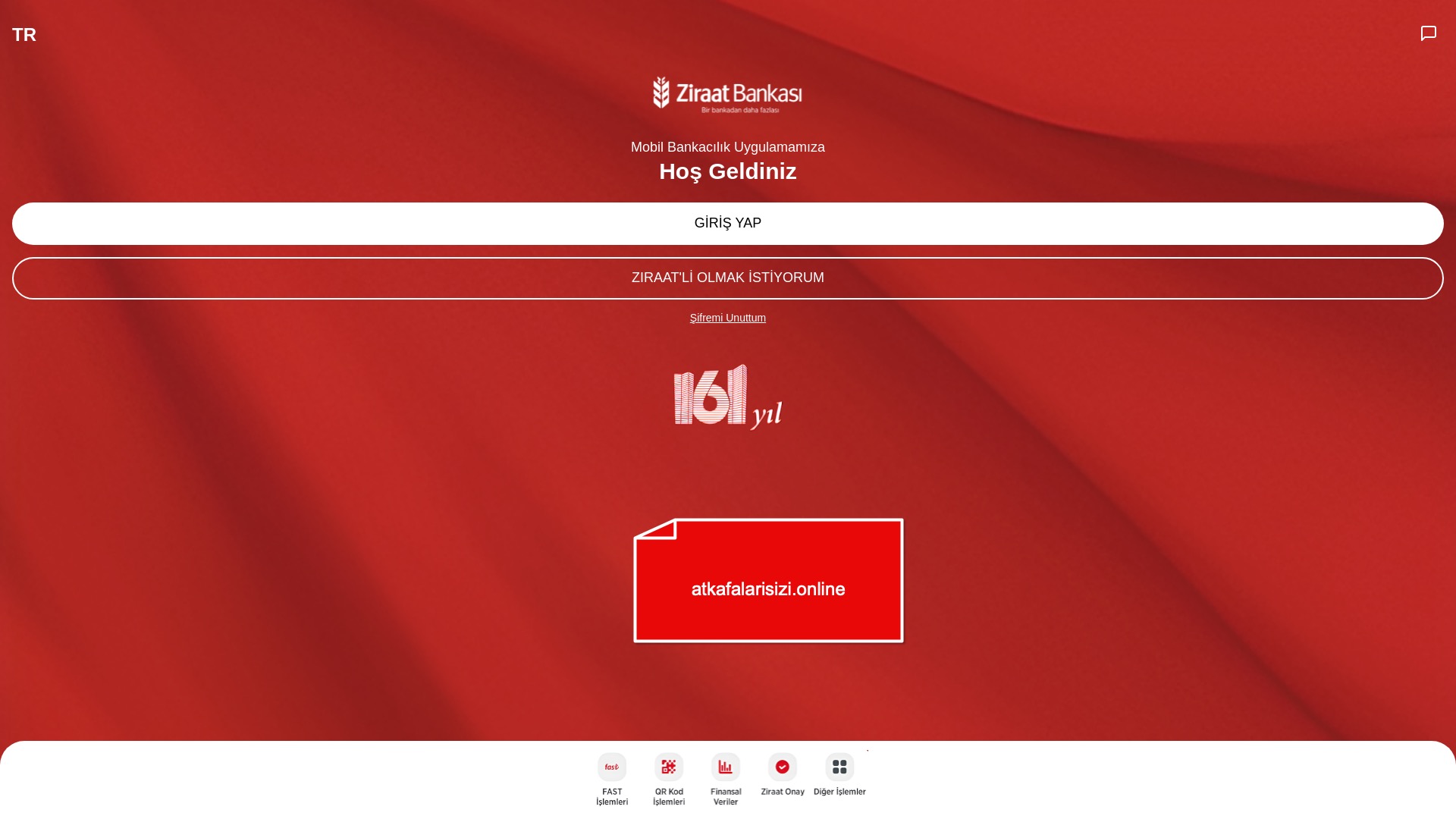

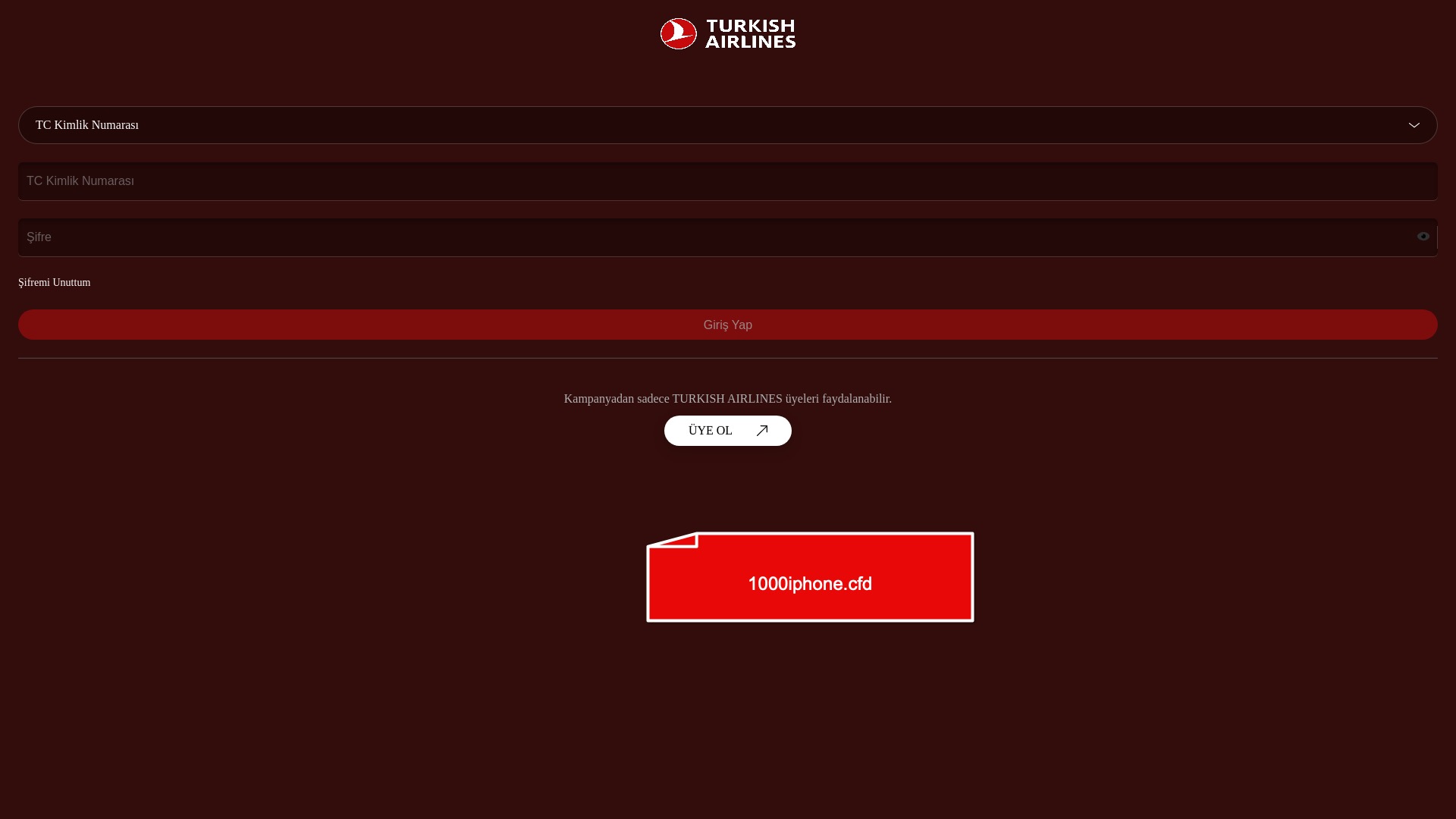

When it comes to banks and financial institutions, it’s obvious that scammers pay special attention to detail, especially in their page designs to boost credibility. In several screenshots, I even saw them emphasize words like Urgent to spark panic and push victims to act without thinking.

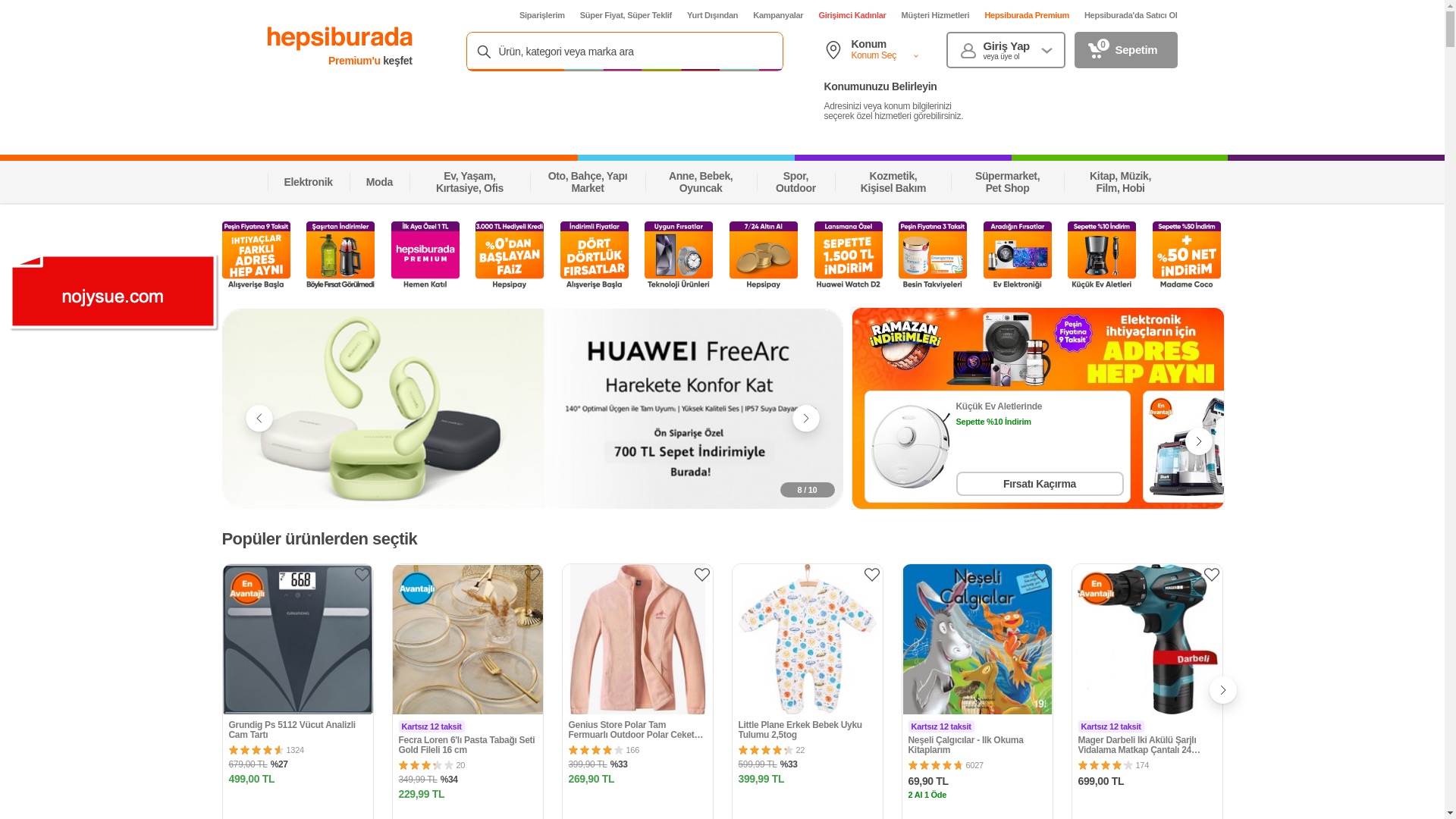

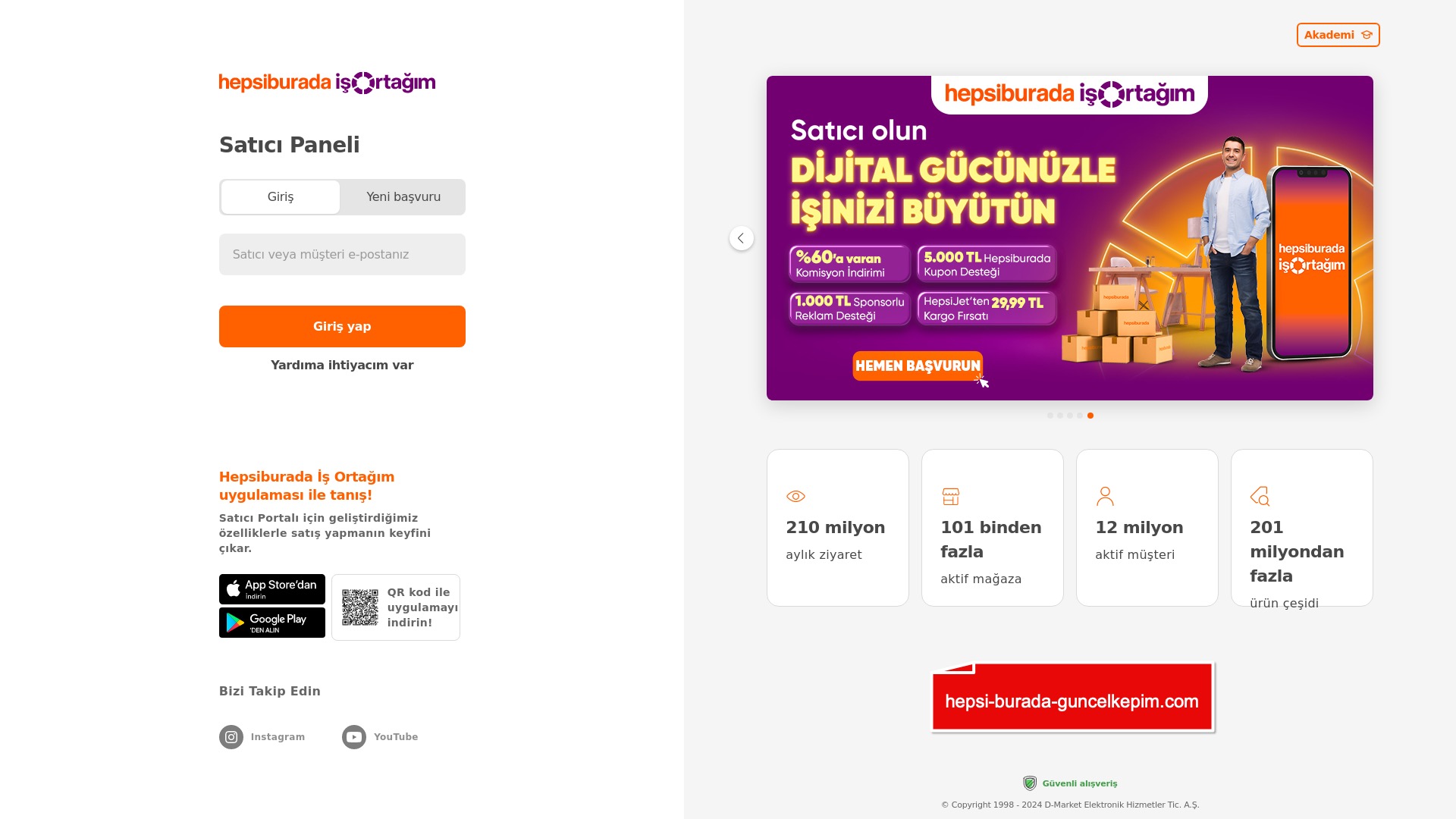

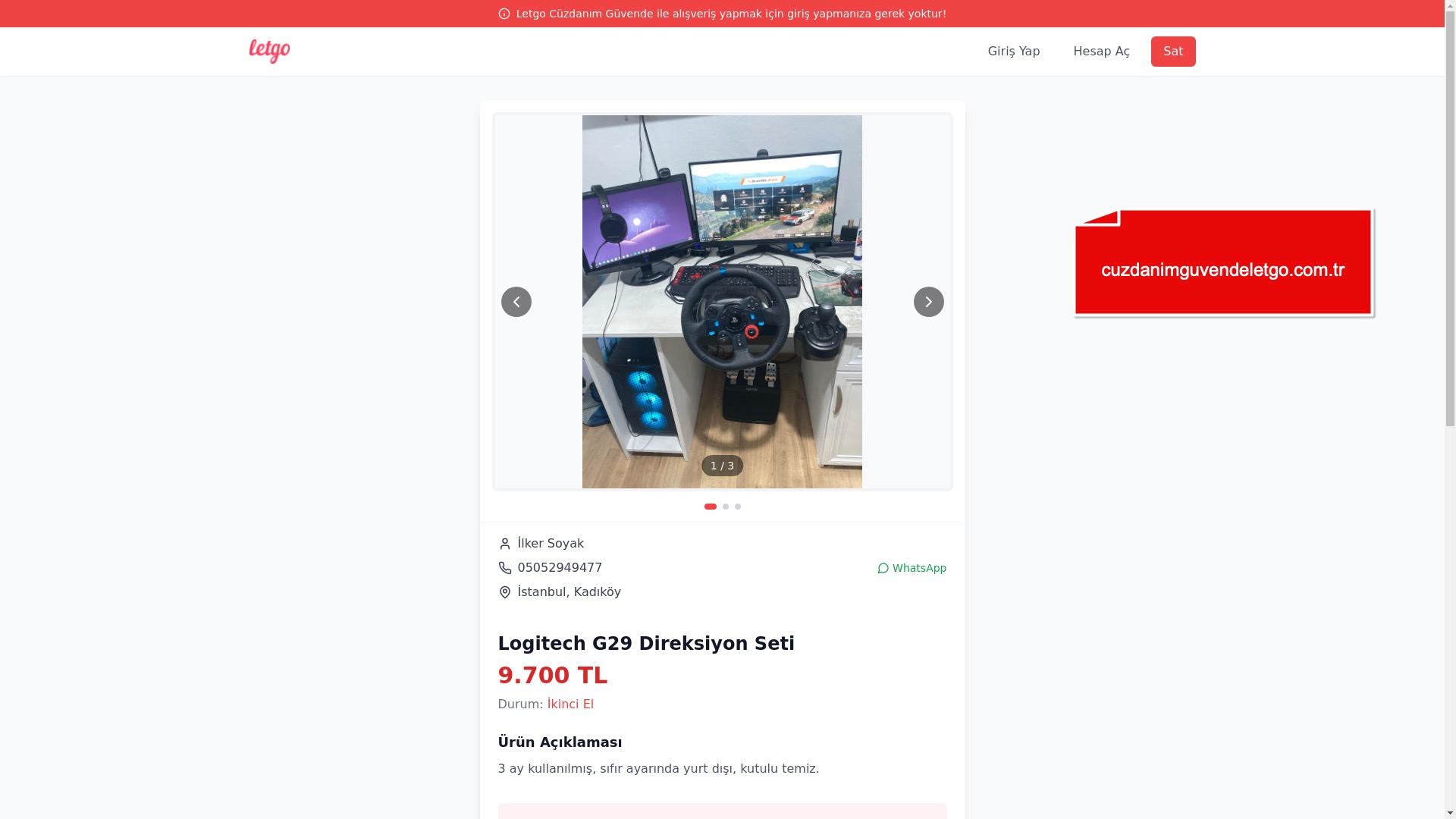

E-commerce brands, especially in the retail sector, were also among the scammers’ top picks for phishing sites—targeting users hoping to score deals on products at unusually low prices.

I had previously come across quite a few phishing sites abusing the name of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, but seeing the Izmir Metropolitan Municipality targeted was new to me — it seems scammers have now added it to their radar as well.

What stood out was that fake e-Government (e-Devlet) sites targeting Turkish citizens featured a wider range of scenarios compared to phishing sites in other categories.

Although fewer in number, it was clear that the remaining sectors and corporate brands were also being targeted by scammers.

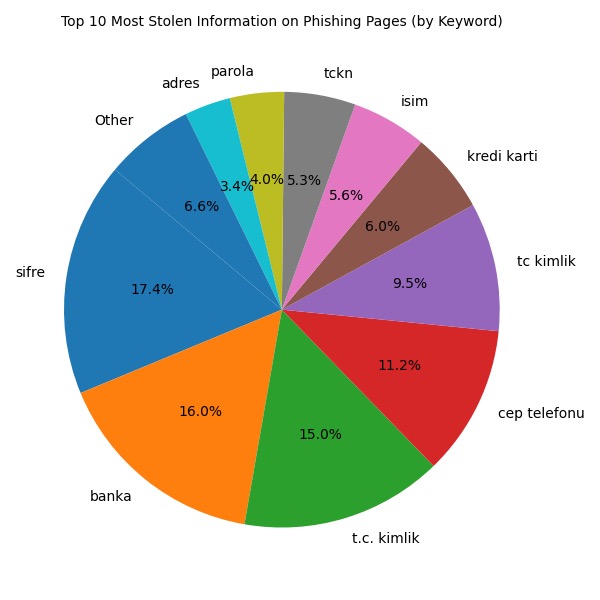

Which of Our Information Are They After?

After satisfying part of my curiosity, I turned my attention to discovering which types of personal information were primarily being stolen on the homepages of these phishing websites. To do this, I once again summoned my loyal assistant, ChatGPT, to write another Python script (phishing_analysis.py), which, using OCR, detected the presence of the following keywords:

KEYWORDS = {

“Credentials”: [“şifre”, “password”, “parola”, “giriş”, “login”, “username”, “kullanıcı adı”, “user name”, “sifre”],

“Identity”: [“t.c. kimlik”, “tc kimlik”, “t.c kimlik”, “soyad”, “doğum tarihi”, “anne kızlık”, “isim”, “tckn”],

“Bank”: [“kart numarası”, “cvv”, “iban”, “hesap”, “banka”, “son kullanma”, “kredi kartı”, “kredi karti”],

“Contact”: [“cep telefonu”, “e-mail”, “email”, “adres”, “eposta”, “e-posta”],

}

As expected, the scammers were primarily after TCKN (Turkish ID Number) (29.8%) and passwords (21.4%), which are often used as login credentials for banking systems.

Domain Name Analysis

As is well known, scammers try to make not only their phishing websites but also their domain names as convincing and realistic as possible to deceive their victims. That’s why they often include the names of the corporate brands they are targeting in the domain names they register. However, since this also makes it easier for them to get caught, they sometimes resort to a method known as typosquatting.

Typosquatting is the practice of creating fake/phishing websites that closely resemble corporate brand domains but contain small typographical errors.

Some common typosquatting techniques include:

Character Omission: garanti.com.tr → garnti.com.tr

Character Addition: gratis.com → grattis.com

Character Replacement: trendyol.com → trentyol.com

Hyphen/Underscore Insertion: hepsiburada.com → hepsi-burada.com

Homograph Attacks: using Cyrillic “а” instead of Latin “a”

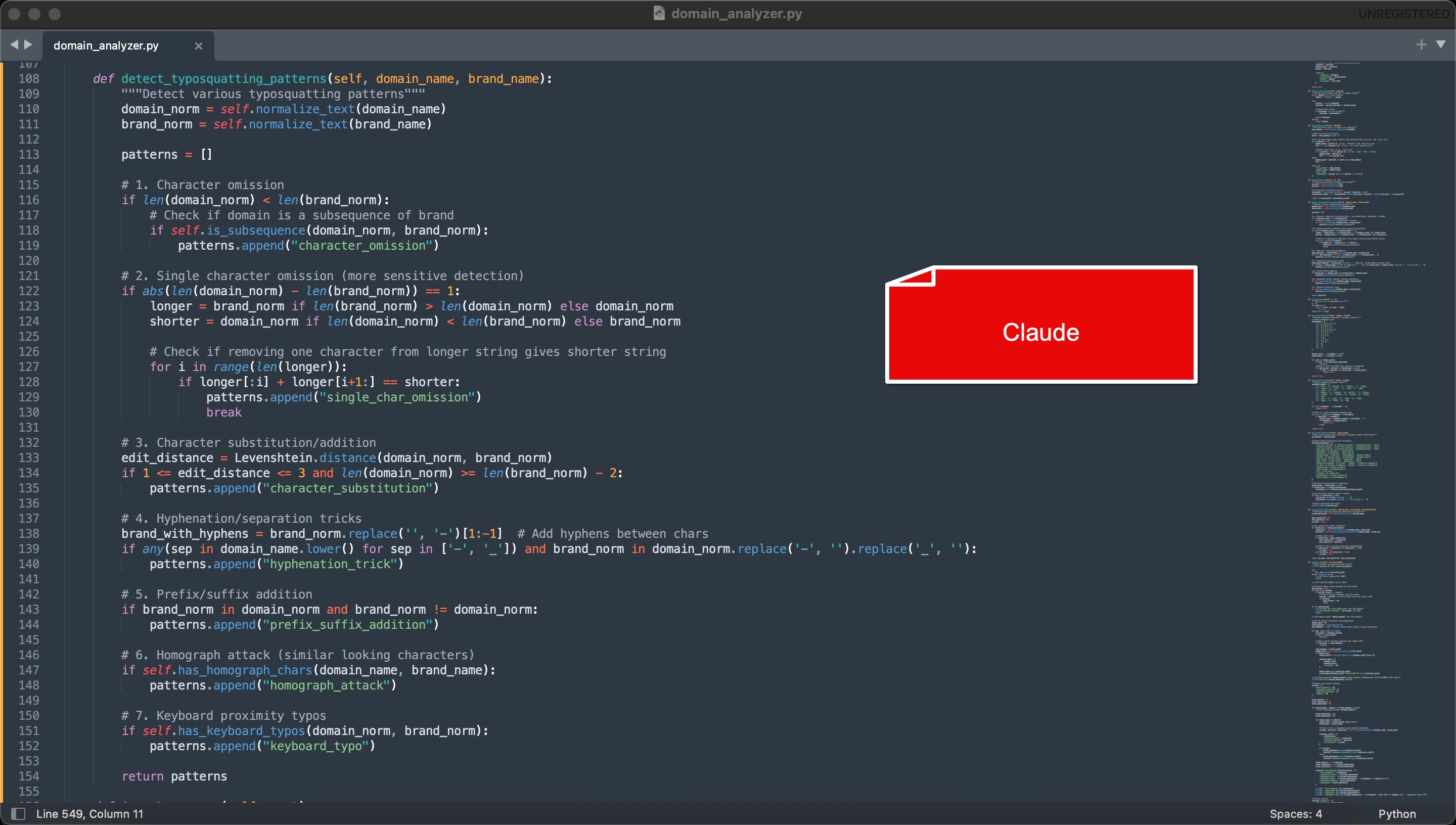

To identify the extensions (.com, .net, .org, .shop, etc.) of domains registered by scammers and measure the rate of typosquatting, I decided to ask ChatGPT to write one final script (phishing_domain.py). However, since it wasn’t able to accurately detect specific examples like those below, I decided to give Claude a shot.

Examples:

vkfbnkkkkmpnyy.duckdns.org

grarntimbasvuuronay-basvur.vercel.app

garantmobil.click

trentyolcilginkasim.com

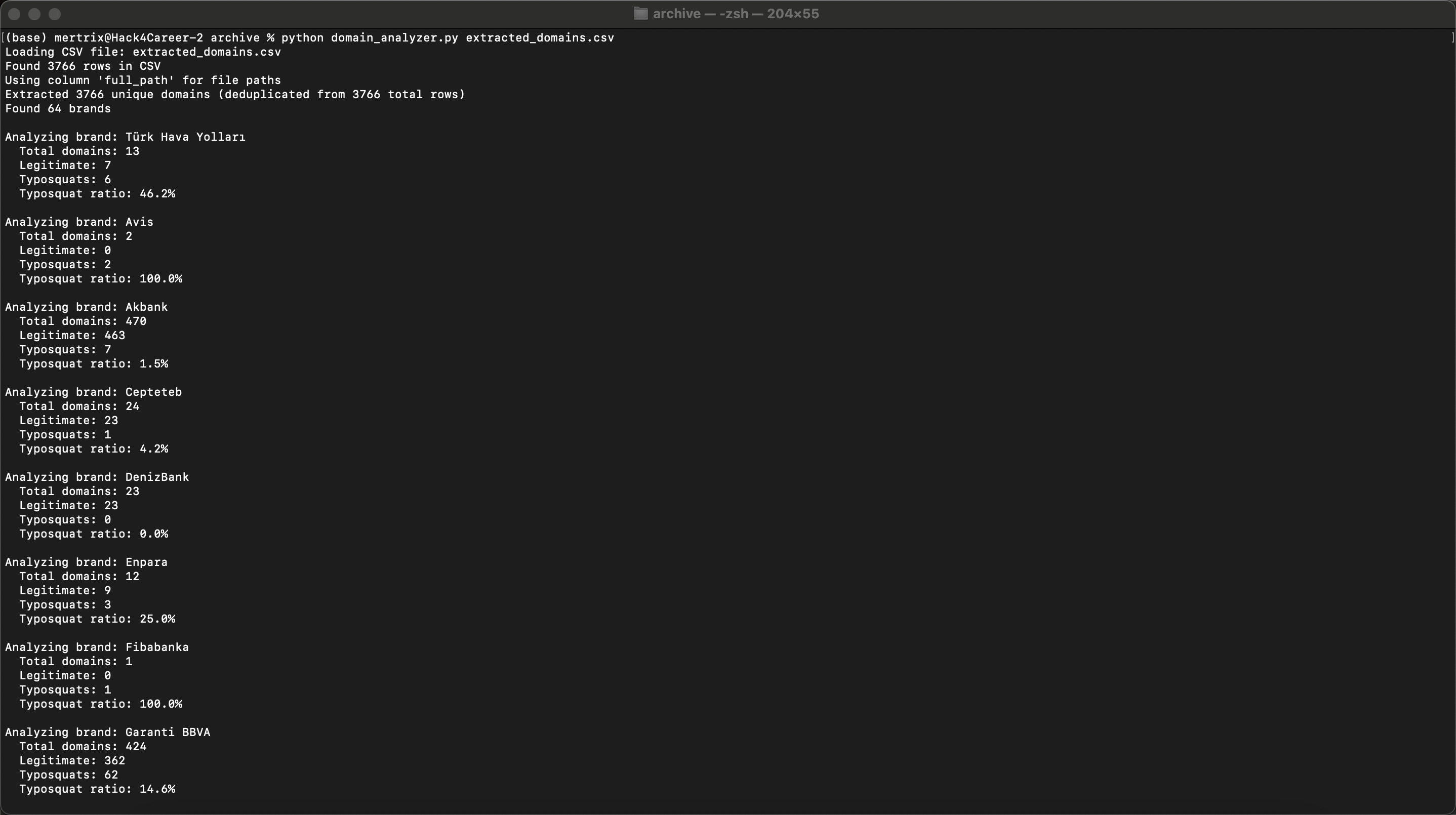

Claude performed a much more thorough typosquatting detection with a script consisting of 500 lines (domain_analyzer.py), while ChatGPT tried to solve the task with a simplified 75-line script and couldn’t deliver the level of insight I was expecting.

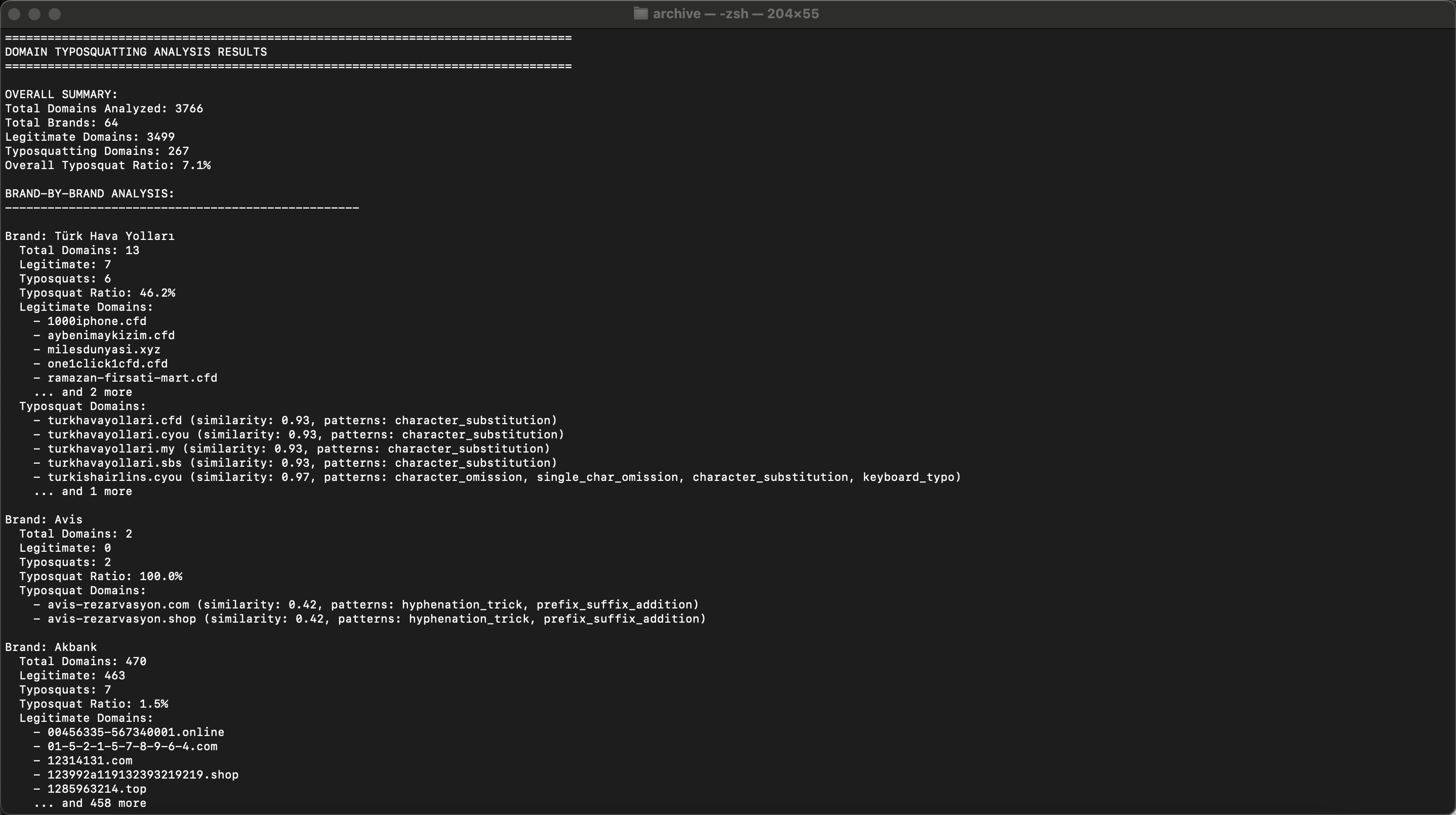

Looking at the results, although the typosquatting rate varied by corporate brand, in general (with some margin of error), it was found that 7.1% of the analyzed domains were typosquatting domains. (Categories like government, foundations, social aid, and unknowns were excluded.)

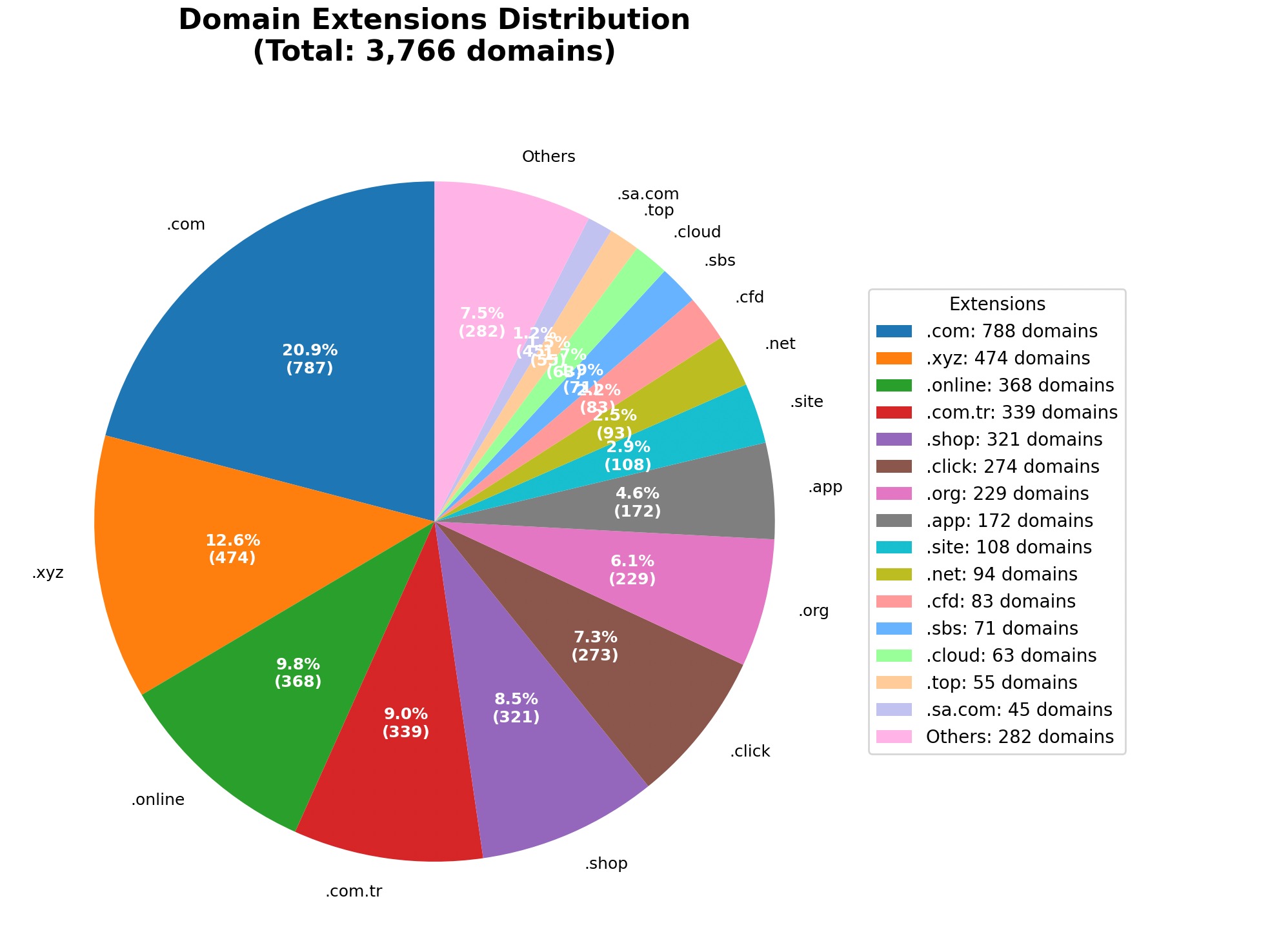

With another Python script (domain_extension_analyzer.py), this time excluding government, foundation, social aid, and unknown categories, I analyzed the domain extensions used in these phishing sites. It turned out that scammers most commonly used .com domains, followed by .xyz, and then .online.

The Phishing Market

Finally, to understand the market behind these phishing websites—which are sprouting up like mushrooms every day and created to ensnare hundreds of victims—I turned to the intelligence gathered from security research that had allowed me to trace and reach the scammers.

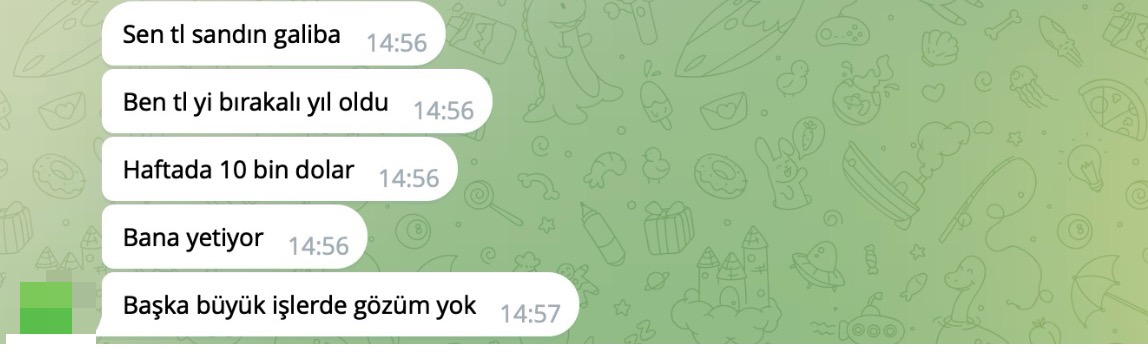

Through contact with these scammers and threat actors, I discovered that some were trying to sell these phishing websites for as low as 2,000 TL, while others priced them as high as 30,000 TL. Some, like in the example at the beginning of this article, did not hesitate to boast about their weekly earnings from these scams.

Conclusion

Looking at the previous sections, it was understood that scammers continued their phishing and fraud activities in 2025 without slowing down. The most important point that end users and citizens need to be careful about against scammers, who sometimes use advertising networks of social media platforms, is not to click on unknown links and always to check the domain name before entering personal information such as Turkish ID number (TCKN), passwords, or credit card details on a website. Especially if a domain has an extension like .xyz or .online, it should never be forgotten that there is a very high chance it is not the website of a well-known corporate brand.

Corporate brands, on the other hand, must definitely benefit from cyber threat intelligence services to detect phishing sites that scammers have registered and activated, in order to protect their customers.

Before concluding my writing, I can say with peace of mind that giving instructions to artificial intelligence on a specific topic without prior knowledge or expertise and expecting accurate, high-quality output is more of a dream than reality. For some time, we humans and experts will still be needed to manage AI and design workflows.

Hope to see you in the next article of the series.